编者按:

之前,我们特别报道了利用肠导向催眠法治疗肠易激综合症(IBS):肠道会说话?好好和它沟通或可治疗 IBS?诺奖大佬也在攻关!

今天,我们关注另一种治疗手段:抗抑郁药物。抗抑郁药物通常用于治疗炎症性肠病(IBD)的焦虑和抑郁症状。而最近研究表明,IBD 活动与个人情绪状态之间存在联系,这增加了抗抑郁药可能会改变 IBD 病程的可能性。

抗抑郁药物与 IBD 究竟存在怎样的互作机制?我们有可能用抗抑郁药物治疗 IBD 吗?

今天,我们特别编译发表在Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology 上关于如何利用抗抑郁药物治疗 IBD 的综述。希望该文为相关人士带来一些帮助与启发。

以下是全文编译:

摘要

科学界公认脑-肠失调是了解慢性胃肠疾病的关键,而且这一方向已经演变成为一门新的学科,心理胃肠病学。连同心理治疗一起,抗抑郁药物(中枢神经调节药物中的一类)可作为脑-肠失调疾病的治疗手段,以同时实现恢复心理健康和胃肠健康的效果。

抗抑郁药已被证实可用于焦虑症和抑郁症共病患者的治疗,还能解决疼痛以及睡眠障碍等问题。尽管抗抑郁药在脑-肠互作障碍疾病(disorders of gut–brain interaction,DGBI)中的疗效已被证实,但其用于 IBD 治疗的相关数据才刚刚出现。

本篇综述将讨论抗抑郁药在 DGBI 和 IBD 中的应用,重点讨论如何利用抗抑郁药物在 DGBI 中的经验知识以优化 IBD 治疗。

以下是正文:

作为一种常见疾病,胃肠道疾病严重困扰着人们的生活1~3,对个人和社会造成了巨大负担,并产生了严重的经济损失4,5。

人们对脑-肠交流的日益重视6、胃肠病患者中焦虑症和抑郁症的高患病率7,8,以及研究发现精神疾病对胃肠道功能紊乱具有一定影响(反之亦然)的结论9,10,这些因素促成了心理胃肠病学成为一个新的研究领域。

心理胃肠病学11是指利用胃肠病学和心理学的知识来治疗胃肠疾病,并在多学科护理模式下采取脑-肠疗法(包括心理疗法和抗抑郁药治疗)对胃肠不适和相关的精神疾病进行治疗。(相关的心理疗法信息见 Box 1)

除了心理疗法12,抗抑郁药物也是一种常见的脑-肠治疗手段。由于它们在治疗胃肠道疾病方面的作用超过了用于治疗精神疾病的意义,这些抗抑郁药物现在被定义为中枢神经调节药物13。

本篇综述讨论了抗抑郁药物在治疗 IBD 方面的应用。我们将阐述它们的作用机制及其在 DGBI 中发挥作用的方式,并探讨了其作为一种新兴的治疗方法可以如何优化以治疗 IBD 的某些特定症状,如慢性疼痛和肠功能障碍。

Box :心理疗法应用于胃肠病学

心理疗法,或谈话疗法,在此过程中,患者与医师定期见面讨论病人生活的各个方面,通过谈话提升患者的幸福感。虽然心理治疗通常都涉及到信任这一交流共同元素,但不同类型的心理治疗具有不同的理论、应用手段,以及能够改变患者行为、习惯和潜在驱动因素的假设机制。

认知行为疗法(CBT)、心理动力疗法、肠导向催眠疗法和其他心理疗法已被广泛应用于胃肠病学11。

一项荟萃分析汇总了 IBS 中的心理疗法随机对照实验。IBS 是一种 DGBI(之前被称为功能性胃肠疾病),该实验证实了认知行为治疗、催眠治疗、多重心理治疗和动态心理治疗在改善 IBS 症状方面的疗效91。

另一项荟萃分析显示,各种心理疗法(认知行为疗法、催眠疗法、精神动力疗法和放松疗法)的效果相当,但是认知行为疗法对患者日常生活的改善最大151。

在 DGBI 中,心理治疗常被用作一种辅助治疗,与抗抑郁药物相结合,治疗患有严重胃肠道症或共病患者13,152。

IBD 是一种常伴随 DGBI 的胃肠道疾病129,心理治疗疗效的证据不如 DGBI 的有力,有效性数据仅限于短期改善生活质量和抑郁指数,并没有改善疾病活动或治疗后的长期影响153。

关于胃肠疾病心理治疗的未来发展,特别是依赖于弹性、乐观和自我调节的积极心理学解决方案,已经在之前的文章全面讨论过12。

脑-肠失调

DGBI 是指中枢神经系统(CNS)处理加工和肠道功能间互作发生失调,之前也被称为功能性肠紊乱6。

肠道功能表达失调包括肠蠕动失调,内脏超敏反应和肠粘膜、免疫和肠道菌群完整性改变,这些都会导致肠道出现一系列病症。肠道功能的改变可由多种因素触发如感染、创伤或虐待史等,而压力、适应不良、焦虑和抑郁等可能导致改变难以恢复14。

焦虑和抑郁不仅在 DGBI 中十分常见7,在双向的脑-肠互动中也十分常见。在后期发展中发现,无 DGBI 共病的心理疾病患者会逐渐出现肠道病症,而无焦虑症或抑郁症共病的 DGBI 患者会逐渐出现心理疾病症状9。

据报道,疾病感染时的压力与患病后 IBS 的发展呈正相关15~17,因为它能启动中枢神经系统、微生物和粘膜免疫的级联反应,进而导致疾病的发作。

同样,压力也是 IBD 病程强有力的预测因子之一18。IBD 是一种复杂的、多因素的胃肠道疾病。在环境因素的影响下,免疫系统对肠道菌群活动的过度应答会引发该疾病。因此,和 IBS 一样,IBD 逐渐也被视为一种脑-肠轴失调所引发的疾病。

另外,焦虑症和抑郁症不仅与恶化的 IBD 表现有关19,它们似乎还与住院率20和手术发生率的增加有关21。2018 年的一项前瞻性研究首次提出了 IBD 疾病中存在的双向交流现象10,这一点和 DGBI 类似。

在这项观察性的研究中,研究人员发现,与基线时处于静态期的患者相比,处于疾病活跃状态的无焦虑症共病的 IBD 患者其后续焦虑症的发病率风险增加 6 倍10。另一方面,IBD 病症处于缓解期的焦虑症患者,后续 IBD 的复发、需要类固醇治疗或升级版 IBD 治疗的风险提高了 2 倍。

此外,慢性疼痛,内脏和中枢敏化均是 IBD 的常见症状(DGBI 也如此22)。在 IBD 中,即使患者处于疾病的缓解期,发生的炎症依然会导致敏化23,24。而 IBD 疾病中的慢性疼痛是脑-肠交流失调的结果25,心理因素可以通过脑-肠轴作用影响疼痛阈值23,26。有研究显示具有慢性疼痛和 IBD 疾病的患者抑郁和焦虑的患病率会升高27。

无论如何,脑-肠交流产生的影响远远不止 IBD 中的抑郁、焦虑、疼痛和疾病活动度,两者之间的相互作用可以在治疗过程中进一步体现。

不论成年人还是青少年,焦虑和/或抑郁症状的患者都难以坚持常规的治疗28,29。而在控制人口统计学、疾病类型和精神疾病史后,抑郁症状仍然是随访过程中判断是否按时服用抗 TNF 药物进行疾病治疗的一个重要预测指标30。

此外,尽管在 IBD 和其他炎症患者进行免疫抑制治疗(特别是英夫利昔单抗和维多珠单抗)后焦虑和抑郁症状有所缓解31~34 ,但是英夫利昔单抗治疗失败后也会导致抑郁35。

荟萃分析进一步提出细胞因子在焦虑和抑郁中的作用,细胞因子调节药物可以用于治疗那些患有慢性炎症的焦虑症和抑郁症患者36,37。

另一个荟萃分析显示,与安慰剂相比,非甾体抗炎药(NSAIDs)对抑郁症状有缓解作用38。与普通安慰剂对照,用英夫利昔单抗治疗双向抑郁,结果显示英夫利昔单抗减少了曾遭受身体虐待或性虐的受试者们的抑郁症状(蒙哥马利-艾森贝格抑郁量表测试总分降低超过 50%),但对其他病人无效39。一项概念验证性研究显示英夫利昔单抗能够改善高炎病人的抑郁和焦虑症状40。

图 1 对相关研究进行了总结。

图1. IBD 中的脑肠互作概述:抗炎药物可能具有抗抑郁和抗焦虑的疗效,反之,抗抑郁和抗焦虑治疗也可能在炎症治疗中占有一席之地。CD:克罗恩病;UC:溃疡性结肠炎。

总之,这些研究都表明抗炎症药物治疗可能具有抗抑郁和抗焦虑的疗效,因此,抗抑郁和抗焦虑治疗可能在炎症治疗中占有一席之地,这为抗抑郁药物作为 IBD 的辅助治疗手段提供了依据。

抗抑郁药物作用机制

抗抑郁药物,以及抗精神病药物和其他靶向中枢神经系统的药物目前被统称为中枢神经调节药物,而它们的作用不止于应对精神疾病13。

抗抑郁药物是最常见的药物治疗手段之一41,在过去一个月里, 12 岁以上的美国人中,近 13%在服用抗抑郁药物42。

FDA 规定抗抑郁药物的主要适应症包括抑郁症、焦虑和其他精神疾病(如创伤后压力心理障碍症和强迫症)。人们普遍认为抗抑郁药可以补偿缺失的神经递质,而神经递质缺失被认为是导致精神疾病的潜在原因43。

所谓的“单胺假说”将抑郁症和焦虑症定义为大脑回路中血清素(又称为 5-羟色胺)、去甲肾上腺素和多巴胺的缺乏,这些物质都是神经元释放的单胺类神经递质44,45。神经传递后,突触转运体促进血清素、去甲肾上腺素和多巴胺的再吸收,使它们重新进入神经元,以被再利用。

如果转运体被抑制,神经元外的单胺类神经递质水平将增加。

抗抑郁药能够通过阻断转运体、在突触间隙保留神经递质以及下调突触后受体或使其脱敏的方式促进这些单胺物质的突触活动13,46。

而血清素、去甲肾上腺素和多巴胺的增加被认为可以改善焦虑和抑郁的症状,但是,据服用抗抑郁药物患者的反馈,这一过程也会导致一系列的副作用,如焦虑、焦虑、失眠、性功能障碍、恶心和呕吐(见表 1)。

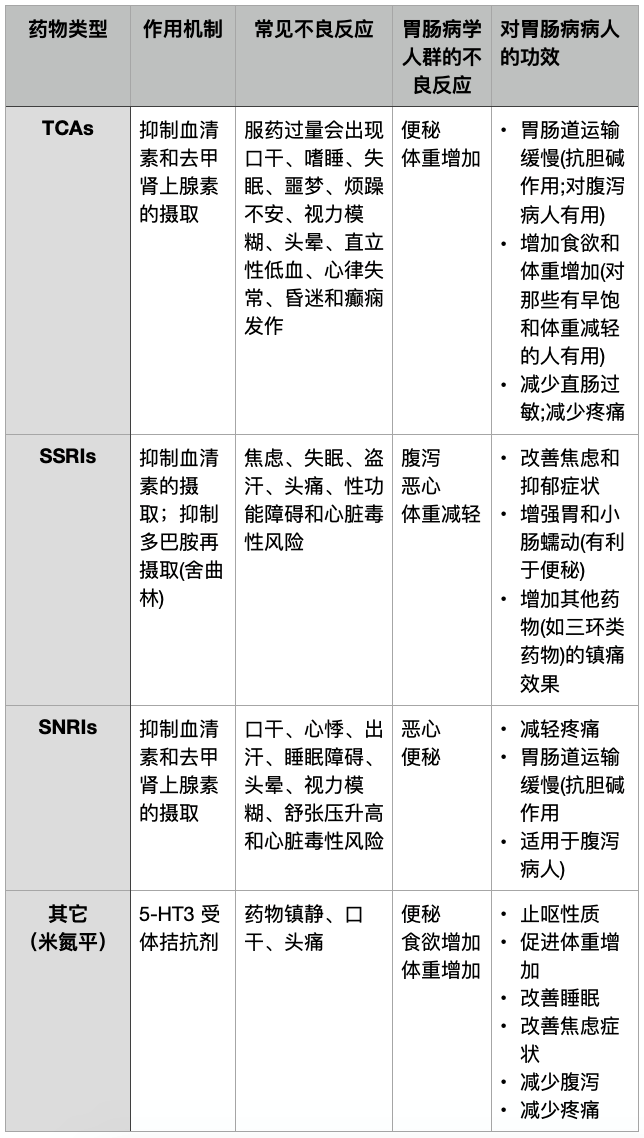

表 1. 抗抑郁药物在脑肠互作障碍中的作用机制、不良反应和功效;5-HT3 :5 -羟色胺;SSRIs:血清素和去甲肾上腺素再摄取抑制剂;SNRIs:选择性血清素再摄取抑制剂;TCA:三环抗抑郁药。

另一种抑郁症病原学理论强调了炎症机制在疾病进程中的作用,因为血浆中促炎细胞因子(如 TNF、IL-1 和 IL-6)的分泌水平被发现能够预测抑郁症的发病47。另外,研究还发现血清中 C 反应蛋白、干扰素-γ、以及肿瘤坏死因子 TNF 水平在广泛性焦虑障碍患者中升高48。

因此,抗抑郁药物被进一步认为是通过免疫调节通路降低促炎症因子如 TNF、IL-6、IL-1β 和 IL-10 的水平治疗精神疾病的49~53。

另外,犬尿氨酸通路的激活(炎症状态影响下,色氨酸能够转化为犬尿氨酸而非 5-羟色胺)已在动物实验中被证实与类抑郁状态相关,并且该激活过程被认为是抑郁症状的诱因。

不仅仅是犬尿氨酸通路的激活,神经毒性代谢物与神经保护代谢物之间的稳态破坏也可能是导致抑郁症的原因54。

在 2017 年的一项研究中,起初抑郁症患者犬尿氨酸水平低于对照组,而在 8 周的抗抑郁药物(帕罗西汀、度洛西汀、米氮平或舍曲林)治疗后,犬尿氨酸水平上升了,这一实验结果暗示了抗抑郁药物对抗抑郁症的新的作用机制55。

虽然服用抗抑郁药物并没有使病人掌握战胜回避或其它类型功能障碍的方法以缓解病情和防止复发,但是抗抑郁药物通常被认为是应对常见心理疾病的一种替代心理疗法的治疗手段,两者具有类似的治疗效果56,57。

尽管抗抑郁药和心理疗法都与安慰剂效应有关58,59,但是抗抑郁药对抑郁症(尤其是轻度至中度抑郁症)的疗效仍存在争议60,61。尽管存在争议,但是一项荟萃分析表明,抗抑郁药物与心理治疗相结合比两者单独使用在焦虑症和抑郁症的治疗上更加有效62。

这是因为这两种方法是独立运作且作用互补的,它们作用于大脑的不同区域。

心理疗法作用于前额叶皮层内的区域(负责认知)、基底神经节以及大脑边缘区域63,而抗抑郁药物则主要作用于大脑边缘区域(负责情绪调控)以及额叶皮质64,65。

因此,用抗抑郁药改善情绪可能会提高心理疗法改善认知的能力,反之亦然,使用心理疗法可改善对抗抑郁药物的依赖性66。

抗抑郁药物在胃肠病中的价值和应用已经被广泛研究和讨论13,14,46,67,68。在这些研究中,它们通常在监管机构批准之外使用,被认为是“药品核准标示外使用”。

事实上,目前没有抗抑郁药物被批准作为肠道疾病治疗药物,但是它们却是目前用于治疗 DGBI 最常见的药物之一:有八分之一的 IBS 患者在使用抗抑郁药物进行胃肠病治疗69,在北美,30%~55%的相关疾病患者在服用此类药物70,71。

有意思的是,有两种血清素和两种去甲肾上腺素再摄取抑制剂(具体为度洛西汀、米那普仑)已经被批准作为另一种慢性疼痛——纤维组织肌痛的首选治疗用药72,而度洛西汀还可用于周围神经病变和慢性疼痛73,74。

抗抑郁药物被认为是通过调控神经递质(如血清素,去甲肾上腺素和促肾上腺皮质激素释放因子)来应对胃肠病症的,这些神经递质对于肠道蠕动和感应意义非凡75。它们还通过阻断血清素、去甲肾上腺素和其他几种神经递质受体产生镇痛效果76。

另外,它们可以减少肠道的传导信号77,并可能通过影响前扣带皮层功能来下调传入的内脏信号78。

然而,另一种理论提出了抗抑郁药物对神经发生的作用77,79。心理创伤会导致神经元的丢失80,而在抗抑郁药物或心理疗法等治疗的影响下,神经元会再生。与胃肠病学相关的是,DGBI 患者已被证实大脑结构发生改变81。

抗抑郁药被认为或可恢复失去的神经元,研究证实,在抗抑郁药物治疗过程中,脑源性神经营养因子水平会随之升高,进而可促进神经发生,而这种脑源性神经营养因子水平升高似乎与抑郁症的恢复程度相关79,82。

另外,延长这些药物的服用疗程可以促进神经发生并降低抑郁症复发的风险82~84。

DGBI治疗中的抗抑郁药物

在 DGBI 中,抗抑郁药物通常被用来解决与原疾病共发的心理问题(如焦虑、抑郁和疼痛恶化),以及腹痛、尿急和排便频率高、便秘、恶心和睡眠质量不佳等问题13,46,85。抗抑郁药被建议作为中重度患者、生活质量下降患者以及使用其它治疗办法(如饮食或服用东莨菪碱和奥替溴铵等解痉药)但未得到理想效果的患者们的治疗方法13,46,85。

有三类常见的抗抑郁药物被用于 DGBI 中:三环抗抑郁药物(TCAs)、选择性 5-羟色胺再摄取抑制剂 (SSRIs)以及血清素和去甲肾上腺素再摄取抑制剂(SNRIs)。另外,非典型抗抑郁药(如米氮平)也被应用于 DGBI 治疗中。

三环抗抑郁药物(TCAs)

TCAs 对疼痛敏感症状尤其有效,尽管这一发现来自于急性、持续性和神经性疼痛的动物模型86。TCAs 的镇痛作用与抗抑郁作用无关,因为它们对包括 DGBI 在内的非精神病理性的慢性疼痛综合征疗效也十分显著,并且是低“非精神性”剂量的85。它们还可能缓解结肠超敏反应87。

就安全性而言,典型的不良反应包括镇静、抗胆碱能作用(尽管 TCAs 减慢小肠和结肠蠕动而导致便秘的效果或可用于处理以腹泻为主要症状的胃肠道疾病88)、失眠、噩梦和躁动89。

较地昔帕明和去甲替林,使用阿米替林和丙咪嗪可能具有更明显的副作用, 因为阿米替林和丙咪嗪是叔胺类 TCAs,具有很强的抗组胺和抗胆碱能作用90。

对 IBS 和功能性消化不良的荟萃分析已经证明了 TCAs 对包括疼痛在内的肠道症状的疗效:抗抑郁药物治疗组中约有 57%的患者得到了症状改善,而安慰剂治疗组中只有 36%的患者得到了症状改善91。

选择性血清素再摄取抑制剂 (SSRIs)

SSRIs 在应对肠道性疼痛的表现不及 TCAs86,这可能是因为它们对去甲肾上腺素没有影响。但是,仍然存在一些初步研究表明该类药物在应对非心源性胸痛上的作用95。其实,它们在 DGBI 中的主要功效是缓解抑郁与焦虑症状。它们还可能增强使用 TCAs 的效果,特别是在治疗焦虑方面13。

该药物的副作用与 TCAs 相比较少,包括躁动、失眠、性功能障碍、恶心或腹泻。SSRIs 可能更适用于便秘型 DGBI 患者88。

有随机对照实验的荟萃分析显示,服用 SSRIs 的患者中有 55%的 IBS 症状得到改善,而服用安慰剂的患者中只有 33%的 IBS 症状得到改善91,尽管各个研究结果之间存在很大差异。然而,另一项荟萃分析却指出 SSRIs 在功能性消化不良上作用甚微92。

血清素和去甲肾上腺素再摄取抑制剂(SNRIs)

SNRIs(如度洛西汀和文拉法辛),可以缓解疼痛相关症状,并且比 TCAs 副作用少73。度洛西汀可治疗包括糖尿病性神经病疼痛、纤维肌痛和慢性肌肉骨骼痛96。副作用包括恶心、便秘和口干,但是便秘和口干的发生较 TCAs 更少73,89。

非盲非对照实验显示服用 SNRIs 可缓解疼痛、治疗 IBS、改善抑郁症焦虑症、提高工作生活质量和家庭氛围,除了非盲非对照治疗外,胃肠疾病方面的研究结果很少97~99。

其它抗抑郁药物

米氮平是一种具有很强抗抑郁功效的四环类抗抑郁药,具有增加体重、改善睡眠和治疗睡眠困难的功效,尤其是针对功能性消化不良相关的体重减轻、餐后抑郁综合症、慢性恶心和呕吐等问题67,100,101。

噻奈普汀是一种非典型的抗抑郁药物。一项非盲研究显示该药与阿米替林在全球性防治腹泻型 IBS 方面具有类似的疗效,并且噻奈普汀组口干舌燥和便秘等副作用较少102。

优劣分析

抗抑郁药对于应对 DGBI 可能是有效的,原因如表 1 所示68:

(1)可以帮助治疗常见的精神疾病合并症;

(2)可以帮助减轻疼痛;

(3)改善睡眠质量——疼痛和睡眠问题是 DGBI 中常见的症状,该症状会加剧病症和降低生活质量103;

(4)可能通过改变内脏传入信号来降低内脏敏感性(尽管仍存在争议)104 ,105。

(5)可以通过胆碱能、去甲肾上腺素能和 5 -羟色胺调节肠道蠕动和分泌物水平88,106;

(6)对内脏平滑肌具有舒缓作用14。

另一方面,抗抑郁药物存在有目共睹的副作用(表 1)。值得注意的是,很多抗抑郁药物会造成胃肠道的不良反应,通常这些反应是暂时的,但也可能会导致已经有严重胃肠道症状的患者放弃相关治疗。

研究还发现,早期的不良反应更多地与服药引起的焦虑有关,而非实际治疗产生的不良反应107。因此,确保治疗的进行,定期随访患者监测症状变化是很有必要的77。

另一个对这些使用抗抑郁药物的病人密切观察的原因是这些药物是在药品核准标示外使用于胃肠疾病,其中部分抗抑郁药物的研究数量有限,所以面临的风险未知。

争议仍旧存在,比如说,SSRI 类药物的使用是否与消化道出血有关108。虽然似乎关联性不强,但 SSRIs 与非甾体类抗炎药或阿司匹林同时使用会大大增加风险108。另外,在使用 TCAs 时,可能会降低癫痫发作阈值109, 这可能与胃肠疾病患者有关。

重要的是,通过联合使用不同的抗抑郁药物,或抗抑郁药物与阿片类药物(如曲马多)协同使用,不良反应的风险会增加,危及生命的血清素综合征(血清素的过度积累)的患病风险也会增加110,111。因此,在联合治疗中药物的剂量通常会减少,造成净效应不会大幅增加。

此外,一些抗抑郁药物服用剂量需要逐渐减少以避免戒断综合症46,112,113。

抗抑郁药物在IBD中的作用

在西方国家,10%~30%的 IBD 患者服用抗抑郁药物114~116;但是,与 DGBI 相比,它们应对 IBD 的功效还有待考证。到目前为止,系统性综述117~120以及叙述性综述121都提及了抗抑郁药物对于 IBD 病人的疗效,但是同时也指出了证据的牵强性,因此,抗抑郁药物对于 IBD 的治疗作用还需进一步的研究。

迄今为止,只有 3 项抗抑郁药物进行了 IBD 的安慰剂对照研究122~124,其中一项是非随机的122:

(1)噻奈普汀:噻奈普汀是一种非典型抗抑郁药物,与安慰剂对照组相比,在为期 12 个月的研究中,噻奈普汀减轻了焦虑和抑郁症状并降低了 60 名 IBD 患者的疾病活动指数122。

(2)度洛西汀:与安慰剂组相比,度洛西汀降低了 44 名患者的焦虑和抑郁指数,提高了生活质量并降低了临床疾病活动指数123。

(3)氟西汀: 尽管氟西汀对机体免疫功能存在一些影响(可升高效应记忆 T 辅助细胞比例,降低效应记忆 T 细胞毒性细胞比例),但是,与安慰剂组相比,在 6 个月的观察研究发现,氟西汀对 26 名患者的焦虑和抑郁指数、生活质量水平以及临床疾病活动指数并无改善124。

与之相关的是,一些观察性研究也对抗抑郁药物在 IBD 中的应用进行了实验。

在一项超过 4 万名参与者的大型观察性研究中,使用抗抑郁药物的患者与未使用药物的患者相比,IBD 活动指数较低(使用包括卫生保健和药物利用在内的疾病活动检测指标)125。

在另一项针对超过 40 万人的大型流行病学研究中,使用抗抑郁药物似乎可以降低抑郁症患者新发 IBD 的患病风险126。

在一项前瞻性研究中,有 331 名 IBD 患者参与,结果发现,接受抗抑郁药物治疗的患者药物升级的趋势较低,特别是对于那些在实验开始时具有不正常的焦虑或抑郁指数的患者127。

在一项回顾性病例记述评估中,与对照组相比,58 名 IBD 患者,服用不同类别抗抑郁药物的患者在一年内逐渐好转并具有更低的疾病复发率和类皮质激素疗程需求(研究匹配了年龄、性别、疾病类型、基线时用药和一年内的复发率)128。

抗抑郁药在IBD中的潜在作用

应对心理合并症

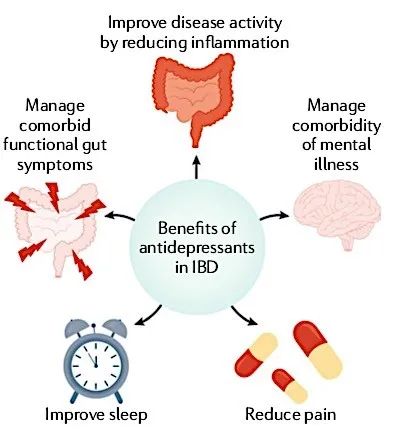

肠脑疗法用于治疗 IBD 具有很大的应用潜力,抗抑郁药物有 5 种可能的物种功效(图 2)。

首先,约有 28%的 IBD 进入病情缓解期患者报告有焦虑症状,66%的 IBD 爆发期患者报告有焦虑症状;而有 20%缓解期 IBD 患者和 35% IBD 爆发期患者报告有抑郁症状8。正如前面提到的两个小型试验一样,抗抑郁药可能有助于治疗这些心理合并症122,123。

图 2. 抗抑郁药在 IBD 中的未来应用:应用脑-肠疗法在治疗 IBD 方面有很大的应用潜力,抗抑郁药物对于 IBD 疾病治疗的五项潜在功效。

应对肠道合并症

抗抑郁药物可以帮助控制 IBD 肠道功能性合并症。高达 40%的 IBD 患者的症状与 IBS 相一致,因此也被称为“IBD 中的 IBS”129。即使是处于恢复期的患者,也有 25%的病人符合 IBS 诊断标准130。

一项有 158 名 IBD 患者参与的观察性研究提供了有力证据:尽管炎症得到控制,但 IBD 患者仍会有遗留的胃肠症状,而 TCAs 能够改善这些症状131。另外,慢性腹泻在 IBD 缓解期中非常常见,而 TCAs 能够有效减缓直肠蠕动88,因此抗抑郁药物或可解决这些肠道合并症。

缓解慢性疼痛

抗抑郁药物可能会缓解与 IBD 相关的慢性疼痛,从而减少对阿片类药物依赖。近 40%的 IBD 患者具有持续疼痛的症状132,15%服用阿片类药物115,高达 70%的住院患者使用麻醉药物133。约有 70%的 IBD 患者报告有疼痛感,这是由于 IBD 疾病深入神经层、阻塞、纤维化或感染所致134。急性疼痛时,肠壁感觉传入神经通过脊髓后角向中枢神经系统发送信号135。

然而,由于炎症在 IBD 中反复发生,一些患者会发展为内脏超敏反应136并在缓解期也发生慢性疼痛。这种情况在“IBD 中的 IBS”中尤为明显,尽管在该情况下肠粘膜炎症是有限或者不存在的,但是疼痛与炎症导致的外周敏化有关23 ,24。

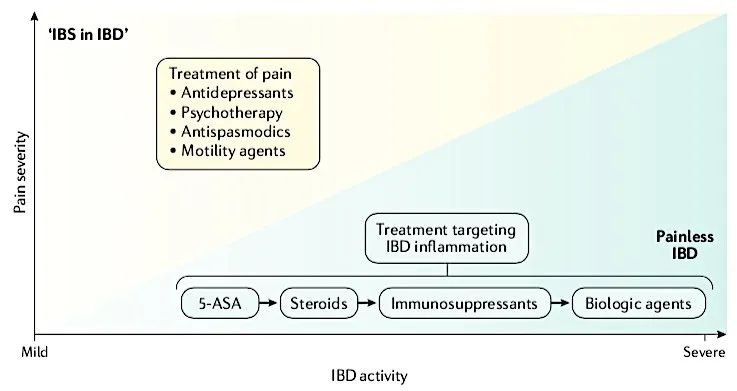

重要的是,胃肠道中的疾病活动并不是准确的 IBD 疼痛预测因子。一些患有严重 IBD 的病人几乎没有疼痛症状,而有些轻微 IBD 患者或者痊愈的 IBD 患者即使在服用药物也存在剧烈疼痛的现象137。

因此,疼痛可能是由生物、心理、社会因素引起的,而不是由炎症的严重程度引起的23,138。

正如前面讨论的那样,这方面的核心问题是内脏和中枢敏化22,因为即使患者处于缓解期,IBD 中的炎症变化仍然可以导致敏化23,24。虽然在 IBD 的研究中还未涉及抗抑郁药物对疼痛的影响,但它们可能产生对 DGBI 类似的镇痛效果94,特别是考虑到一些抗抑郁药物正在被广泛应用于疼痛综合症72。

图 3 说明了疼痛和 IBD 活动之间的关系,并为使用抗抑郁药治疗 IBD 疼痛提供了指导意义。在这个模型中,抗抑郁药可用于治疗疼痛,无论疼痛是直接由当前的炎症过程引起,还是由慢性疼痛中常见的致敏作用引起,均能够在疼痛发作和缓解期间提高疼痛阈值。

另外,可以通过逐步增加疾病修饰药物来治疗更严重的炎症活动。

图 3. IBD 活动并非总是与疼痛程度直接相关:有些严重 IBD 患者是无疼痛症状的,而剧烈疼痛症状可能会导致 “IBD 中 IBS”的发生,而非 IBD 活动。抗抑郁药物可用来治疗疼痛(由活动性疾病导致、炎症性肠病中的肠易激综合征或心理因素造成)。需要注意的是图片并不是为了强调最新的疾病应对方法,而是为了说明疾病活动与疼痛严重程度之间的区别。5-ASA 是 5-氨基水杨酸。

改善睡眠质量

抗抑郁药物或可通过改善睡眠质量间接对 IBD 产生有益效果。

IBD 患者往往伴随日益加重的睡眠问题139,而睡眠质量不好与活动性疾病的发作有关140。尽管没有证据表明抗抑郁药物改善 IBD 患者的睡眠质量,但在治疗普通人群失眠问题时,抗抑郁药物在调控睡眠困难方面的作用已得到充分证实141。

然而,需要强调的是,迄今为止关于各种治疗失眠方法的疗效的证据并不充分。科克伦的一项研究表明,抗抑郁药、针灸、音乐和体育锻炼对失眠患者都有一定的好处142。认知和行为疗法对睡眠问题也很有效143,144。然而,关于这些治疗的证据质量都在中等及以下,因此亟需进一步的研究。

减少炎症

其实最振奋人心的是抗抑郁药物对炎症的潜在作用。

在 IBD 动物模型中,与安慰剂对照组相比,地昔帕明减少了微观损伤,降低了结肠髓过氧化物酶活性145。另外,在动物模型中,氟西汀和地昔帕明都可大幅度降低 IL-1β 和 TNF 的血清浓度(P <0.001)146。

唯一的一项探究炎症的 IBD 人体实验显示了抗抑郁药物在免疫功能中有限的作用124。在这个为期 6 个月的小型实验中(26 名参与者),氟西汀显著增加了效应记忆 T 辅助细胞比例,降低了效应记忆 T 细胞毒性细胞比例,而安慰剂只降低了 IL-10 水平。

另一项为期 12 个月的随访实验中发现,与安慰剂相比,噻奈普汀可显著改善疾病活动度指数(P < 0.01)122。这项实验还发现噻奈普汀可显著改善 C 反应蛋白和血红蛋白水平。

另外,一项研究发现,接受抗抑郁药物治疗后的 3 个月内服用度洛西汀,可显著降低患者 IBD 活动指数123。

虽然还没有炎症或抗抑郁治疗 IBD 背景下的犬尿氨酸通路的研究,但与慢性炎症相关的抑郁症被认为与其它类型的抑郁症存在病理学意义上的不同147,犬尿氨酸通路的改变只发生在这些慢性炎症抑郁症患者中148。

因此,靶向犬尿氨酸通路中的相关酶可能为同时治疗 IBD 和抑郁症(以及其他疾病如癌症)提供了新思路149,并且这种方法或可通过使用抗抑郁剂来实现55。

最后,重要的是要考虑这些药物在病人疾病爆发时、手术诱导的短肠综合征(“造口术”)或已知的肠道吸收不良时的吸收情况。在这些情况下,可能需要短效药物如米氮平或改用液体形式的抗抑郁剂150。

结论

抗抑郁药物常被用来治疗 DGBI。具体来说,它们能够同时治疗抑郁与焦虑症,减轻疼痛和改善睡眠质量。然而,它们的使用存在潜在风险,尤其在使用一种以上的抗抑郁药时,会产生特有的胃肠道副作用。

尽管抗抑郁药物在 DGBI 中的疗效已经得到证实,但是关于研究抗抑郁药物在 IBD 中作用的证据直到现在才出现。初步研究表明,抗抑郁药在处理精神性合并症、疼痛和睡眠问题方面有与 DGBI 类似的潜在功效。此外,抗抑郁药可以帮助解决共病症状、IBD 缓解期间的慢性腹泻以及减少炎症,进而改善疾病活动。

由于抗抑郁药物在 IBD 中的潜在用途多种多样,因此大型临床实验是十分必要的。目前,还不清楚哪一类或哪一种药物对 IBD 疗效最佳117。

迄今为止还没有应用抗抑郁药物治疗 IBD 的不良事件报道,所以抗抑郁药物治疗 IBD 似乎是安全的,但是招募人员进行随机对照实验仍然是一个巨大的挑战124,因此,亟需有大量患者参与的多种新项目。

众所周知,尤其是在治疗的早期,抗抑郁药会产生副作用,因此与治疗医生的定期沟通至关重要77。由于羞耻感,精神疾病患者会不愿意参加相关实验研究,所以,向患者解释脑-肠轴作用机制对于抗抑郁药物正常化使用也是十分必要的。

参考文献

(滑动下方文字查看)

1.National Commission on DigestiveDiseases. Opportunities and Challenges in Digestive Diseases Research:Recommendations of the National Commission on Digestive Diseases. (NationalInstitutes of Health, 2009).

2.Guadagnoli, L., Taft, T. H. &Keefer, L. Stigma perceptions in patients with eosinophilic gastrointestinaldisorders. Dis. Esophagus 30,1–8 (2017).

3.Taft, T. H., Riehl, M. E., Dowjotas,K. L. & Keefer, L. Moving beyond perceptions: internalized stigma in theirritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 26, 1026–1035 (2014).

4.Canavan, C., West, J. & Card, T.Review article:the economic impact of the irritablebowel syndrome. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 40, 1023–1034 (2014).

5.Everhart, J. E. & Ruhl, C. E.Burden of digestive diseases in the United States part I: overall and uppergastrointestinal diseases. Gastroenterology 136, 376–386 (2009).

6.Drossman, D. A. Functionalgastrointestinal disorders: history, pathophysiology, clinical features andRome IV. Gastroenterology 148,1262–1279 (2016).

7.Lee, C. et al. The increased levelof depression and anxiety in irritable bowel syndrome patients compared withhealthy controls: systematic review and meta- analysis. J.Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 23,349–362 (2017).

8.Mikocka-Walus, A., Knowles, S. R.,Keefer, L. & Graff, L. Controversies revisited: a systematic review of thecomorbidity of depression and anxiety with inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm.Bowel Dis. 22, 752–762(2016).

9.Koloski, N. A. et al. The brain–gutpathway in functional gastrointestinal disorders is bidirectional: a 12-yearprospective population-based study. Gut 61, 1284–1290 (2012).

10.Gracie, D. J., Guthrie, E. A.,Hamlin, P. J. & Ford, A. C. Bi-directionality of brain-gut interactions inpatients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 154, 1635–1646.e3 (2018).

11.Knowles, S., Keefer, L. &Mikocka-Walus, A. Psychogastroenterology for Adults: A Handbook for MentalHealth Professionals (Routledge, 2019).

12.Keefer, L. Behavioural medicine andgastrointestinal disorders: the promise of positive psychology.Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 15, 378–386 (2018).

13.Drossman, D. A. et al.Neuromodulators for functional gastrointestinal disorders (disorders ofgut-brain interaction): a Rome foundation working team report. Gastroenterology154, 1140–1171.e1 (2018).

14.Grover, M. & Drossman, D. A.Centrally acting therapies for irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterol.Clin. North. Am. 40, 183–206(2011).

15.Drossman, D. A. Mind over matter inthe postinfective irritable bowel. Gut 44, 306–307 (1999).

16.Barbara, G. et al. Rome foundationworking team report on post-infection irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology156, 46–58.e7 (2019).

17.Klem, F. et al. Prevalence, riskfactors, and outcomes of irritable bowel syndrome after infectious enteritis: asystematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 152, 1042–1054.e1 (2017).

18.Bernstein, C. N. et al. Aprospective population- based study of triggers of symptomatic flares in IBD. Am.J. Gastroenterol. 105,1994–2002 (2010).

19.Kochar, B. et al. Depression isassociated with more aggressive inflammatory bowel disease. Am. J.Gastroenterol. 113, 80–85(2018).

20.Barnes, E. L. et al. Modifiablerisk factors for hospital readmission among patients with inflammatory boweldisease in a nationwide database. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 23, 875–881 (2017).

21.Ananthakrishnan, A. N. et al.Psychiatric co-morbidity is associated with increased risk of surgery inCrohn’s disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 37, 445–454 (2013).

22.Grover, M., Herfarth, H. &Drossman, D. A.The functional-organic dichotomy:postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory boweldisease-irritable bowel syndrome. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 7, 48–53 (2009).

23.Drossman, D. A. & Ringel, Y. inKirsner’s Inflammatory Bowel Disease (eds. Sartor, R. B. & Sandborn,W.) 340–356 (Harcourt Publishers Limited, 2004).

24.Srinath, A. I., Walter, C., Newara,M. C. & Szigethy, E. M. Pain management in patients with inflammatory boweldisease: insights for the clinician. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 5, 339–357 (2012).

25.Mayer, E. A. & Tillisch, K. Thebrain-gut axis in abdominal pain syndromes. Annu. Rev. Med. 62, 381–396 (2011).

26.Regueiro, M., Greer, J. B. &Szigethy, E. Etiology and treatment of pain and psychosocial issues in patientswith inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology 152, 430–439.e4 (2017).

27.Jonefjall, B., Ohman, L., Simren,M. & Strid, H. IBS-like symptoms in patients with ulcerative colitis indeep remission are associated with increased levels of serum cytokines and poorpsychological well-being. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 22, 2630–2640 (2016).

28.Spekhorst, L. M., Hummel, T. Z.,Benninga, M. A., van Rheenen, P. F. & Kindermann, A. Adherence to oralmaintenance treatment in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 62, 264–270 (2016).

29.Mountifield, R., Andrews, J. M.,Mikocka-Walus, A. & Bampton, P. Covert dose reduction is a distinct type ofmedication non-adherence observed across all care settings in inflammatorybowel disease. J. Crohns Colitis 8,1723–1729 (2014).

30.Calloway, A. et al. Depressive symptomspredict anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy noncompliance in patients withinflammatory bowel disease. Dig. Dis. Sci. 62, 3563–3567 (2017).

31.Horst, S. et al. Treatment withimmunosuppressive therapy may improve depressive symptoms in patients with inflammatorybowel disease. Dig. Dis. Sci. 60,465–470 (2015).

32.Zhang, M. et al. Improvement ofpsychological status after infliximab treatment in patients with newlydiagnosed Crohn’s disease. Patient Prefer. Adherence 12, 879–885 (2018).

33.Stevens, B. W. et al. Vedolizumabtherapy is associated with an improvement in sleep quality and moodin inflammatory bowel diseases. Dig.Dis. Sci. 62, 197–206(2017).

34.Ertenli, I. et al. Infliximab, aTNF-alpha antagonist treatment in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: theimpact on depression, anxiety and quality of life level. Rheumatol. Int. 32, 323–330 (2012).

35.Persoons, P. et al. The impact ofmajor depressive disorder on the short- and long-term outcome of Crohn’sdisease treatment with infliximab. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 22, 101–110 (2005).

36.Kappelmann, N., Lewis, G., Dantzer,R., Jones, P. B. & Khandaker, G. M. Antidepressant activity of anti-cytokine treatment: a systematic review and meta- analysis of clinical trialsof chronic inflammatory conditions. Mol. Psychiatry 23, 335–343 (2018).

37.Abbott, R. et al. Tumour necrosisfactor-alpha inhibitor therapy in chronic physical illness: a systematicreview and meta-analysis of the effecton depression and anxiety. J. Psychosom. Res. 79, 175–184 (2015).

38.Kohler, O. et al. Effect ofanti-inflammatory treatment on depression, depressive symptoms, and adverseeffects: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. JAMAPsychiatry 71, 1381–1391(2014).

39.McIntyre, R. S. et al. Efficacy ofadjunctive infliximabvs placebo in the treatment of adultswith bipolar I/II depression: a randomized clinical trial.JAMAPsychiatry.https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.0779(2019).

40.Raison, C. L. et al. A randomizedcontrolled trialof the tumor necrosis factor antagonistinfliximab for treatment-resistant depression: the role of baselineinflammatory biomarkers. JAMA Psychiatry 70, 31–41 (2013).

41.OECD. Pharmaceutical market. OECDHealth Statistics (database). https://stats.oecd.org/Index. aspx?ThemeTreeId=9 (OECD, 2016).

42.Pratt, L. A., Brody, D. J. &Gu, Q. Antidepressant use among persons aged 12 and over: United States,2011–2014. NCHS Data Brief 283,1–8 (2017).

43.Ritter, J. M., Flower, R.,Henderson, G. & Rang, H. P. in Rang & Dale’s Pharmacology 603–622(Churchill Livingstone, 2015).

44.Schildkraut, J. J. Thecatecholamine hypothesis of affective disorders: a review of supportingevidence. Am. J. Psychiatry 122,509–522 (1965).

45.Hirschfeld, R. M. History andevolution of the monoamine hypothesis of depression. J. Clin. Psychiatry 61, 4–6 (2000).

46.Sobin, W. H., Heinrich, T. W. &Drossman, D. A. Central neuromodulators for treating functional GI disorders: aprimer. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 112,693–702 (2017).

47.Raedler, T. J. Inflammatorymechanisms in major depressive disorder. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 24, 519–525 (2011).

48.Costello, H., Gould, R. L., Abrol,E. & Howard, R. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the associationbetween peripheral inflammatory cytokines and generalised anxiety disorder. BMJOpen. 9, e027925 (2019).

49.Maes, M. The immunoregulatoryeffects of antidepressants. Hum. Psychopharmacol. 16, 95–103 (2001).

50.O’Brien, S. M., Scott, L. V. &Dinan, T. G. Antidepressant therapy and C-reactive protein levels. Br. J.Psychiatry 188, 449–452(2006).

51.Szuster-Ciesielska, A.,Tustanowska-Stachura, A., Slotwinska, M., Marmurowska-Michalowska, H.& Kandefer-Szerszen, M. In vitroimmunoregulatory effects of antidepressants in healthy volunteers. Pol. J.Pharmacol. 55, 353–362(2003).

52.Liu, J. J. et al. Peripheralcytokine levels and response to antidepressant treatment in depression: asystematic review and meta-analysis. Mol. Psychiatry 25, 339–350 (2020).

53.Wang, L. et al. Effects of SSRIs onperipheral inflammatory markers in patients with major depressive disorder: asystematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav. Immun. 79, 24–38 (2019).

54.Savitz, J. Role of kynureninemetabolism pathway activation in major depressive disorders. Curr. Top.Behav. Neurosci. 31, 249–267(2017).

55.Umehara, H. et al. Altered KYN/TRP,Gln/Glu, and Met/methionine sulfoxide ratios in the blood plasma ofmedication-free patients with major depressive disorder. Sci. Rep. 7, 4855 (2017).

56.Kirsch, I. et al. Initial severityand antidepressant benefits: a meta-analysis of data submitted to the food anddrug administration. PLoS Med. 5,e45 (2008).

57.Cuijpers, P., van Straten, A.,Bohlmeijer, E., Hollon, S. D. & Andersson, G. The effects of psychotherapyfor adult depression are overestimated: a meta-analysis of study quality andeffect size. Psychol. Med. 40,211–223 (2010).

58.Locher, C. et al. Efficacy andsafety of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin-norepinephrinereuptake inhibitors, and placebo for common psychiatric disorders amongchildren and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMAPsychiatry 74, 1011–1020(2017).

59.Enck, P. & Zipfel, S. Placeboeffects in psychotherapy: a framework. Front. Psychiatry 10, 456 (2019).

60.Munkholm, K., Paludan-Muller, A. S.& Boesen, K. Considering the methodological limitations in the evidencebase of antidepressants for depression:a reanalysis of a network meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 9, e024886 (2019).

61.Cipriani, A. et al. Comparativeefficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatmentof adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and networkmeta-analysis. Lancet 391,1357–1366 (2018).

62.Cuijpers, P. et al. Addingpsychotherapy to antidepressant medication in depression and anxiety disorders:a meta-analysis. World Psychiatry 13, 56–67 (2014).

63.Fournier, J. C. & Price, R. B.Psychotherapy and neuroimaging. Focus 12, 290–298 (2014).

64.Brody, A. L. et al. Brain metabolicchanges in major depressive disorder from pre- to post-treatment withparoxetine. Psychiatry Res. 91,127–139 (1999).

65.Seminowicz, D. A. et al.Limbic-frontal circuitry in major depression: a path modeling metanalysis. Neuroimage22, 409–418 (2004).

66.Pampallona, S., Bollini, P.,Tibaldi, G., Kupelnick, B. & Munizza, C. Combined pharmacotherapy andpsychological treatment for depression: a systematic review. Arch. Gen.Psychiatry 61, 714–719(2004).

67.Tornblom, H. & Drossman, D. A.Centrally targeted pharmacotherapy for chronic abdominal pain. Neurogastroenterol.Motil. 27, 455–467 (2015).

68.Levy, R. L. et al. in Rome IVFunctional Gastrointestinal Disorders — Disorders of Gut-Brain InteractionVol. 1 (eds. Drossman, D. A. et al.)443–560(Rome Foundation, 2016).

69.Whitehead, W. E. et al. The usualmedical care for irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 20, 1305–1315 (2004).

70.Drossman, D. A. et al.International survey of patients with IBS: symptom features and their severity,health status, treatments, and risk taking to achieve clinical benefit. J.Clin. Gastroenterol. 43,541–550 (2009).

71.Ladabaum, U. et al. Diagnosis,comorbidities, and management of irritable bowel syndrome in patients in alarge health maintenance organization.Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 10, 37–45 (2012).

72.Hauser, W., Wolfe, F., Tolle, T.,Uceyler, N. & Sommer, C. The role of antidepressants in the managementof fibromyalgia syndrome: a systematicreview and meta-analysis. CNS Drugs 26, 297–307 (2012).

73.Lunn, M. P., Hughes, R. A. &Wiffen, P. J. Duloxetine for treating painful neuropathy, chronic pain orfibromyalgia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, CD007115 (2014).

74.Kim, P. Y. & Johnson, C. E.Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: a review of recent findings. Curr.Opin. Anaesthesiol. 30,570–576 (2017).

75.Gershon, M. D. & Tack, J. Theserotonin signaling system: from basic understanding to drug development forfunctional GI disorders. Gastroenterology 132, 397–414 (2007).

76.Tracey, I. & Mantyh, P. W. Thecerebral signature for pain perception and its modulation. Neuron 55, 377–391 (2007).

77.Drossman, D. A. Beyond tricyclics: new ideas for treating patients with painful andrefractory functional gastrointestinal symptoms. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 104, 2897–2902 (2009).

78.Morgan, V., Pickens, D., Gautam, S., Kessler, R. & Mertz, H.Amitriptyline reduces rectal pain related activation of the anterior cingulatecortex in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gut 54, 601–607 (2005).

79.Perera, T. D., Park, S. & Nemirovskaya, Y. Cognitive role ofneurogenesis in depression and antidepressant treatment. Neuroscientist 14, 326–338 (2008).

80.Bremner, J. D. Does stress damage the brain? Biol. Psychiatry 45, 797–805 (1999).

81.Blankstein, U., Chen, J., Diamant, N. E. & Davis, K. D. Alteredbrain structure in irritable bowel syndrome: potential contributions ofpre-existing and disease- driven factors. Gastroenterology 138, 1783–1789 (2010).

82.Brunoni, A. R., Lopes, M. & Fregni, F. A systematic review andmeta-analysis of clinical studies on major depression and BDNF levels:implications for the role of neuroplasticity in depression. Int. J.Neuropsychopharmacol. 11,1169–1180 (2008).

83.Geddes, J. R. et al. Relapse prevention with antidepressant drugtreatment in depressive disorders: a systematic review. Lancet 361, 653–661 (2003).

84.Hansen, R. et al. Meta-analysis of major depressive disorder relapseand recurrence with second- generation antidepressants. Psychiatr. Serv. 59, 1121–1130 (2008).

85.Dekel, R., Drossman, D. A. & Sperber, A. D. The use ofpsychotropic drugs in irritable bowel syndrome. Expert. Opin. Investig.Drugs 22, 329–339 (2013).

86.Bomholt, S. F., Mikkelsen, J. D. & Blackburn-Munro, G.Antinociceptive effects of the antidepressants amitriptyline, duloxetine,mirtazapine and citalopram in animal models of acute, persistent andneuropathic pain. Neuropharmacology 48, 252–263 (2005).

87.Thoua, N. M. et al. Amitriptyline modifies the visceralhypersensitivity response to acute stress in the irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment.Pharmacol. Ther. 29, 552–560(2009).

88.Gorard, D. A., Libby, G. W. & Farthing, M. J. Influence ofantidepressants on whole gut and orocaecal transit times in health andirritable bowel syndrome. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 8, 159–166 (1994).

89.MIMS Australia. Monthly Index of Medical Specialties Australia. http://www.mims.com.au/ (2019).

90.Clouse, R. E. & Lustman, P. J. Use of psychopharmaco- logicalagents for functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gut 54, 1332–1341 (2005).

91.Ford, A. C. et al. Effect of antidepressants and psychologicaltherapies, including hypnotherapy, in irritable bowel syndrome: systematicreview and meta-analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 109, 1350–1365 quiz 1366; (2014).

92.Ford, A. C. et al. Efficacy of psychotropic drugs in functionaldyspepsia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut 66, 411–420 (2017).

93.Rahimi, R., Nikfar, S., Rezaie, A. & Abdollahi, M. Efficacy oftricyclic antidepressants in irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis. WorldJ. Gastroenterol. 15,1548–1553 (2009).

94.Ruepert, L. et al. Bulking agents, antispasmodics and antidepressantsfor the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011, CD003460 (2011).

95.Varia, I. et al. Randomized trial of sertraline in patients withunexplained chest pain of noncardiac origin.Am. Heart J. 140, 367–372 (2000).

96.Saarto, T. & Wiffen, P. J. Antidepressants for neuropathic pain. CochraneDatabase Syst. Rev. 2007,CD005454 (2007).

97.Brennan, B. P. et al. Duloxetine in the treatment of irritable bowelsyndrome: an open-label pilot study. Hum. Psychopharmacol. 24, 423–428 (2009).

98.Kaplan, A., Franzen, M. D., Nickell, P. V., Ransom, D. & Lebovitz,P. J. An open-label trial of duloxetine in patients with irritable bowelsyndrome and comorbid generalized anxiety disorder. Int. J. Psychiatry Clin. Pract. 18, 11–15 (2014).

99.Lewis-Fernandez, R. et al. An open-label pilot study of duloxetine in patients withirritable bowel syndrome and comorbid major depressive disorder. J. Clin.Psychopharmacol. 36, 710–715(2016).

100.Tack, J. et al. Efficacy ofmirtazapine in patients with functional dyspepsia and weight loss.Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 14, 385–392.e4 (2016).

101.Spiegel, D. R. & Kolb, R.Treatment of irritable bowel syndrome with comorbid anxiety symptoms withmirtazapine. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 34, 36–38 (2011).

102.Sohn, W. et al. Tianeptine vsamitriptyline for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea: amulticenter, open-label, non-inferiority, randomized controlled study. Neurogastroenterol.Motil. 24, 860–e398 (2012).

103.Patel, A. et al. Effects ofdisturbed sleep on gastrointestinal and somatic pain symptoms in irritablebowel syndrome. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 44, 246–258 (2016).

104.Kuiken, S. D., Tytgat, G. N. &Boeckxstaens, G. E. The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor fluoxetine doesnot change rectal sensitivity and symptomsin patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a double blind, randomized,placebo-controlledstudy.Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 1, 219–228 (2003).

105. Siproudhis, L.,Dinasquet, M., Sebille, V., Reymann, J. M. & Bellissant, E. Differentialeffects of two types of

antidepressants, amitriptyline and fluoxetine,on anorectal motility and visceral perception. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 20, 689–695 (2004).

106.Gorard, D. A., Libby, G. W. &Farthing, M. J. Effect of a tricyclic antidepressant on small intestinalmotility in health and diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Dig.Dis. Sci. 40, 86–95 (1995).

107.Thiwan, S. et al. Not all sideeffects associated with tricyclic antidepressant therapy are true side effects.Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 7,446–451 (2009).

108.Yuan, Y., Tsoi, K. & Hunt, R.H. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and risk of upper GI bleeding:confusion or confounding? Am. J. Med. 119, 719–727 (2006).

109.Wang, S. M. et al. Addressing theside effects of contemporary antidepressant drugs: a computer review. Chonnam.Med. J. 54, 101–112 (2018).

110.Foong, A. L., Grindrod, K. A.,Patel, T. & Kellar, J. Demystifying serotonin syndrome (or serotonin toxicity).Can. Fam. Physician. 64,720–727 (2018).

111.Sansone, R. A. & Sansone, L.A. Tramadol: seizures, serotonin syndrome, and coadministered antidepressants. Psychiatry6, 17–21 (2009).

112.Fava, G. A. et al. Withdrawalsymptoms after serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor discontinuation:systematic review. Psychother. Psychosom. 87, 195–203 (2018).

113.Fava, G. A., Gatti, A., Belaise,C., Guidi, J. & Offidani, E. Withdrawal symptoms after selective serotoninreuptake inhibitor discontinuation: a systematic review. Psychother.Psychosom. 84, 72–81 (2015).

114.Fuller-Thomson, E. & Sulman,J. Depression and inflammatory bowel disease: findings from two nationallyrepresentative Canadian surveys. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 12, 697–707 (2006).

115.Haapamaki, J. et al. Medicationuse among inflammatory bowel disease patients: excessive consumption ofantidepressants and analgesics. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 48, 42–50 (2013).

116.Mikocka-Walus, A. A., Gordon, A.L., Stewart, B. J. & Andrews, J. M. The role of antidepressants in themanagement of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): a short report on a clinicalcase-note audit.J. Psychosom. Res. 72, 165–167 (2012).

117.Mikocka-Walus,A. et al. Adjuvant therapy withantidepressants for the management ofinflammatory bowel disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, CD012680 (2019).

118.Mikocka-Walus, A. A. et al.Antidepressants and inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review. Clin.Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health 2,24 (2006).

119.Macer, B. J., Prady, S. L. &Mikocka-Walus, A. Antidepressants in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematicreview. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 23,534–550 (2017).

120.Tarricone, I. et al. Prevalenceand effectivenessof psychiatric treatments for patientswith IBD:a systematic literature review. J.Psychosom. Res. 101, 68–95(2017).

121.Thorkelson, G., Bielefeldt, K.& Szigethy, E. Empirically supported use of psychiatric medications inadolescents and adults with IBD. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 22, 1509–1522 (2016).

122.Chojnacki, C. et al. Evaluation ofthe influence of tianeptine on the psychosomatic status of patients withulcerative colitis in remission. Pol. Merkur. Lekarski 31, 92–96 (2011).

123.Daghaghzadeh, H. et al. Efficacyof duloxetine add on in treatment of inflammatory bowel disease patients: adouble-blind controlled study. J. Res. Med. Sci. 20, 595–601 (2015).

124.Mikocka-Walus, A. et al.Fluoxetine for maintenance of remission and to improve quality of life inpatients with Crohn’s disease: a pilot randomized placebo-controlled trial. J.Crohns. Colitis. 11, 509–514(2017).

125.Kristensen, M. S. et al. Theinfluence of antidepressants on the disease course among patients with Crohn’sdisease and ulcerative colitis — a Danish nationwide register-based cohortstudy. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 25,886–893 (2018).

126.Frolkis, A. D. et al. Depressionincreases the risk of inflammatory bowel disease, which may be mitigated by theuse of antidepressants in the treatment of depression. Gut 68, 1606–1612 (2018).

127.Hall, B. J., Hamlin, P. J.,Gracie, D. J. & Ford, A. C. The effect of antidepressants on the course ofinflammatory bowel disease. Can. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 2047242 (2018).

128.Goodhand, J. R. et al. Doantidepressants influence the disease course in inflammatory bowel disease? Aretrospective case-matched observational study. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 18, 1232–1239 (2012).

129.Halpin, S. J. & Ford, A. C.Prevalence of symptoms meeting criteria for irritable bowel syndrome ininflammatory bowel disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J.Gastroenterol. 107,1474–1482 (2012).

130.Henriksen, M., Hoivik, M. L.,Jelsness-Jorgensen, L. P. & Moum, B. Irritable bowel-like symptoms inulcerative colitis are as common in patients in deep remission as ininflammation: results from a population-based study (the IBSEN study). J.Crohns. Colitis. 12, 389–393(2018).

131.Iskandar, H. N. et al. Tricyclicantidepressants for management of residual symptoms in inflammatory boweldisease. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 48,423–429 (2014).

132.Morrison, G., Van Langenberg, D.R., Gibson, S. J.& Gibson, P. R. Chronic pain ininflammatory bowel disease: characteristics and associations of a hospital-based cohort. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 19, 1210–1217 (2013).

133.Long, M. D., Barnes, E. L.,Herfarth, H. H. & Drossman, D. A. Narcotic use for inflammatory boweldisease and risk factors during hospitalization. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 18, 869–876 (2012).

134.Zeitz, J. et al. Pain in IBDpatients: very frequent and frequently insufficiently taken into account. PLoSOne 11, e0156666 (2016).

135.Farrell, K. E., Keely, S., Graham,B. A., Callister, R. & Callister, R. J. A systematic review of the evidencefor central nervous system plasticity in animal models of inflammatory-mediatedgastrointestinal pain. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 20, 176–195 (2014).

136.van Hoboken, E. A. et al. Symptomsin patientswith ulcerative colitis in remissionare associated with visceral hypersensitivity and mast cell activity.Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 46, 981–987 (2011).

137.Coates, M. D. et al. Abdominalpain in ulcerative colitis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 19, 2207–2214 (2013).

138.Long, M. D. & Drossman, D. A.Inflammatory bowel disease, irritable bowel syndrome, or what? A challenge tothe functional-organic dichotomy. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 105, 1796–1798 (2010).

139.Swanson, G. R. & Burgess, H.J. Sleep and circadian hygiene and inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol.Clin. North. Am. 46, 881–893(2017).

140.Ananthakrishnan, A. N., Long, M.D., Martin, C. F., Sandler, R. S. & Kappelman, M. D. Sleep disturbance andrisk of active disease in patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 11,965–971 (2013).

141.Wichniak, A., Wierzbicka, A.,Walecka, M. & Jernajczyk, W. Effects of antidepressants on sleep. Curr.Psychiatry Rep. 19, 63(2017).

142.Melo, F. L. et al. What doCochrane systematic reviews say about interventions for insomnia? Sao PauloMed. J. 136, 579–585 (2018).

143.Jansson-Frojmark, M. &Norell-Clarke, A. The cognitive treatment components and therapies of cognitivebehavioral therapy for insomnia: a systematic review. Sleep. Med. Rev. 42, 19–36 (2018).

144.Trauer, J. M., Qian, M. Y., Doyle,J. S., Rajaratnam, S. M. & Cunnington, D. Cognitive behavioral therapyfor chronic insomnia: a systematicreview and meta-analysis. Ann. Intern. Med. 163, 191–204 (2015).

145.Varghese, A. K. et al.Antidepressants attenuate increased susceptibility to colitis in a murine modelof depression. Gastroenterology 130,1743–1753 (2006).

146.Guemei, A. A., El Din, N. M., Baraka,A. M. & El Said Darwish, I. Do desipramine[10,11-dihydro-5- [3-(methylamino) propyl]-5H-dibenz[b,f]azepinemonohydrochloride] and fluoxetine [N-methyl-3-phenyl-3-[4-(trifluoromethyl)phenoxy]-propan-1- amine] ameliorate the extent ofcolonic damage induced by acetic acid in rats? J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 327, 846–850 (2008).

147.Arnone, D. et al. Role ofkynurenine pathway and its metabolites in mood disorders: a systematic reviewand meta-analysis of clinical studies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 92, 477–485 (2018).

148.Miller, A. H. & Raison, C. L.The role of inflammation in depression: from evolutionary imperative to moderntreatment target. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 16, 22–34 (2016).

149.Sforzini, L., Nettis, M. A.,Mondelli, V. & Pariante, C. M. Inflammation in cancer and depression: astarring role for the kynurenine pathway. Psychopharmacology236, 2997–3011 (2019).

150.Timmer, C. J., Sitsen, J. M. &Delbressine, L. P. Clinical pharmacokinetics of mirtazapine. Clin.Pharmacokinet. 38, 461–474(2000).

151.Laird, K. T., Tanner-Smith, E. E.,Russell, A. C., Hollon, S. D. & Walker, L. S. Comparative efficacy ofpsychological therapies for improving mental health and daily functioning inirritable bowel syndrome:a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 51, 142–152 (2017).

152.Thiwan, S. I. & Drossman, D.A. Treatment of functional GI disorders with psychotropic medicines: a reviewof evidence with a practical approach. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2, 678–688 (2006).

153.Gracie, D. J. et al. Effect ofpsychological therapy on disease activity, psychological comorbidity, andquality of life in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review andmeta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2, 189–199 (2017).

原文来源:

Mikocka-Walus A,Ford AC,Drossman DA.Antidepressants in inflammatory bowel disease.Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol.2020;17(3):184–192. doi:10.1038/s41575-019-0259-y

作者|Antonina Mikocka-Walus,Alexander C. Ford,Douglas A. Drossman

编译|张砚宁

审校|617