联署发起人

赵立平、杨瑞馥、张发明、王军、马永慧等110余位热心肠智库专家,名单持续增加中,点击左下角按钮了解详情。

文章执笔 | 李丹宜、蓝灿辉

数据分析 | 高春辉

伦理支持 | 马永慧

肠道微生物群(Gut Microbiota,俗称肠道菌群,有时与Gut Microbiome——肠道微生物组混用,但二者内涵不同)是近年来科研圈里热度很高的话题。随着越来越多的研究进展和媒体报道,人们对肠道菌群研究也开始出现两极化的看法。

有些人觉得肠道菌群很“神奇”,认为什么疾病都跟它有关,甚至鼓吹肠道菌群“万能论”;也有些人戏称肠道菌群是“玄学”,甚至在生物医学研究领域中开始流传 “机制难寻,肠道菌群”的调侃。

应该说,这两种观点都是不够客观的,是不利于肠道菌群研究和转化应用发展的。因此我们今天特别通过数据分析和文献引用的方式,向关心肠道菌群的各界人士展示相关研究的客观事实,并提出我们的倡议。

事实1. 肠道菌群是主流的科学研究前沿

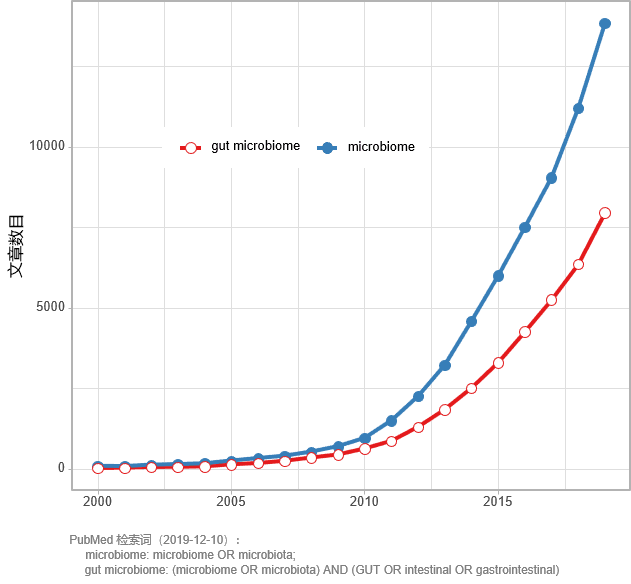

图1 PubMed中菌群和肠道菌群相关文献的增长趋势

通过搜索 PubMed 可以看出,在 2006 年以前,“菌群”和“肠道菌群”相关文献数量非常少(图1)。

而在过往13年,PubMed 中每年收录的“菌群”研究文献的数目,从2006年的 300 余篇增长到2018年的11000余篇,增长30多倍。截止到12月12日,2019年PubMed收录的相关文献已达13800余篇,预计全年会超过15000篇。

单独搜索“肠道菌群”相关研究文献,在过去13年占菌群相关研究数的比例基本保持在 60% 上下,数目从2006年的170余篇增加到2018年的6300余 篇,2019年预计会突破8500篇。

以上数据说明,肠道菌群已经走入科学研究的舞台中央。而在可预见的未来,相关文献还会快速增加,肠道菌群研究热潮还会持续。

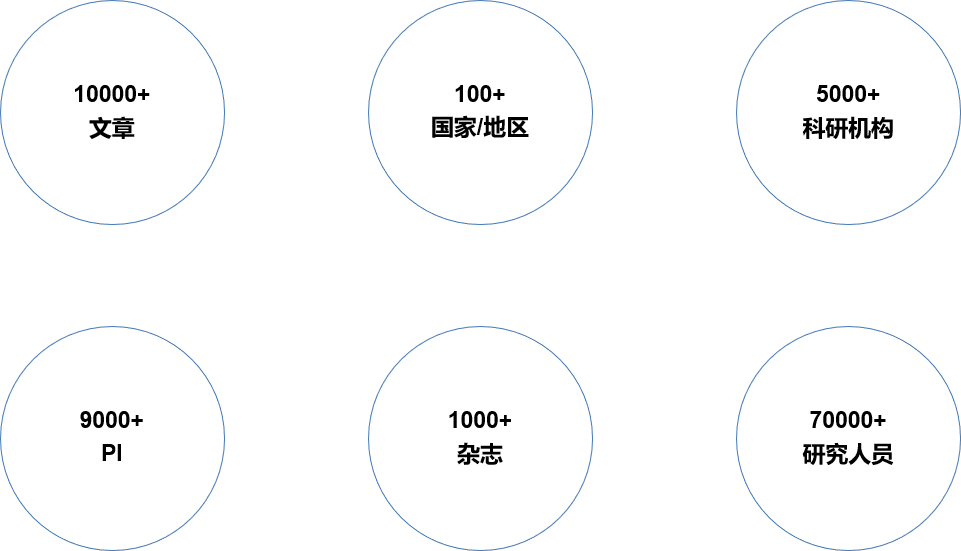

图2 《热心肠日报》收录文章基本数据

《热心肠日报》是热心肠生物技术研究院于2016年初创办,并持续解读肠道菌群相关高水平文献的内容平台,至2019年底将发布 1331 期。

以《热心肠日报》在近4年时间里收录并解读的10000余篇文献为例,这些研究成果涉及100多个国家和地区、5000 多个研究机构、9000多个课题组(以通讯作者计)以及70000 多位研究者(图2)。

这些数据从一个侧面反映出,在全世界范围内,肠道菌群相关研究确实受到科学家的广泛关注和参与。

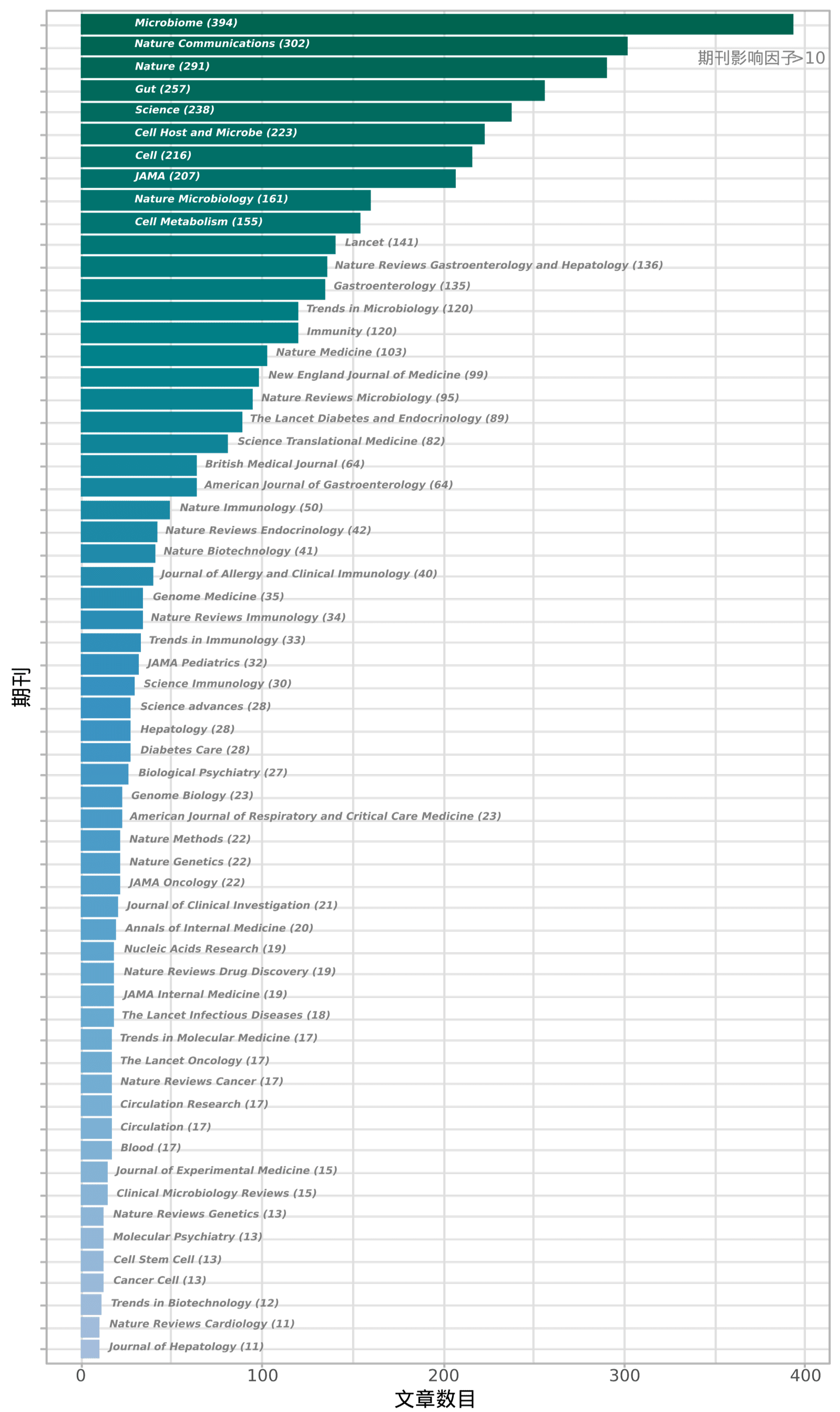

图3 《热心肠日报》中收录的部分高水平期刊论文数

《热心肠日报》收录的文献发表在1000 多本SCI期刊上,其中包括大量知名的高被引期刊(例如:2019年影响因子大于10)(图3)。

在生命科学领域最受关注的《自然》、《科学》、《细胞》、《美国医学会杂志》、《柳叶刀》和《新英格兰医学杂志》也都在持续发表肠道菌群相关的重要研究突破,它们被收录的文献数目分别高达291、238、216、207、141和99篇。

这些数字也体现出,主流学术界对肠道菌群相关科学探索的关注和认可。

而在肠道菌群研究兴起的背后,是前沿生物学研究技术的快速发展1,2。无菌动物模型3、二代测序技术4,以及宏基因组学、宏转录组学、代谢组学5,6和培养组学7等多组学技术及分析方法的发展和应用,不仅使得研究者能解析肠道菌群的组成和结构,还能从不同交叉学科的角度,对菌群的功能及其与健康和疾病的关联进行研究和验证。

事实2. 全球都在加码肠道菌群研究

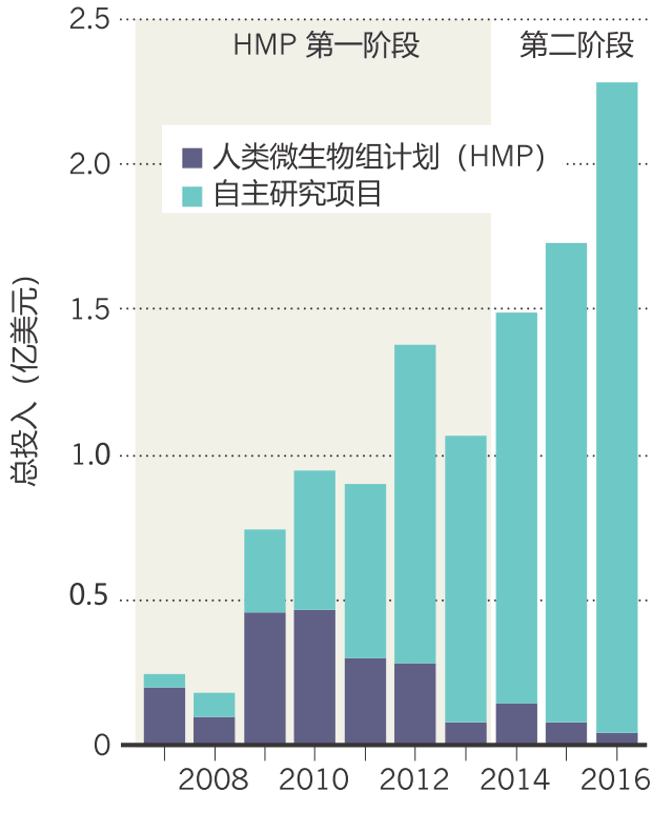

图4 2007-2016年美国菌群研究经费8

之所以肠道菌群相关研究自 2006 年起开始突飞猛进,既与科学界对菌群功能的认识逐渐深入有关,也和国家的战略支持密不可分。

这其中以美国国立卫生研究院(NIH)的人类微生物组计划(HMP)最为人熟知。在2007-2016年间,NIH在人类微生物组计划中累计投入了2.15亿美元8(图4)。2012-2016年,NIH在HMP之外又投入了7.28亿美元用于人类微生物组领域的其它研究9。

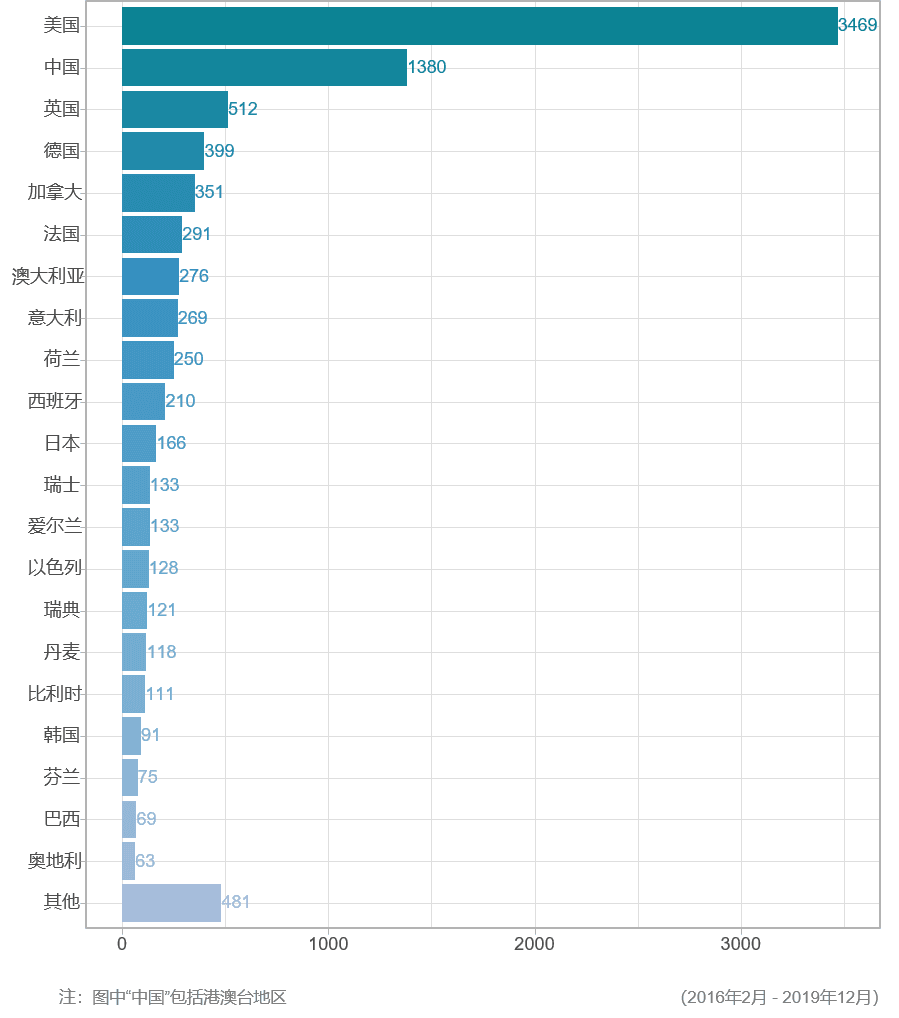

图5 按国家统计《热心肠日报》中收录的论文数

高额投入实现了高产,在《热心肠日报》近四年收录的文献中,有超过1/3来自于美国的研究机构(图5)。不过中国(包括港澳台地区)、英国、德国、加拿大、法国等其他国家和地区也在持续加大投入。据估算,全球在过去十年对菌群相关研究的资金投入已超过17亿美元8。

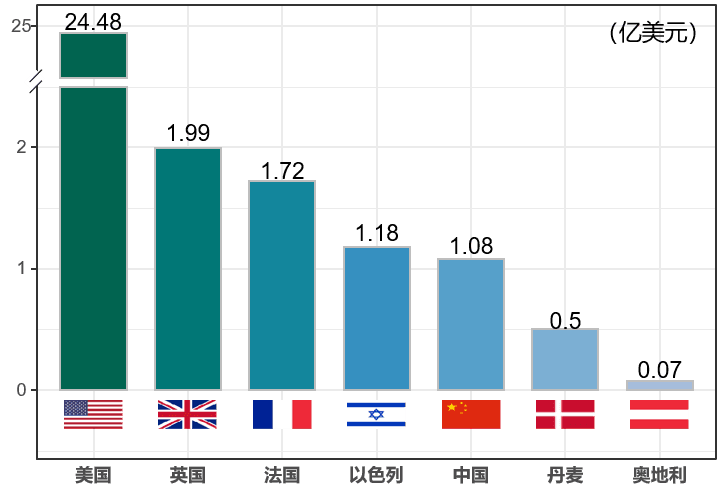

图6 不同国家肠道菌群相关公司融资额

与此同时,肠道菌群相关的产业转化也在持续发展,菌群及相关生物技术公司的成立如雨后春笋,资金投入也越来越大。截止到2019年,全球有超过30亿美元投入到肠道菌群相关创新公司(图6)。与基础研究情况类似,美国以超过24亿美元投资一马当先,其他国家正迎头追赶。

事实3. 肠道菌群与疾病和健康关系密切

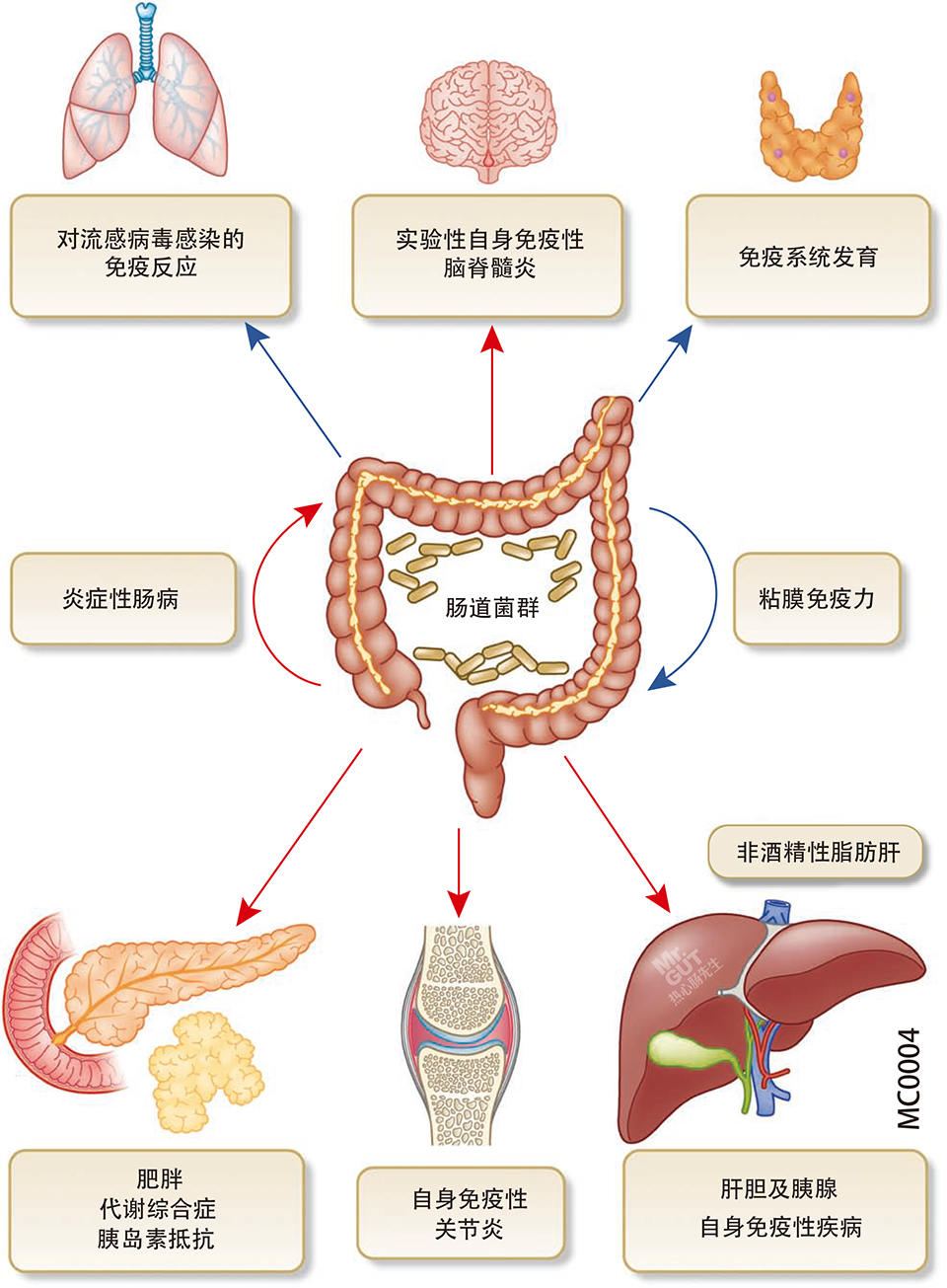

图7 肠道菌群与其它器官互作,影响免疫健康10

肠道在健康中的枢纽性作用,是肠道菌群参与宿主生理过程甚至影响人体健康与疾病的基础10(图7)。除了负责营养的消化、吸收和代谢,肠道还是重要的免疫和内分泌器官,而且,肠道还被称为“第二大脑”,有着丰富的肠神经系统,并通过迷走神经与大脑沟通11-16。

近年来,肠道菌群研究已经从描述性和关联性向因果性和机制性转变1,17。2006年Jeffrey Gordon团队在Nature发表研究,通过对小鼠进行粪菌移植实验,首次表明肠道菌群可影响和传递宿主的肥胖表型18。

之后越来越多的研究表明,肠道菌群可被视为身体中的 “微生物器官”19,20,通过菌群的自身成分、代谢物和衍生物21,22,以及致病共生菌移位等机制23,24,参与调控宿主的代谢25、免疫26、内分泌27,28、神经29等多方面的局部和全身性生理过程,从而影响发生肥胖30,31、糖尿病32、脂肪肝33、心血管疾病34、自身免疫和炎症性疾病35、精神神经疾病36和癌症37-39等疾病的风险40-43。

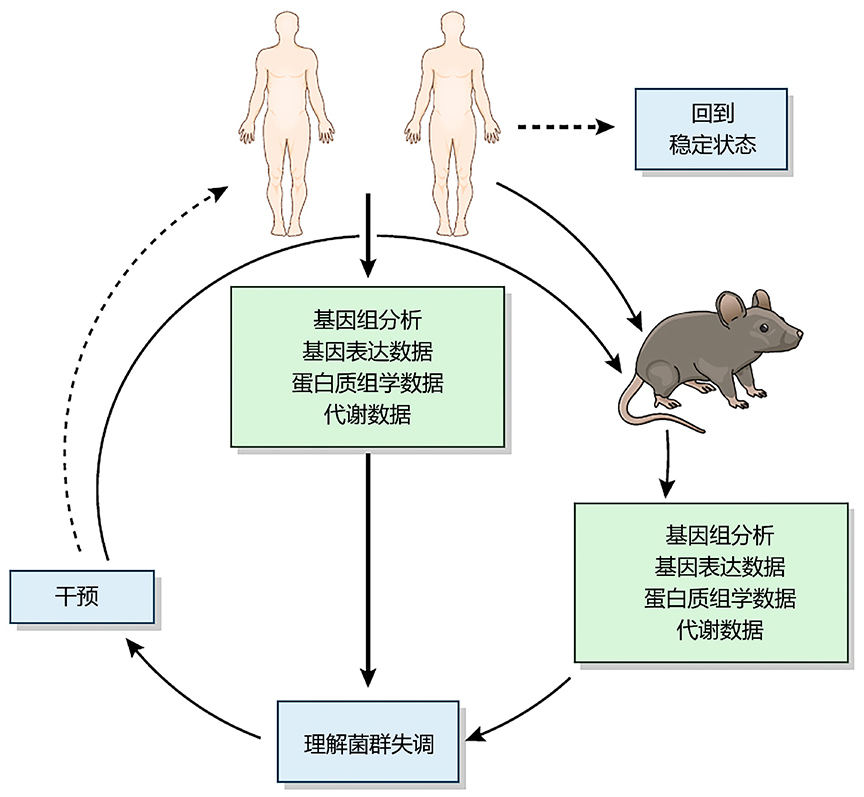

图8 菌群疗法研发思路1

肠道菌群研究不仅有助于更全面的揭示疾病的发生发展过程和机制,还促进了新型诊断和干预疗法的研发1(图8)。

肠道菌群可用于结直肠癌的无创筛查,能提高现有筛查方法的准确性44。用粪菌移植恢复肠道微生态可有效治疗复发性艰难梭菌感染,在治疗炎症性肠病方面也有效果45。膳食纤维干预可通过改变肠道菌群来改善糖尿病46,用菌群导向的饮食干预方法也可在一定程度上改善儿童营养不良47。

肠道菌群还是发展个性化医疗的重要因素。比如,基于菌群等指标的算法可用于预测个体的餐后血糖反应48;靶向特定致病共生菌,也是治疗相应疾病的潜在方法49,50。

另外,肠道菌群还能通过参与药物代谢、影响宿主免疫应答等机制,对药物和疗法的效果产生影响51-53;过于“干净”的实验动物,也被证实并非是药物研发的最佳模型54。

4. 肠道菌群异常只是疾病因素之一

图9 影响II型糖尿病和肥胖的诸多后天因素55

尽管大量研究证实肠道菌群对人体健康有重要意义,但除此以外,遗传、环境、生活方式等,对健康与疾病也都有巨大影响55-58。在一些情况下,肠道菌群只是连接这些因素与疾病的中间一环,而非最本质的因素。

比如,与肠道菌群密切相关的糖尿病和肥胖等代谢疾病,尽管有观点认为菌群或许是其中最重要的可变因素59,然而,究竟菌群对于这些疾病的贡献能占多大比例,尚无定论。这些疾病的发生更可能是一个综合性结果,遗传易感性、饮食、运动、发育、睡眠、药物使用等多种因素,都可能影响疾病风险(图9)。

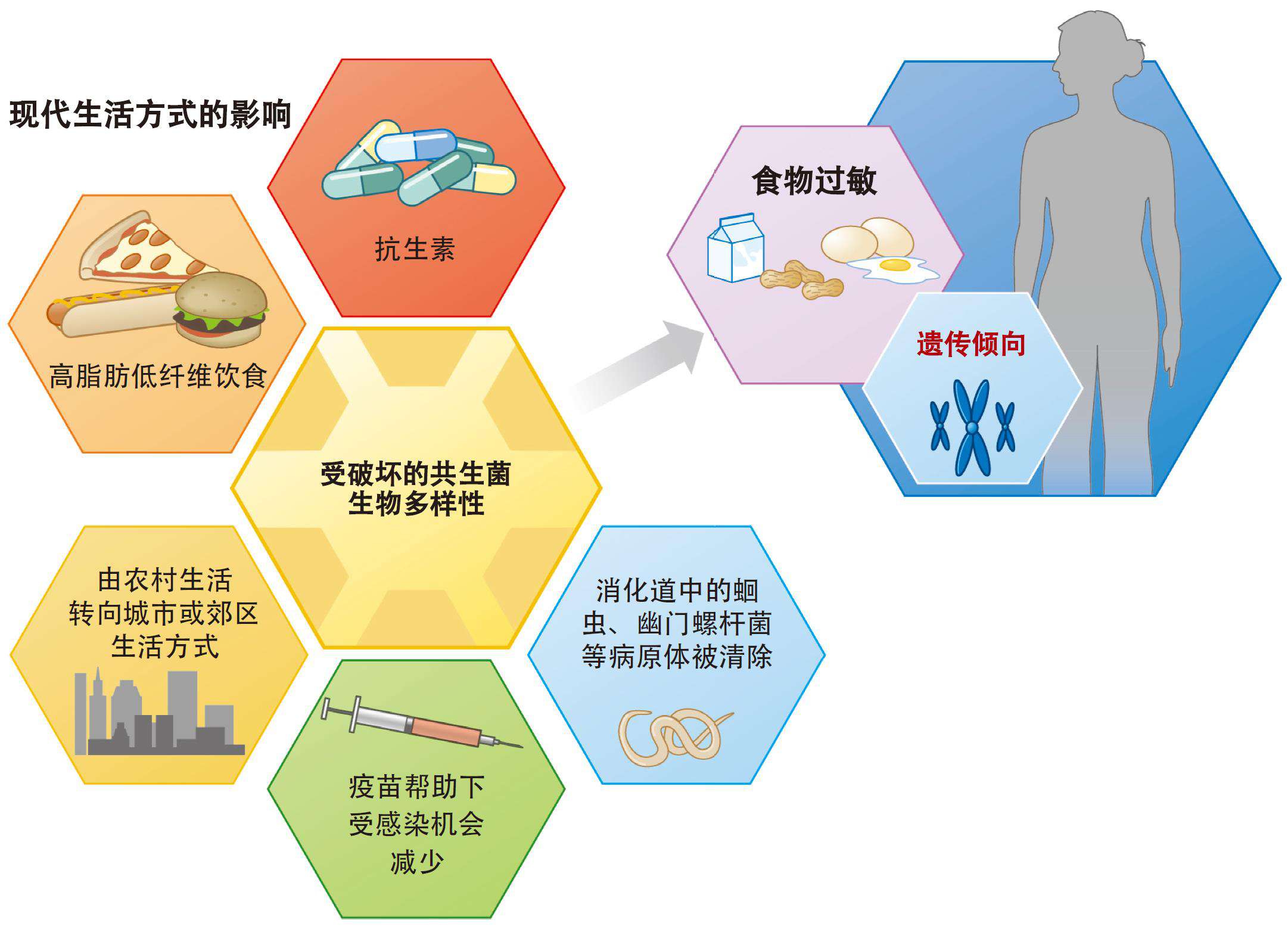

图10 众多现代化和工业化生活方式与菌群共同促进食物过敏60

再比如,发病率持续上升的食物过敏也与肠道菌群有关,益生菌、益生元和粪菌移植等肠道菌群调节方法,似乎也有改善效果61。

然而过敏性疾病的发生,同样也是综合性因素共同作用的结果60(图10),在遗传因素之外,剖腹产、早产、抗生素、环境污染、生命早期病原体感染、吸烟酗酒等孕产妇因素等都可能促进食物过敏的发生62-64,而相关应对策略也需要综合性考虑65。

我们在面对腹泻66、炎症性肠病67、肠易激综合征68、心血管疾病69、自闭症70、阿尔兹海默症71、帕金森病72等与肠道菌群的关系或远或近的疾病时,都需要特别认识到肠道菌群只是疾病的一个因素,不能随意拔高菌群的重要性。

事实5. 肠道菌群研究仍处于早期阶段

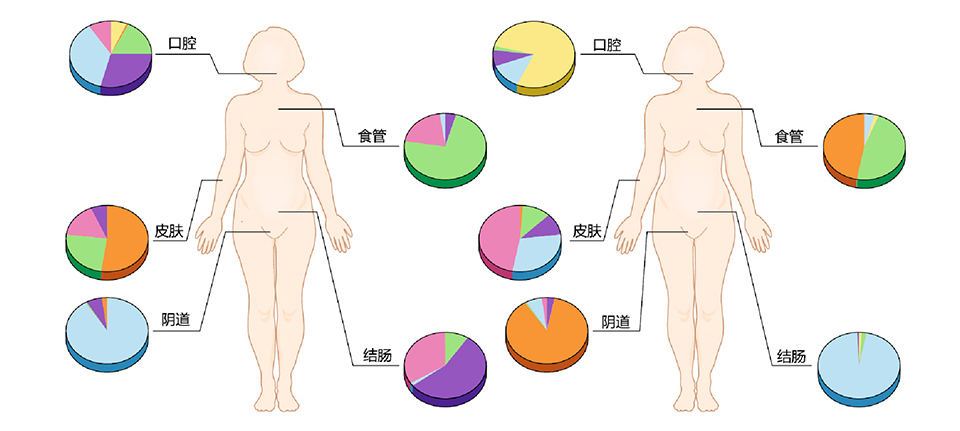

图11 高度个体化的人类菌群1

目前我们对肠道菌群的了解可能仍然只是冰山一角,这个领域还存在很多局限、未知和争议。

人与人之间的肠道菌群是高度个体化的1(图11),且短时间内同一个人的菌群也高度动态化,健康的菌群究竟如何定义?目前还没有人可以准确回答,而这种“基线缺失”,也阻碍了一些转化和干预的实施73。

在细菌之外,噬菌体74、真菌75、古菌76等其它肠道微生物对健康和疾病的影响几何?目前相关研究仍处于起步阶段。对于菌群中大量未知和不可培养的微生物,怎样研究它们的功能和作用?尽管宏基因组等技术可辅助分析,培养组学也取得了一定的进步,但相关研究仍待加强77。

图12 治疗苯丙酮尿症的工程菌临床试验失败

动物研究中的结论,在人体中也依然成立吗?美国Synlogic公司意图用于治疗苯丙酮尿症的工程菌在小鼠中有效78,人体临床试验却以失败告终(图12,点击图片可阅读详情),提醒我们不能简单把动物研究结果推导到人身上。

如何解决菌群研究的标准化和可重复性问题?这样的根本性问题还需要全球科学家携手,合作建设全球通行的标准化方法和更加开放共享的数据库等才能更进一步79-82。

益生元、益生菌以及粪菌移植等菌群干预疗法的长期安全性是怎样的?近年的多项研究提示我们,诸多看起来安全的干预方法,其实存在潜在风险83-86。如何实现对菌群的精准操纵?基于肠道菌群的个体化营养研究和转化87,88备受关注,但仍欠缺大样本量人群的干预和追踪结果。

应该说,肠道菌群研究仍处于早期阶段,未来还需要更深入的研究和更好的方法,来明确肠道菌群在人体健康与疾病中的作用和机制,以及相关干预方法的有效性和可行性。

事实6. 肠道菌群领域存在乱象和利益冲突

在一些研究者的不当自我宣传和包装、一些媒体的夸大宣传和商家的不良商业炒作下,肠道菌群和一些衍生产品,被赋予了“包治百病”的外壳;甚至在一些激进的科研人员眼中,肠道菌群也快成为“无所不能”的代言词了。这些比较极端的观点,无疑是不利于肠道菌群产学研的健康发展的。

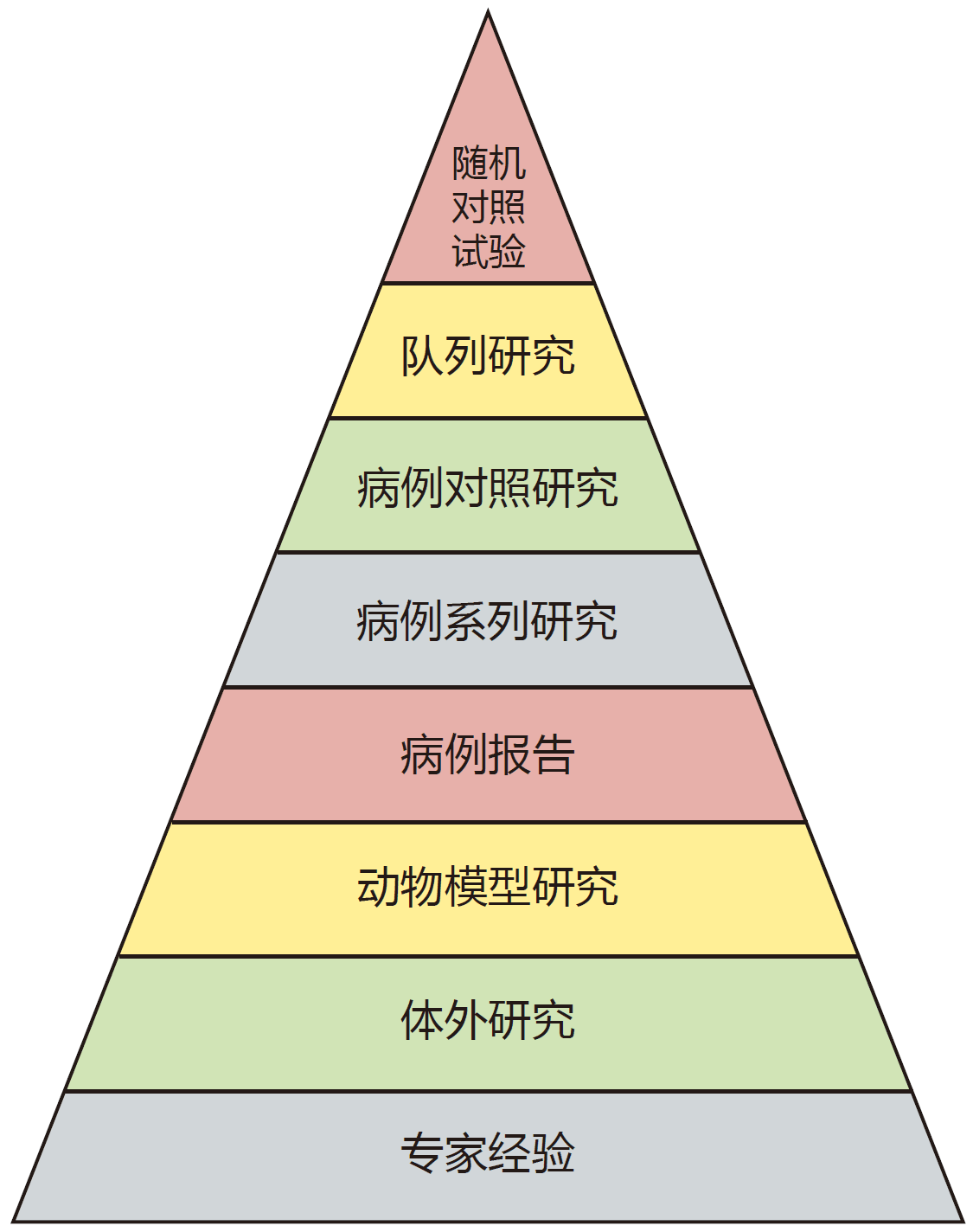

图13 临床随机对照试验处于现有证据等级顶端89

临床随机对照试验(RCT)是评价药物安全性和有效性的金标准89,90(图13),也常用于评估肠道菌群相关干预方法。但是,在现实世界中,用RCT对益生菌和益生元等进行功效评估,可能存在个体差异、干预时间过短等局限性91,事实上,相关功能证据既有限也确实难以研究92。

在此背景下,夸大益生菌的作用,将肠道菌群的功能偷换概念为特定产品的功能,滥用相关性研究结果,忽视菌群的复杂度而过于简化的设计检测和干预产品等现象较为常见的93。

而且,在商业推广中,存在向免疫低下人群等无差别推荐益生菌的情况,而这种做法是有潜在安全风险的94。事实上, ICU患者86、住院老年人95等特殊人群使用益生菌,可能增加菌血症风险;甚至在极端情况下,免疫力弱的老年人长年食用酸奶,都可能造成肝脓肿和菌血症96。

图14 “菌群失调”或许是个伪命题

在“健康的菌群究竟长啥样”这一根本问题还未得到有效解答的当下, “肠道菌群失调/紊乱”等名词被滥用(图14,点击图片可阅读详情),成为诱导消费者和患者购买产品的概念97。

此外,研究中的商业利益冲突,也是需要警惕的问题。比如,食品企业主导的营养学研究98,甚至公共卫生研究机构99、专业学会或协会100、指南制定者101,都可能受到利益的左右102。营养学研究和荟萃分析也可能被摆布,用来掩盖一些产品的负面问题103。

在这样的背景下,一些婴幼儿奶粉产品宣称的“促进认知发展”和“保障肠道健康”的功效,实际上可能缺乏足够的科学证据104。而如何规范类似乱象,是让包括美国FDA在内的全世界监管机构头疼的问题105。

事实7. 肠道菌群科学共同体有自净机制

很多专家学者早已意识到,肠道菌群领域过热可能引发泡沫问题,加强行业自律的呼声也越来越高,不少人通过科学杂志提出很多促进科学共同体自净的建议。

首先,很多学者都呼吁,要对菌群研究保持严谨和质疑精神93,106。比如,描述结果时要精准、详实,避免对非因果性研究和动物实验的结果进行过度解读;在加强积累因果关系证据的同时,菌群研究还应深入到菌株和基因水平,着力探究发挥作用的确切机制107,这一点对于益生菌领域尤其重要108。菌群研究中的标准化程序和方法,也是科学家们在着重解决的问题109。

肠道菌群干预手段层出,如何进行有效监管成为了新课题110。针对有潜在风险的益生菌94、粪菌移植111,112等菌群干预手段的研究和实施,以及以菌群健康为导向的新型食物(菌群靶向性食物)113,有学者也提出一系列监管建议。

肠道菌群研究和转化需要有效规避风险与安全问题,也需要公众的理解、支持和参与114,115,遵从生命伦理学基本原则成为众多学者的共识116,117。

特别的,在复杂而多面的利益冲突问题上,有学者也专门提出并非无解决之道118。同时先后有人呼吁健康政策制定不应受食品工业利益影响119,科研工作者应主动全面地公开利益冲突120,医生应该向患者公开相关利益冲突121。

可以说,在研究设计和执行、监管方式、生命伦理等方方面面,肠道菌群科学共同体已经建立起非常立体的自净机制。

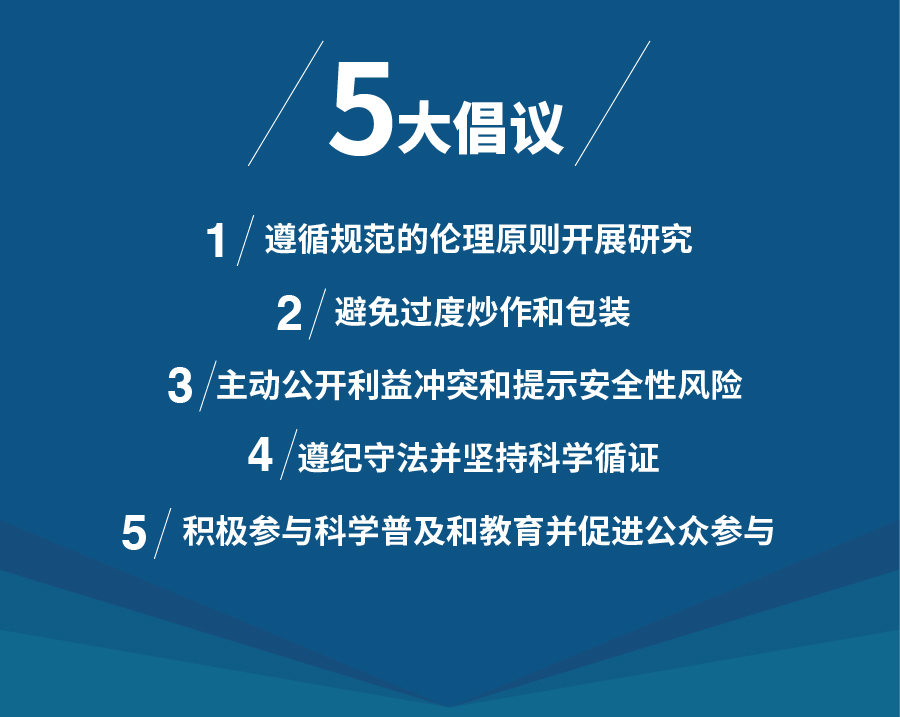

5大倡议

基于以上关于肠道菌群研究的7大事实,我们特别针对相关领域的基础研究者、临床医生和产业化专业人士提出5点倡议:

我们倡议肠道菌群相关科研活动须接受必要的伦理审查和同行评议。

研究者应学习、践行并敬畏生命伦理学,坚守科学精神、科学文化和科研伦理;在求真务实、理性批判的基础上,努力做到勇于创新、责任担当;及时调整自身与合作者(包括其他科研人员、资助者、受试者、社会公众/消费者)、与物(包括试验动物、生态环境等)之间的关系,并承担社会责任。

我们倡议基础研究者、临床医生、产业界和媒体人士都要避免针对肠道菌群的过度炒作和自我包装,并积极参与全领域的自律和自净工作。

研究者应避免单纯利用单位、职务背书来塑造个人影响力,抑制个人营销冲动,在宣传个人和团队研究成果时避免夸大或浮夸。在科研、产业和媒体宣传工作中,避免肠道菌群“万能论”和“无用论”;反对投机主义、搞标题党和蹭热度;反对将肠道菌群研究庸俗化、伪科学化,包括反对滥用“肠道菌群”概念到不相干领域,或承诺不切实际的效果等。

我们倡议具有利益冲突的研究者在论文发表、学术演讲、媒体宣传等各种场合主动公开利益冲突,同时如相关产品和服务存在潜在安全性风险,应主动向消费者或患者提示。

在研究和转化的风险界定、评估、风险管理与损害管控等工作中,应强化信息透明与开诚布公。研究者主动公开利益冲突,不仅有利于个人,也会有利于产品或服务的品牌积累和传播。主动提示安全性风险,同样会增加个人、产品或服务的品牌信任度,也切实避免给消费者或患者带来风险,并因此降低产业化的系统性风险。

我们倡议在产业化过程中要严格遵守国家法律法规并坚持科学循证。

特定产品或服务的功能、功效、疗效声称,必须符合国家有关法律法规规定,绝不可突破法律底线。产品或服务的相关功能、功效、疗效等宣传应建立在高等级证据的基础上,应积累自身的临床随机对照试验(RCT)证据。不应过度解读细胞、动物实验结果,但要重视相关实验提示的副作用、过犹不及等风险。

我们倡议专业人士积极参与面向公众的科学普及、传播和教育活动,同时有意识的吸纳公众意见,鼓励公众平等参与科学研究。

肠道菌群研究日新月异,知识更新和积累速度飞快,但乱象丛生,令人无所适从,同时相关领域的发展也日益受商业化支配, 可能损害到公众利益。因此迫切需要更多权威、主流的一线专业人士参与到面向大众的科普活动中。在日常传播工作中,专业人士可系统化普及肠道菌群相关知识;有重大事件发生时,应及时响应公众关切,做到正本清源。

参考文献

(滑动下方文字查看)

1. Gilbert JA, Blaser MJ, Caporaso JG, Jansson JK, Lynch SV, Knight R. Current understanding of the human microbiome. Nat Med. 2018;24(4):392-400.

2. Gilbert JA, Quinn RA, Debelius J, et al. Microbiome-wide association studies link dynamic microbial consortia to disease. Nature. 2016;535(7610):94-103.

3. Uzbay T. Germ-free animal experiments in the gut microbiota studies. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2019;49:6-10.

4. Shendure J, Balasubramanian S, Church GM, et al. DNA sequencing at 40: past, present and future. Nature. 2017;550(7676):345-353.

5. Quince C, Walker AW, Simpson JT, Loman NJ, Segata N. Shotgun metagenomics, from sampling to analysis. Nat Biotechnol. 2017;35(9):833-844.

6. Zhang X, Li L, Butcher J, Stintzi A, Figeys D. Advancing functional and translational microbiome research using meta-omics approaches. Microbiome. 2019;7(1):154.

7. Lagier JC, Dubourg G, Million M, et al. Culturing the human microbiota and culturomics. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2018;16:540-550.

8. Proctor L. Priorities for the next 10 years of human microbiome research. Nature. 2019;569(7758):623-625.

9. Team NHMPA. A review of 10years of human microbiome research activities at the US National Institutes of Health, Fiscal Years 2007-2016. Microbiome. 2019;7(1):31.

10. Goldszmid RS, Trinchieri G. The price of immunity. Nat Immunol. 2012;13(10):932-938.

11. Weiner HL, da Cunha AP, Quintana F, Wu H. Oral tolerance. Immunol Rev. 2011;241(1):241-259.

12. Rehfeld JF. The new biology of gastrointestinal hormones. Physiological reviews. 1998;78(4):1087-1108.

13. Gribble FM, Reimann F. Function and mechanisms of enteroendocrine cells and gut hormones in metabolism. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2019;15(4):226-237.

14. Yoo BB, Mazmanian SK. The Enteric Network: Interactions between the Immune and Nervous Systems of the Gut. Immunity. 2017;46(6):910-926.

15. Mayer EA. Gut feelings: the emerging biology of gut-brain communication. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12(8):453-466.

16. Avetisyan M, Schill EM, Heuckeroth RO. Building a second brain in the bowel. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(3):899-907.

17. Schmidt TSB, Raes J, Bork P. The Human Gut Microbiome: From Association to Modulation. Cell. 2018;172(6):1198-1215.

18. Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Mahowald MA, Magrini V, Mardis ER, Gordon JI. An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature. 2006;444(7122):1027-1031.

19. O'Hara AM, Shanahan F. The gut flora as a forgotten organ. EMBO reports. 2006;7(7):688-693.

20. Byndloss MX, Bäumler AJ. The germ-organ theory of non-communicable diseases. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2018;16(2):103-110.

21. Schroeder BO, Bäckhed F. Signals from the gut microbiota to distant organs in physiology and disease. Nature medicine. 2016;22(10):1079-1089.

22. Dalile B, Van Oudenhove L, Vervliet B, Verbeke K. The role of short-chain fatty acids in microbiota-gut-brain communication. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16(8):461-478.

23. Manfredo Vieira S, Hiltensperger M, Kumar V, et al. Translocation of a gut pathobiont drives autoimmunity in mice and humans. Science. 2018;359(6380):1156-1161.

24. Meisel M, Hinterleitner R, Pacis A, et al. Microbial signals drive pre-leukaemic myeloproliferation in a Tet2-deficient host. Nature. 2018;557(7706):580-584.

25. Tilg H, Zmora N, Adolph TE, Elinav E. The intestinal microbiota fuelling metabolic inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2019.

26. Belkaid Y, Harrison OJ. Homeostatic Immunity and the Microbiota. Immunity. 2017;46(4):562-576.

27. Rooks MG, Garrett WS. Gut microbiota, metabolites and host immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16(6):341-352.

28. Rastelli M, Cani PD, Knauf C. The Gut Microbiome Influences Host Endocrine Functions. Endocrine reviews. 2019;40(5):1271-1284.

29. Sharon G, Sampson TR, Geschwind DH, Mazmanian SK. The Central Nervous System and the Gut Microbiome. Cell. 2016;167(4):915-932.

30. Le Chatelier E, Nielsen T, Qin J, et al. Richness of human gut microbiome correlates with metabolic markers. Nature. 2013;500(7464):541-546.

31. Ridaura VK, Faith JJ, Rey FE, et al. Gut microbiota from twins discordant for obesity modulate metabolism in mice. Science. 2013;341(6150):1241214.

32. Qin J, Li Y, Cai Z, et al. A metagenome-wide association study of gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2012;490(7418):55-60.

33. Canfora EE, Meex RCR, Venema K, Blaak EE. Gut microbial metabolites in obesity, NAFLD and T2DM. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2019;15(5):261-273.

34. Schiattarella GG, Sannino A, Toscano E, et al. Gut microbe-generated metabolite trimethylamine-N-oxide as cardiovascular risk biomarker: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(39):2948-2956.

35. Clemente JC, Manasson J, Scher JU. The role of the gut microbiome in systemic inflammatory disease. BMJ. 2018;360:j5145.

36. Cryan JF, O'Riordan KJ, Sandhu K, Peterson V, Dinan TG. The gut microbiome in neurological disorders. The Lancet Neurology. 2019:S1474-4422(1419)30356-30354.

37. Garrett WS. Cancer and the microbiota. Science. 2015;348(6230):80-86.

38. Vitiello GA, Cohen DJ, Miller G. Harnessing the Microbiome for Pancreatic Cancer Immunotherapy. Trends Cancer. 2019;5(11):670-676.

39. Yu LX, Schwabe RF. The gut microbiome and liver cancer: mechanisms and clinical translation. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14(9):527-539.

40. Sekirov I, Russell SL, Antunes LC, Finlay BB. Gut microbiota in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2010;90(3):859-904.

41. Clemente JC, Ursell LK, Parfrey LW, Knight R. The impact of the gut microbiota on human health: an integrative view. Cell. 2012;148(6):1258-1270.

42. Nicholson JK, Holmes E, Kinross J, et al. Host-gut microbiota metabolic interactions. Science. 2012;336(6086):1262-1267.

43. Lynch SV, Pedersen O. The Human Intestinal Microbiome in Health and Disease. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(24):2369-2379.

44. Wong SH, Yu J. Gut microbiota in colorectal cancer: mechanisms of action and clinical applications. Nature reviews Gastroenterology & hepatology. 2019;16(11):690-704.

45. Vaughn BP, Rank KM, Khoruts A. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation: Current Status in Treatment of GI and Liver Disease. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2019;17(2):353-361.

46. Zhao L, Zhang F, Ding X, et al. Gut bacteria selectively promoted by dietary fibers alleviate type 2 diabetes. Science (New York, NY). 2018;359(6380):1151-1156.

47. Gehrig JL, Venkatesh S, Chang H-W, et al. Effects of microbiota-directed foods in gnotobiotic animals and undernourished children. Science (New York, NY). 2019;365(6449):eaau4732.

48. Zeevi D, Korem T, Zmora N, et al. Personalized Nutrition by Prediction of Glycemic Responses. Cell. 2015;163(5):1079-1094.

49. Yuan J, Chen C, Cui J, et al. Fatty Liver Disease Caused by High-Alcohol-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Cell Metab. 2019;30(4):675-688.e677.

50. Duan Y, Llorente C, Lang S, et al. Bacteriophage targeting of gut bacterium attenuates alcoholic liver disease. Nature. 2019;575(7783):505-511.

51. Zimmermann M, Zimmermann-Kogadeeva M, Wegmann R, Goodman AL. Separating host and microbiome contributions to drug pharmacokinetics and toxicity. Science. 2019;363(6427).

52. Zimmermann M, Zimmermann-Kogadeeva M, Wegmann R, Goodman AL. Mapping human microbiome drug metabolism by gut bacteria and their genes. Nature. 2019;570(7762):462-467.

53. Skelly AN, Sato Y, Kearney S, Honda K. Mining the microbiota for microbial and metabolite-based immunotherapies. Nat Rev Immunol. 2019;19(5):305-323.

54. Rosshart SP, Herz J, Vassallo BG, et al. Laboratory mice born to wild mice have natural microbiota and model human immune responses. Science. 2019;365(6452).

55. Franks PW, McCarthy MI. Exposing the exposures responsible for type 2 diabetes and obesity. Science (New York, NY). 2016;354(6308):69-73.

56. Hall AB, Tolonen AC, Xavier RJ. Human genetic variation and the gut microbiome in disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2017;18(11):690-699.

57. Gentile CL, Weir TL. The gut microbiota at the intersection of diet and human health. Science. 2018;362(6416):776-780.

58. Scott AJ, Alexander JL, Merrifield CA, et al. International Cancer Microbiome Consortium consensus statement on the role of the human microbiome in carcinogenesis. Gut. 2019;68(9):1624-1632.

59. Komaroff AL. The Microbiome and Risk for Obesity and Diabetes. JAMA. 2017;317(4):355-356.

60. Iweala OI, Nagler CR. The Microbiome and Food Allergy. Annu Rev Immunol. 2019;37:377-403.

61. Bunyavanich S. Food allergy: could the gut microbiota hold the key? Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16(4):201-202.

62. Levin ME, Botha M, Basera W, et al. Environmental factors associated with allergy in urban and rural children from the South AFrican Food Allergy (SAFFA) cohort. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019.

63. Reynolds LA, Finlay BB. Early life factors that affect allergy development. Nat Rev Immunol. 2017;17(8):518-528.

64. Mitselou N, Hallberg J, Stephansson O, Almqvist C, Melén E, Ludvigsson JF. Cesarean delivery, preterm birth, and risk of food allergy: Nationwide Swedish cohort study of more than 1 million children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;142(5):1510-1514.e1512.

65. Tordesillas L, Berin MC, Sampson HA. Immunology of Food Allergy. Immunity. 2017;47(1):32-50.

66. Singh P, Mitsuhashi S, Ballou S, et al. Demographic and Dietary Associations of Chronic Diarrhea in a Representative Sample of Adults in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(4):593-600.

67. Piovani D, Danese S, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Nikolopoulos GK, Lytras T, Bonovas S. Environmental Risk Factors for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: An Umbrella Review of Meta-analyses. Gastroenterology. 2019;157(3):647-659.e644.

68. Ford AC, Lacy BE, Talley NJ. Irritable Bowel Syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(26):2566-2578.

69. Miller V, Mente A, Dehghan M, et al. Fruit, vegetable, and legume intake, and cardiovascular disease and deaths in 18 countries (PURE): a prospective cohort study. Lancet (London, England). 2017;390(10107):2037-2049.

70. Bai D, Yip BHK, Windham GC, et al. Association of Genetic and Environmental Factors With Autism in a 5-Country Cohort. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019.

71. Kivipelto M, Mangialasche F, Ngandu T. Lifestyle interventions to prevent cognitive impairment, dementia and Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2018;14(11):653-666.

72. Ascherio A, Schwarzschild MA. The epidemiology of Parkinson's disease: risk factors and prevention. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15(12):1257-1272.

73. Lloyd-Price J, Abu-Ali G, Huttenhower C. The healthy human microbiome. Genome Med. 2016;8(1):51.

74. Shkoporov AN, Hill C. Bacteriophages of the Human Gut: The "Known Unknown" of the Microbiome. Cell Host Microbe. 2019;25(2):195-209.

75. Richard ML, Sokol H. The gut mycobiota: insights into analysis, environmental interactions and role in gastrointestinal diseases. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16(6):331-345.

76. Pennisi E. Survey of archaea in the body reveals other microbial guests. Science. 2017;358(6366):983.

77. Nayfach S, Shi ZJ, Seshadri R, Pollard KS, Kyrpides NC. New insights from uncultivated genomes of the global human gut microbiome. Nature. 2019;568(7753):505-510.

78. Isabella VM, Ha BN, Castillo MJ, et al. Development of a synthetic live bacterial therapeutic for the human metabolic disease phenylketonuria. Nat Biotechnol. 2018;36(9):857-864.

79. Servick K. Of mice and microbes. Science. 2016;353(6301):741-743.

80. Poussin C, Sierro N, Boué S, et al. Interrogating the microbiome: experimental and computational considerations in support of study reproducibility. Drug Discov Today. 2018;23(9):1644-1657.

81. Schloss PD. Identifying and Overcoming Threats to Reproducibility, Replicability, Robustness, and Generalizability in Microbiome Research. MBio. 2018;9(3).

82. Costea PI, Zeller G, Sunagawa S, et al. Towards standards for human fecal sample processing in metagenomic studies. Nat Biotechnol. 2017;35(11):1069-1076.

83. Singh V, Yeoh BS, Chassaing B, et al. Dysregulated Microbial Fermentation of Soluble Fiber Induces Cholestatic Liver Cancer. Cell. 2018;175(3):679-694.e622.

84. Suez J, Zmora N, Zilberman-Schapira G, et al. Post-Antibiotic Gut Mucosal Microbiome Reconstitution Is Impaired by Probiotics and Improved by Autologous FMT. Cell. 2018;174(6):1406-1423.e1416.

85. DeFilipp Z, Bloom PP, Torres Soto M, et al. Drug-Resistant E. coli Bacteremia Transmitted by Fecal Microbiota Transplant. The New England journal of medicine. 2019;381(21):2043-2050.

86. Yelin I, Flett KB, Merakou C, et al. Genomic and epidemiological evidence of bacterial transmission from probiotic capsule to blood in ICU patients. Nature medicine. 2019;25(11):1728-1732.

87. Zmora N, Zeevi D, Korem T, Segal E, Elinav E. Taking it Personally: Personalized Utilization of the Human Microbiome in Health and Disease. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;19(1):12-20.

88. Johnson AJ, Vangay P, Al-Ghalith GA, et al. Daily Sampling Reveals Personalized Diet-Microbiome Associations in Humans. Cell Host Microbe. 2019;25(6):789-802.e785.

89. Djulbegovic B, Guyatt GH. Progress in evidence-based medicine: a quarter century on. Lancet (London, England). 2017;390(10092):415-423.

90. Bothwell LE, Podolsky SH. The Emergence of the Randomized, Controlled Trial. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(6):501-504.

91. Zeilstra D, Younes JA, Brummer RJ, Kleerebezem M. Perspective: Fundamental Limitations of the Randomized Controlled Trial Method in Nutritional Research: The Example of Probiotics. Adv Nutr. 2018;9(5):561-571.

92. Guarino A, Canani RB. Probiotics in Childhood Diseases: From Basic Science to Guidelines in 20 Years of Research and Development. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016;63 Suppl 1:S1-2.

93. Crow D. Microbiome Research in a Social World. Cell. 2018;172(6):1143-1145.

94. Cohen PA. Probiotic Safety-No Guarantees. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(12):1577-1578.

95. Dauby N. Risks of Saccharomyces boulardii-Containing Probiotics for the Prevention ofClostridium difficile Infectionin the Elderly. Gastroenterology. 2017;153(5):1450-1451.

96. Pararajasingam A, Uwagwu J. Lactobacillus: the not so friendly bacteria. BMJ case reports. 2017;2017:bcr2016218423.

97. Shanahan F, Hill C. Language, numeracy and logic in microbiome science. Nature reviews Gastroenterology & hepatology. 2019;16(7):387-388.

98. Mozaffarian D. Conflict of Interest and the Role of the Food Industry in Nutrition Research. JAMA. 2017;317(17):1755-1756.

99. Galea S, Saitz R. Funding, Institutional Conflicts of Interest, and Schools of Public Health: Realities and Solutions. JAMA. 2017;317(17):1735-1736.

100. Nissen SE. Conflicts of Interest and Professional Medical Associations: Progress and Remaining Challenges. JAMA. 2017;317(17):1737-1738.

101. Sox HC. Conflict of Interest in Practice Guidelines Panels. JAMA. 2017;317(17):1739-1740.

102. Greenhalgh S. Making China safe for Coke: how Coca-Cola shaped obesity science and policy in China. BMJ. 2019;364:k5050.

103. Barnard ND, Willett WC, Ding EL. The Misuse of Meta-analysis in Nutrition Research. JAMA. 2017;318(15):1435-1436.

104. Hughes HK, Landa MM, Sharfstein JM. Marketing Claims for Infant Formula: The Need for Evidence. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(2):105-106.

105. The L. Dietary supplement regulation: FDA's bitter pill. Lancet (London, England). 2019;393(10173):718-718.

106. Hanage WP. Microbiology: Microbiome science needs a healthy dose of scepticism. Nature. 2014;512(7514):247-248.

107. Fischbach MA. Microbiome: Focus on Causation and Mechanism. Cell. 2018;174(4):785-790.

108. Kleerebezem M, Binda S, Bron PA, et al. Understanding mode of action can drive the translational pipeline towards more reliable health benefits for probiotics. Current opinion in biotechnology. 2019;56:55-60.

109. Knight R, Vrbanac A, Taylor BC, et al. Best practices for analysing microbiomes. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2018;16(7):410-422.

110. Aagaard K, Hohmann E. Regulating microbiome manipulation. Nat Med. 2019;25(6):874-876.

111. Hoffmann D, Palumbo F, Ravel J, Roghmann MC, Rowthorn V, von Rosenvinge E. Improving regulation of microbiota transplants. Science. 2017;358(6369):1390-1391.

112. Verbeke F, Janssens Y, Wynendaele E, De Spiegeleer B. Faecal microbiota transplantation: a regulatory hurdle? BMC Gastroenterol. 2017;17(1):128.

113. Green JM, Barratt MJ, Kinch M, Gordon JI. Food and microbiota in the FDA regulatory framework. Science. 2017;357(6346):39-40.

114. Shamarina D, Stoyantcheva I, Mason CE, Bibby K, Elhaik E. Communicating the promise, risks, and ethics of large-scale, open space microbiome and metagenome research. Microbiome. 2017;5(1):132.

115. Dominguez-Bello MG, Peterson D, Noya-Alarcon O, et al. Ethics of exploring the microbiome of native peoples. Nat Microbiol. 2016;1(7):16097.

116. Rhodes R. Ethical issues in microbiome research and medicine. BMC Med. 2016;14(1):156.

117. O'Doherty KC, Virani A, Wilcox ES. The Human Microbiome and Public Health: Social and Ethical Considerations. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(3):414-420.

118. Stead WW. The Complex and Multifaceted Aspects of Conflicts of Interest. JAMA. 2017;317(17):1765-1767.

119. Untangle food industry influences on health. Nat Med. 2019;25(11):1629.

120. Thornton JP. Conflict of Interest and Legal Issues for Investigators and Authors. JAMA. 2017;317(17):1761-1762.

121. Zuger A. What Do Patients Think About Physicians' Conflicts of Interest?: Watching Transparency Evolve. JAMA. 2017;317(17):1747-1748.