编者按:

《美国胃肠病学杂志》是由美国胃肠病学会出版的一本涵盖胃肠病学和肝病学的临床期刊,它为解决胃肠病学疾病提供了实用和专业的支持。

今年,该杂志对 2010~2019 年这十年间胃肠病学和肝病学的主要趋势做了重要的回顾。今天,我们特别编译了这篇文章,希望本文能够为相关的产业人士和诸位读者带来一些启发与帮助。

一个新的十年又到来了。在上一个十年里,医疗保健领域发生了巨大的变化,而接下来持续发生的变化,会不可避免地影响到胃肠病学和肝病学的医疗实践。

有时,我们会非常关注当前或未来的发展,而轻易地遗忘过去。然而,我们相信现在的关键是,在开始下一个十年的研究和创新之前,先短暂地暂停一下,回首反思一下 2010 年到 2019 年胃肠病学和肝病学的一些重要进展。

这篇文章首次发表于《美国胃肠病学杂志》。它是由该杂志的副编辑们撰写的,他们是各自领域公认的专家。他们回顾了过去十年的科学文献,以确定 8 个主要关注的领域(内窥镜、食道、结直肠、小肠、肠-脑互作障碍、肝病学、胰腺病学和炎症性肠病)的主要趋势、发展、创新和改变实践的想法。

本篇综述中总结及引用的主要文章来自世界各地的胃肠病学和肝病学杂志,并不是专门从《美国胃肠病学杂志》中选取的文章。

此外,由于 COVID-19 大流行始于2020年,本篇综述将不对该疾病的研究进行讨论。我们知道,你们将从本篇综述中获益,我们衷心地希望,你们像我们一样,能在回顾过去十年成就的过程中得到充分的享受。

在过去的十年里,内镜手术的三个主要主题,包括介入性超声内镜(EUS)功能的进展,涉及黏膜下或“第三”空间的治疗手段的激增,以及对再处理的十二指肠镜所传播的感染的潜在识别。

介入性超声内镜

在过去的十年里,介入性超声内镜的医疗实践发生了天翻地覆的变化。其主要进展之一是腔内贴壁金属支架(LAMS)的应用——首次用于体外常温实验研究中。

LAMS 最初的设计是为了使非粘附性的肠外积液经腔内引流1。2013 年,它被美国食品药品管理局(FDA)批准,可以用于假性囊肿引流2;2017 年,AXIOS 支架和电灼增强递送系统被 FDA 批准,可以在胰腺假性囊肿大小≥6 cm或包裹性坏死≥6 cm 时,用于经胃或十二指肠内镜下引流3。

在过去的几年中, 因为该技术可以真正做到腔内贴壁,所以其临床应用已经大大扩展,革新了介入性超声内镜的引导手段。

根据临床研究数据,它的临床应用已经从胰腺假性囊肿引流扩展到了胆囊引流4、胆管引流5、胃肠造口术6,以及在 Roux-en-Y 手术中将经胃瘘管置入被切除的胃组织中7。后一种应用使得内镜医师可以利用LAMS,对那些在解剖结构上具有挑战性的患者进行经内镜逆行胰胆管造影和介入性超声内镜操作。

第三空间内镜/黏膜下内镜

常规的消化道内镜检查包括:食道、胃、十二指肠镜,结肠镜和小肠镜。消化道的腔内被认为是初级或第一空间。过去 20 年的设备和技术的优化,使得内镜医师能够进入第二空间(腹膜腔),而近 10 年,内镜医师已能够进入第三空间(黏膜下空间)。

第三空间内镜的主要关注点是确保进入黏膜下层的入口安全闭合。2007 年,黏膜瓣安全阀(SEMF)技术的引入,使得内镜医师可以利用黏膜瓣成功封堵缺口8,安全地检查第二和第三空间。SEMF 技术的有效性,首次在 2007 年的一项动物内镜下肌切开术研究中得到证实9。

此后,黏膜下内镜被用于各种胃肠疾病,包括用于治疗贲门失弛缓症的经口内镜下肌切开术(POEM)10,用于治疗粘膜下肿瘤的经内镜下隧道黏膜下肿瘤切除术11,用于治疗胃轻瘫的胃POEM12,用于治疗 Zenker 憩室的内镜经黏膜下隧道憩室中隔离断术(Z-POEM)13。

许多研究显示,该技术在 POEM14-17、经内镜下隧道黏膜下肿瘤切除术18-20、胃 POEM21-23和 Z-POEM24,25中都有很好的疗效。

内镜黏膜下剥离术,于 1988 年首次被描述为一种切除早期胃肿瘤的内镜技术26。因为这项技术既切除了黏膜又切除了黏膜层,所以应被归入黏膜下内镜技术。但是,它却没有用到 SEMF 技术。

内镜黏膜下剥离术是一个值得提及的进步,因为它已经从一个不常见的实验技术,迅速发展为一项用于内镜下整体切除胃肠道上皮病变部位的常规手段27。

十二指肠镜传播的感染

在过去的十年里,无数的报告报道了,在经内镜逆行性胰胆管造影中,因为十二指肠镜而导致多重耐药菌的传播,特别是抗碳青霉烯类肠杆菌28-31。

这些事件导致 FDA 强制要求加强十二指肠镜的再处理技术,包括双重高水平消毒、环氧乙烷灭菌、再处理后将试剂收集培养,以及液体化学灭菌技术的使用32。然而,上述技术到底有多少效用仍是未知数33,34。

FDA 的监测研究发现,高达 6.1%的经过完全再处理过的十二指肠镜上,出现了需要“高度关注”的细菌35。这些结果使得 FDA 建议医疗机构,从使用固定端盖的十二指肠镜,过渡到使用设计新颖的十二指肠镜,新型十二指肠镜包含一次性组件,可优化或无需再处理36。

最近,科学家们已经研发出了一次性使用的十二指肠镜,并且在积极评估它们的作用37,38。未来在这方面的进展,可能包括验证适当再处理步骤的更好手段,以及新的灭菌技术,包括低温再处理。

21 世纪 10 年代,食管疾病的评估和治疗发生了重大变化。而在这十年中,对质子泵抑制剂(PPI)过度使用的担忧,挑战了“长期使用 PPI 是安全”的信条。在整个 21 世纪 10 年代中,几乎持续不断的研究报告称,PPI 的使用与一系列潜在副作用之间存在微弱联系,包括胃肠道癌症39。

这促使医生对许多患者停用 PPI,甚至是那些有胃酸消化性并发症的高危患者,并鼓励患者在不咨询提供者的情况下自行停用 PPI。尽管胃肠病学会发布了一系列出版物40-42,旨在阻止这类潜在危险行为,但这些行为还是发生了。

而在这十年即将结束时,第一个大规模随机试验证实,除了肠道感染轻微增加(使用 PPI 三年的感染率为 1.4%,对照为 1.0%)以外,PPI 没有其他所谓的不良反应42。

21 世纪 10 年代结束时,针对治疗胃酸消化性疾病,出现了一种新的治疗方案——钾离子竞争性酸阻滞剂。该治疗方案起效更快,并且在剂量依赖和非膳食依赖的胃酸抑制方面,至少与 PPI 同样有效43。

在胃酸消化性疾病领域,病理性食管胃酸暴露时间,被视为食管反流监测的关键指标,可用于预测胃食管反流病(GERD)的治疗转归44,并为其诊断提供确凿证据45。

对于 pH-阻抗监测,在夜间测定的基线阻抗值(平均夜间基线阻抗),以及测定的清除与中和反流胃酸的主要蠕动波频率(反流后吞咽引起的蠕动波指数),被作为可以预测 GERD 转归的客观评估指标46–48。

现在,可以使用一种新的设备来测定基线阻抗,这种设备最初是为用于清醒镇静内镜检查而开发的,它是一个装有两排阻抗传感器的食管球囊49,50。

关于 GERD 诊断依据的客观共识标准已经发表了45。

测试证实,非反流病因的食管症状患者,比确诊为 GERD 但对 PPI 无反应的患者人数更多51,并且当对确诊为 GERD 的患者进行有针对性的反流治疗时,治疗效果更好44,51-53。因此,在过去的十年中,临床医生的诊断设备不断发展,使得对 GERD 的诊断更加精确。

在治疗方面,人们一直在对 PPI 疗法的替代疗法进行评估:其中,括约肌磁性增强54,55和经口无切口胃底折叠术56尤为突出,它们都显示出了对特定患者的短期和中期疗效。

21 世纪初期,巴雷特食管和早期食管肿瘤的内镜疗法的出现,在 21 世纪 10 年代引发了一场治疗革命。治疗的指导方针从建议对轻度异型增生进行监测,转向考虑内镜治疗;从对重度异型增生的监测或进行食管切除术,转向内镜治疗;从对 T1a 期的食管腺癌进行食管切除术,转向内镜治疗57。

2018 年出版的“阿斯匹林和埃索美拉唑在巴雷特食管化生试验中的化学预防作用”表明,在该随机试验中,与不服用阿司匹林和每日服用一次 20 mg 埃索美拉唑的患者相比,服用阿司匹林和每日两次 40 mg 埃索美拉唑的患者,进展到重度异型增生、癌变或死亡的综合转归减少了58。

在过去的十年中,我们发现消化性溃疡疾病和幽门螺杆菌感染的发病率有所下降,这主要归因于抗生素和 PPI 疗法的优化。

一项系统性综述显示,对于幽门螺旋杆菌感染而言,为期 5 天或 10 天的伴同疗法优于为期 5 天、7 天或 10 天的 PPI-阿莫西林-克拉霉素的三联疗法,但不优于为期 14 天的三联疗法59。到 2019 年,这种感染的发病率已经从 11%下降到了 9%60。

肠化生在临床实践中仍然是一个重要的问题,尤其是对胃癌的发展而言。研究人员已经确定了几个肠化生的危险因素,包括高龄、男性、非白种人、种族因素和吸烟61。

通过胃镜对胃黏膜进行分级,仍是早期胃癌鉴别的重要决定性因素。在根除幽门螺杆菌感染的患者中,胃黏膜萎缩被认为是胃癌发展的关键危险因素62。

在过去的十年里,我们已经看到,越来越多的人意识到嗜酸性肠病是一个重要的临床问题。嗜酸性肠病与许多因素有关,包括饮食、微生物组和其他生活方式63。

对于嗜酸性食管炎(EoE),PPI 应答者与 PPI 无应答者具有相似的人口统计、临床和分子特征,这促使指南将 PPI 无反应,从 EoE 的诊断标准中剔除出去64–67。

用过敏试验(皮肤点刺试验、斑贴试验或血清过敏原检测)来确定 EoE 的致病食物,已被证明是不够准确的67。多中心、随机、对照试验评估了专为 EoE 特制的外用类固醇和生物制剂的临床转归,在未来十年中,这两种选项可作为治疗 EoE 的药物方案68-72。

新版芝加哥分类标准进一步强调,将高分辨率测压(HRM)作为反映食管运动障碍的特征73。

辅助性 HRM 增强动作(多次快速吞咽、快速饮水挑战和标准化试验餐)和辅助试验(功能性管腔成像探头)的作用已进一步确立:避免使用现有的 HRM 方案,而造成对食管运动障碍的过度诊断和诊断不足74。

针对收缩异常的食管平滑肌和不松弛的食管下括约肌而进行的 POME,是一种具有良好症状预后的小切口手术,尽管接受这种手术的患者中,大约一半有发生胃酸反流的风险75。

在过去十年中,结直肠疾病领域的进展涵盖了一系列主题,从中规中矩且常见的(提高结直肠镜前准备的效率)到更前沿但不常见的(评估微卫星的不稳定性)。以下章节简要介绍了其中一些关键进展。

结肠镜检查前准备

在结肠镜检查之前进行有效的镜前准备,对于结肠息肉和结直肠肿瘤的检测至关重要。它也成为衡量结肠镜检查质量高低的重要指标76,77。不遵循给药指导进行镜前准备,已被证明是结肠镜检查前准备不理想的有力预测因子(优势比[OR],6.7;95%置信区间[CI],3.2–14.2)78。

一项对接受常规筛检结肠镜的平均风险患者的分析显示,镜前准备不良的患者中,有 86.7%没有完成镜前准备,或没有遵循书面说明的准备时间或饮食限制进行镜前准备79。

肠道准备制剂分 2 次给药,并在结肠镜检查的当天摄入 50%以上,在疗效和耐受性上被认为优于在检查前一天单次给药80,81。

一项针对 5 项随机试验的荟萃分析报告称,与检查前一天单次给药相比,对 4 L 聚乙二醇溶液进行两次给药,增加了镜前准备充分的患者数量(OR 3.7;95%CI,2.8-4.9),并增强了患者为后续结肠镜检查进行再次准备的意愿(OR 1.8;95%CI,1.1-2.9),同时减少了恶心的发生率(OR 0.6;95%CI,0.4-0.8)(82)。

另一项针对 15 项随机试验的荟萃分析也支持了在检查当天进行镜前准备的有效性,这些研究记录了,与两次给药相比,在检查当天进行镜前准备,有着相似的准备质量(相对风险[RR],0.95,95%CI,0.90-1.00),腺瘤检出率(ADR;RR,0.97;95%CI,0.79-1.20)和患者重复该过程的意愿(RR,1.14;95%CI,0.96–1.36)83。

此外,对于当天晚些时候安排的结肠镜检查而言,镜前准备不理想的可能性有所增加(OR,1.9;95%CI,1.7-2.1)84,这可能是镜前准备和手术之间的间隔时间较长造成的。

一项对连续 378 名门诊患者的前瞻性分析发现,在最后一次镜前准备给药和开始结肠镜检查之间,每等待一小时,患者镜前准备质量评级为良好或优秀的可能性下降近 10%85。因此,较短的间隔时间,可能会增加良好或优秀的镜前准备的比率,而这反过来又可能会提高结直肠肿瘤的检出率。

最近的指南强烈建议镜前准备应两次给药,当天给药可作为两次给药的替代方案,特别是对于安排在下午进行结肠镜检查的患者,最后一次镜前准备给药在手术前 4~6 小时开始,在手术至少 2 小时前完成80。

结肠癌及其预防方面的最新进展

在过去的十年里,我们对结直肠癌(CRC)和遗传综合征的家族倾向的理解,有了显著的进展86。有CRC家族史的人,患有 CRC 的风险增加。风险增加的程度取决于患有 CRC 亲属的数量、亲缘关系的远近(一级亲属或二级亲属)以及亲属被诊断患有 CRC 时的年龄87-89。

最近的研究表明,大约 10%~15%的 CRC 患者存在高外显率和中等外显率的的致病性癌症易感基因。为了诊断这些高风险患者,医疗机构已经开始广泛采用“通用”肿瘤筛查方法,这种方法利用微卫星不稳定性和/或免疫组化,来显示错配修复蛋白(MLH1、MSH2、MSH6 和 PMS2)的表达缺陷,以确定最有可能患 Lynch 综合征的结直肠癌或子宫内膜癌患者。

技术的进步(下一代测序),以及检测实验室数量的增加,使得大众能够负担得起这种筛查(不到 500 美元)。

现在,我们可以同时检测几十个基因,从而对多种癌症类型的遗传易感性进行全面检测。

此外,与 CRC 基因组相关的精准治疗选择也在增加。例如,对于患有 CRC 和 Lynch 综合征错配修复基因致病性突变的患者而言,他们的治疗方案是最具特色的,其个性化疗法包括免疫检查点抑制剂93。

在过去的十年里,类癌的术语发生了变化,它们被重新命名为神经内分泌肿瘤(NETs)。在过去的十年中,NETs 的识别率得到了提高,部分原因是成像技术的改进,如 DOTA-octreotate、oxodotrotide、DOTA-(Tyr3)-octreotate 和 DOTA-0-Tyr3-Octreotate 镓 68 正电子发射断层摄影术/计算机断层摄影术。

在英格兰,每年的 NETs 总发病率从十万分之 0.27 上升到十万分之 1.3294。

治疗 NETs 方面的改进,包括使用已被证明具有强大抗肿瘤作用的兰瑞肽95,以及最近批准的 telotristat96,还有利用 177Lut-DOTA-octreotate、oxodotreotide、DOTA-(Tyr3)- octreotate 和 DOTA-0-Tyr3-Octreotate,来进行以生长抑素受体为基础的肽受体放射性核素治疗97。

直肠是 NETs 的第三大高发部位,在直肠的 NETs 大约 80%是直径较小的(<1cm),可以通过内镜进行治疗98。

另一个关键进展是对高质量结肠镜检查的重视,包括监测关键质量指标,如 ADR 和改善镜前准备99。结肠镜筛查的 ADR 目标已提高到了 30%99。

通过提高内镜医师的技术(改变病人体位、水交换操作和近端结肠的二次检查)、改进内镜设备(高倍镜、辅助设备如 Endocuff、Endocap 和 Endorings,以及人工智能软件的应用)、对内镜医师进行培训以及定期绩效评估,提高了结肠镜检查的有效性100,101。

乳糜泻

在过去的十年中,我们对于乳糜泻流行病学的理解不断发展。过去的研究发现,在美国,只有不到 20%的乳糜泻患者能够被确诊102。然而,国家健康和营养调查(2013-2014)的最新数据发现,现在,超过 50%的乳糜泻患者有了明确的诊断,这表明疾病意识和检测水平有所提高103。

有趣的是,尽管美国人群中乳糜泻的患病率为 0.7%104,但采用无谷蛋白饮食(GFD)的非乳糜泻患者增长的却很快(无论是由于非乳糜泻谷蛋白敏感、肠易激综合征 IBS 还是作为一种未经证实的健康策略),目前报道有近 2%的美国人采用 GFD101。

尽管缺乏强有力的证据以证明 GFD 可以改善许多非谷蛋白相关肠病患者的临床转归,但这种增长仍然发生了。

乳糜泻的预防策略,主要在于婴儿期引入谷蛋白的时间。2014 年,两项随机试验以 6 个月为对照,测试了早期(4 个月)或晚期(12 个月)引入谷蛋白的方法。以上两种方法都没有降低患乳糜泻的风险105,106。

在这些阴性试验之后,队列研究和病例对照研究发现,在生命早期的前 2 年中,摄入的谷蛋白越多,与乳糜泻的风险适度增加有关,这表明谷蛋白的摄入量(而不是其引入的时间)可能是关键因素,因此值得未来更多地研究107。

近年来,GFD 的治疗负担已经有所记录,乳糜泻患者自我报告称,比糖尿病或充血性心力衰竭患者的治疗负担更重108。造成这种治疗困难的部分原因,是由于加工食品的无谷蛋白状态(以及安全性)的不确定性。

一项对便携式谷蛋白检测设备的众包分析发现,餐馆里声称无谷蛋白的披萨和面食实际上常常存在谷蛋白污染109。

这种治疗负担,促使医疗人员努力研发非饮食疗法,来治疗乳糜泻。除了改变现有药物的使用方法(如打开布地奈德胶囊,只服用内容药物,来治疗难治性乳糜泻)110,非饮食疗法还包括各个临床发展阶段的药物,包括紧密连接调节剂111、谷蛋白降解疗法112和肽诱导耐受疗法113。

短肠综合征

肠道生长因子在短肠综合征(SBS)患者中的应用引起了人们极大的兴趣,尽管优化了这些患者的饮食和医疗管理,但他们仍无法依靠自己的肠道,独立地生活。

替度鲁肽是一种重组、抗降解、长效胰高血糖素样肽 2(GLP-2)类似物,具有良好的安全性和耐受性,与安慰剂组相比,接受替度鲁肽治疗的患者,应答评分提高了一倍(63% vs 30%,P=0.002)。

此外,接受替度鲁肽治疗的患者中,有 54%能够减少至少每天/周一次的肠外营养(PN)输注,相比之下,安慰剂组为 23%114。

一项开放标签的长期延伸研究表明,持续使用替度鲁肽,可持续改善 PN 的戒断情况115。最近,一项为期 24 周的 III 期随机双盲安慰剂对照试验显示,替度鲁肽可显著降低 SBS 患儿对肠外支持的需求116。替度鲁肽现在被批准用于成人和儿童 SBS 患者,作为 PN 戒断的辅助疗法。

科学家们正在研发其他长效 GLP-2 类似物,这些药物具有较低给药频率的潜在优势。而替度鲁肽的长期效益和风险、与 SBS 发病相关的给药时机、最佳的患者选择、治疗时间和成本效益,还需要进一步研究。

最近,在 SBS 治疗方面,人们也对 GLP-1 类似物产生了兴趣。在一项开放标签的初步研究中,给 8 例 SBS 空肠末端造口术患者,每日皮下注射利拉鲁肽,发现利拉鲁肽可减少造口处肠道内容物的湿重输出,增加患者的肠道湿重和能量吸收117。

科学家们正在探索 GLP-1 和 GLP-2 激动剂的联合应用对 SBS 的作用。在一项涉及瘦鼠和糖尿病小鼠的研究中,一种 GLP-1/GLP-2 共同激动剂显示出了增加肠道上皮体积和黏膜表面积的作用,并对小鼠血糖产生了有益影响118。

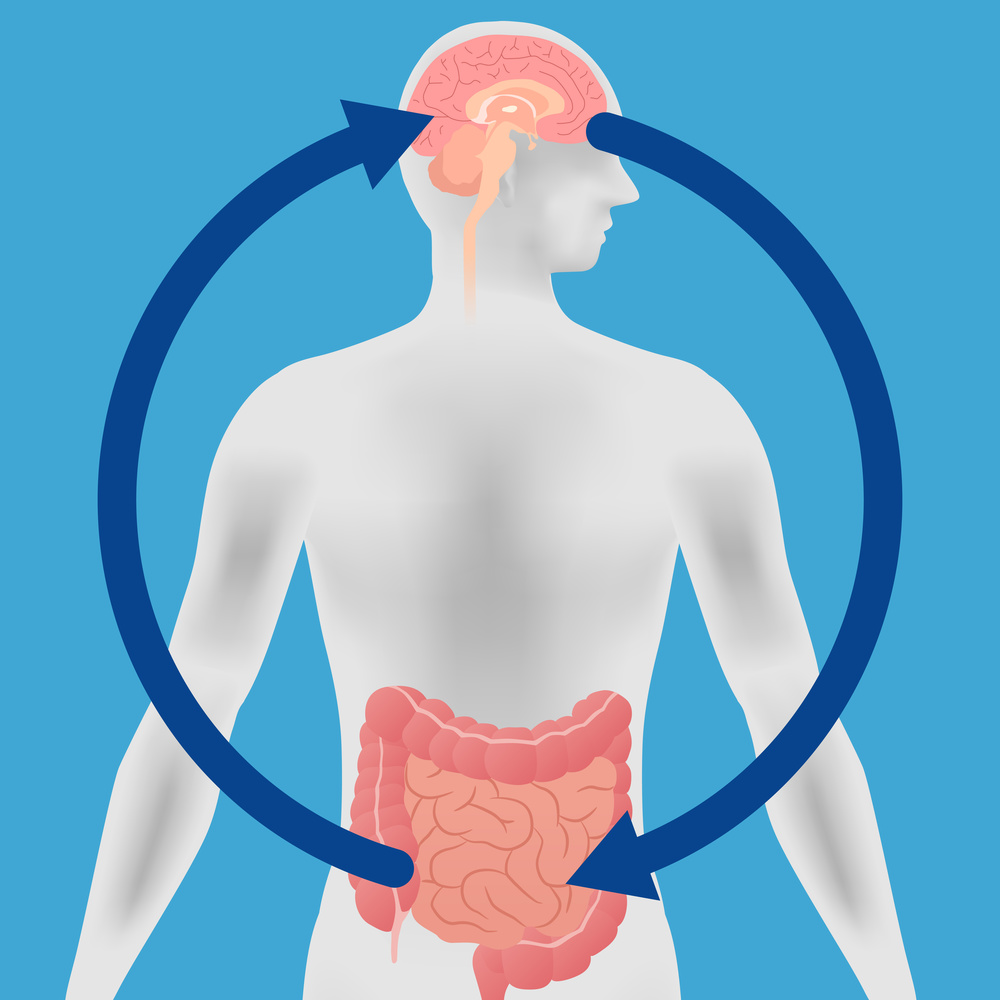

新定义与精神性胃肠病学

多年来,描述功能性胃肠疾病的术语五花八门。过去十年的一个重要进展,是将功能性胃肠疾病命名为肠-脑互作障碍119,它取代了不那么具体且可能带有歧义的术语“功能性”,并反映了发病机制的概念,这些概念是从脑成像120和其他显示肠和脑的因素累积影响 IBS 症状严重程度的研究中衍生出来的121。

以上这种概念的重新定义,强化了基本原理,使医疗人员将心理治疗常规纳入最佳实践中,加深了他们对于心理治疗的理解,并增加了合格和可获得的心理健康医疗人员的数量,还拓展了神经调质疗法122。

已有的数据表明,在无精神病理变化的情况下,认知行为疗法(CBT)可以为 IBS 患者提供长达一年的改善,但是这种治疗可能很难获得,因为接受过针对肠道的 CBT 模式训练的治疗师数量有限。

然而,治疗师提供的电话 CBT 和线上 CBT,可以提高 CBT 在儿童、青少年和成人中的可获得性,并且这种 CBT 也被证明是有效的123-125。

个体肠道定向催眠疗法也可以改善 IBS 症状,该疗法能够使内脏刺激的中枢处理异常正常化,进一步支持了这些患者的肠-脑互作的相关性126。当进行集体肠道定向催眠疗法时,IBS 的症状可以改善一年之久127。

对 IBS 传统疗法的系统性综述和网络荟萃分析表明,低剂量至中等剂量的三环类抗抑郁药是最受支持的中枢神经调质,适用于减轻中期慢性疼痛。其与相比较的其他疗法(可溶性纤维,抗痉挛药物)的益处相比,在减轻疼痛方面排名第一,在改善全身症状方面排名第二128。

肠道定向药物

在过去的十年里,新的药物疗法的激增,为医生和患者提供了更多的选择。

促胃肠动力药的回归。10 年来收集的数据显示,关于 5-HT4 激动剂相关心血管事件增加的说法有所减少。因此,在过去的一年里,FDA 再次批准了替加色罗,用于治疗 65 岁以下成年女性便秘型 IBS129。普卢卡必利被批准用于成人慢性特发性便秘130,它也可以改善胃轻瘫患者的症状131。

促分泌素。促分泌素是随着鸟苷酸环化酶 C 激动剂——利那洛肽132和普卡那肽133,以及钠氢交换蛋白-3 抑制剂——替纳帕诺134的出现而发展起来的。上述药物都被 FDA 批准用于治疗便秘型 IBS,前两种药物也被批准用于慢性特发性便秘。

一系列的临床研究证实,以上药物对 IBS 全身和局部症状有所改善。这些药物的作用机制已经阐明,而且每一种药物都比它的上一代药物(主要是非处方药)更具优势。

其他。艾沙度林是一种 FDA 批准的混合 μ-k 阿片受体激动剂以及 δ 受体拮抗剂,可减轻腹泻型 IBS 患者的全身疼痛和肠道症状。前瞻性研究也表明,艾沙度林对非处方洛哌丁胺135,136无应答的个体有效。

小肠释放型薄荷油可减轻 IBS 的疼痛137,在一项系统性综述和网络荟萃分析中,薄荷油在全身症状缓解方面排名第一128,但应注意的是,研究质量因治疗而异,这使得这样的直接比较存在难度。

超过 25%的腹泻型 IBS 患者,存在胆汁酸吸收障碍的情况138,尽管只有很少的确定性证据139,但医疗人员可以考虑使用胆甾胺进行治疗。

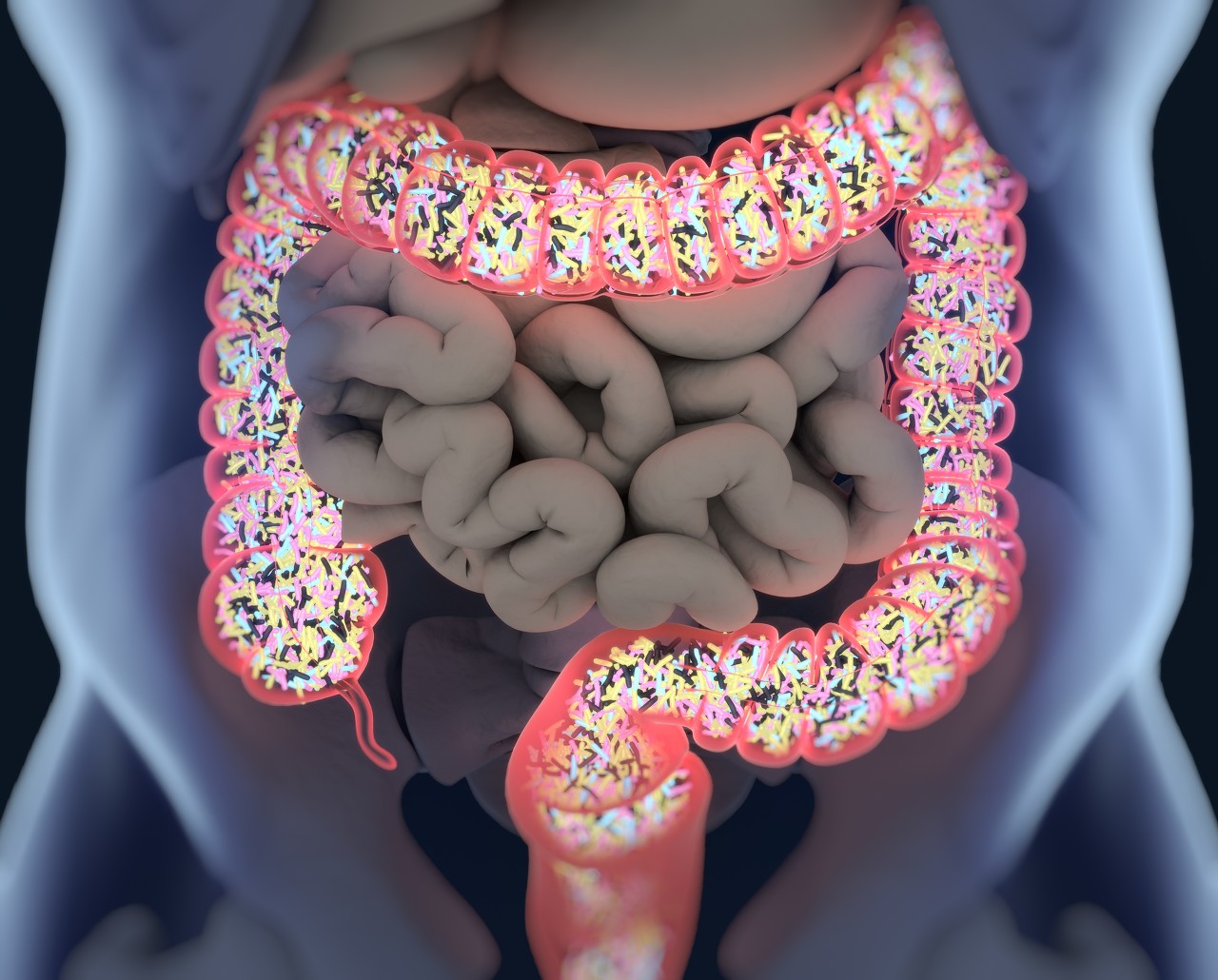

微生物组与治疗

肠道微生物组的变化,已被认为在肠-脑互作障碍的发病机制中起到了重要的作用,并且在过去的十年里,相关的研究已经显著增加。

在急性胃肠道感染后,约 10%的患者会出现符合 IBS140和功能性消化不良141诊断标准的持续症状。 IBS 与小肠微生物组的慢性改变(称为小肠细菌过度生长)之间的联系,继续引起人们的兴趣142。研究已经证实 IBS 患者粪便微生物组成发生改变,尽管研究结果在不同的研究中有所不同,不过这可能是由于 IBS 的异质性。尽管粪便样本的获取较为简单,但从其他部位(包括小肠黏膜)采集的微生物组,可以提供更多与临床相关的信息。

用非吸收性抗生素利福昔明靶向肠道微生物组,可显著改善 IBS 症状143,而且似乎可改善功能性消化不良144。然而,在治疗过程中,粪便微生物组只有轻微的、短暂的变化,这表明其作用是非抗生素的145。

益生菌可以改善 IBS,但改善最大的微生物物种和菌株仍不清楚146,147。

大脑结构和功能的关联与肠道微生物组148,149有关。随着益生菌治疗的实施,大脑激活区发生改变,并可改善抑郁和提高生活质量150。

粪菌移植在 IBS 中的应用已被研究,但迄今为止,结果尚未达到预期151。尽管一些数据表明粪菌移植可能有一定益处152,但想要在临床上推荐这种疗法作为常规方法用于治疗 IBS,还为时过早,虽然有人自行进行粪菌移植153。

饮食是影响肠道微生物组的一个重要外在因素,并且似乎在症状产生中起着关键作用。在过去的十年里,饮食研究主要集中在低可发酵低聚糖、双糖、单糖和多元醇(FODMAPs)饮食和 GFD 在减轻 IBS 症状方面的作用。

一些小型随机对照试验表明,低 FODMAP 饮食和 GFD 对 IBS 都是有益的;然而,最近的一项系统性综述和荟萃分析得出的结论是,没有足够的证据推荐 GFD 来减轻 IBS 症状,而低 FODMAP 饮食能有效减轻 IBS 患者症状的证据质量很低154。

丙型肝炎

谁能预料到,在 1989 年发现丙型肝炎病毒(HCV)后不到 30 年的时间,耐受性良好、病毒学治愈率高达 100%的疗法就出现了?

丙型肝炎最初被标记为非甲、非乙型肝炎,治疗时依次使用干扰素、干扰素和利巴韦林,然后再用聚乙二醇干扰素和利巴韦林治疗 48 周。感染基因 1 型(最常见的基因分型)丙肝病毒的患者,可获得 30%的持续病毒学应答(SVR)。

然而,这些成功造成了巨大的代价和副作用,包括流感样症状、抑郁和少量的自杀情况。

首批直接作用的抗病毒药之一——蛋白酶抑制剂 BILN2061,在动物研究中会造成心脏毒性,因此,人们虽然最初对它感到的很兴奋,但最终放弃了进一步的开发155。

直到 21 世纪 00 年代末,第一批蛋白酶抑制剂特拉匹韦和博赛泼维的随机临床试验才被公布,它们的 SVR 率达到了当时的最高纪录,大约 70%156,157。不过,这些蛋白酶抑制剂当时是与聚乙二醇干扰素和利巴韦林联用的,而蛋白酶抑制剂组的停药率是聚乙二醇干扰素和利巴韦林组的两倍。

下一个重大进展是从治疗方案中去除干扰素。2013 年,一项试验使用 NS5B-聚合酶抑制剂索非布韦,而不使用干扰素治疗丙型肝炎,该研究表明,不使用干扰素也可以实现较高的 SVR 率158。

第一个不使用干扰素的治疗方案包括使用不同种类的药物,一种聚合酶和一种蛋白酶,包括索非布韦和西咪匹韦。这种用药组合(COmbination)经常被称为 HCV 感染的西咪匹韦(SiMeprevir)和索非布韦(sOfoSbuvir)联合应用(COSMOS)方案,并且这种方案在感染基因1型丙肝病毒患者中显示出了优越的 90%的 SVR 率159。

尽管这种疗法很成功,但后来仍被其他疗法取代,部分原因是这些药物是由两家不同的制药公司生产的。

随后的进展集中在开发不包括利巴韦林的泛基因型治疗方案160-163。维帕他韦-索非布韦和格拉卡匹韦-哌仑他韦是两种不含利巴韦林的泛基因型药物方案,病毒学治愈率高达 100%,停药率仅 1%161,163。

维帕他韦-索非布韦还可用于失代偿期肝硬化患者,这是一个治疗难度极大的人群。

对于符合标准的患者,使用格拉卡匹韦-哌仑他韦可使治疗持续时间缩短至 8 周。重要的是,病毒学治愈与较低的肝脏相关和全因死亡率有关164。

酒精性肝病与肝移植

在年轻人中,酒精相关性肝病发病率正在迅速升高165。酒精性肝病的阴霾笼罩着酒精相关性肝病的死亡率统计数字。

酒精性肝炎患者容易发生感染、门脉高压症并发症和肝衰竭,并且他们的预后较差166。尽管皮质类固醇和N-乙酰半胱氨酸等药物疗法在短期内对酒精性肝病有所帮助,但肝移植仍是唯一的治疗选择166。

酒精性肝病的肝移植代表着伦理、医学和社会心理问题的独特融合,因此,直到最近才开始实施。

来自欧洲的一项颠覆性的小型研究表明,在接受酒精性肝病评估的患者中,有 2%的患者移植后生存率令人满意,明显优于历史对照167。这一结果在美国的一项多中心研究中得到了重复168。

由于捐献的肝脏是一种宝贵的资源,因此这一话题总能引发激烈的争论,为此多个移植中心制定了政策,以满足肝脏移植的医学要求并在伦理上具有优先权的患者为重点,同时减少未戒酒 6 个月的患者酒精依赖复发的可能性。

非酒精性脂肪肝

随着肥胖人群的不断扩大,到 2030 年,美国大约一半的成年人将会肥胖169。肥胖与非酒精性脂肪肝(NAFLD)直接相关,NAFLD 现已成为世界上慢性肝病最常见的病因,影响着 30%的成年人170。

据估计,到 2030 年,美国将有 10 亿人患有 NAFLD,其中 2500 万人患有非酒精性脂肪性肝炎(NASH),250 万人患有肝硬化、肝细胞癌和需要肝移植171。

NASH 和肝纤维化患者的肝脏相关和全因死亡率增加,心血管疾病是 NAFLD 患者最常见的死因172。

随着 NASH 患者持续的慢性肝损害,人们也认识到,即使没有肝硬化,NASH 患者出现肝细胞癌的比率也会增加173。事实上,NASH 已成为美国肝移植发展最快的适应症,并已取代丙型肝炎导致的肝硬化174。

研究表明,减轻 7%~10%的体重,可以改善 NASH,包括肝纤维化;然而,这对患者来说,通常都很难坚持。目前还没有 FDA 批准的、可用于 NASH 的治疗方法,尽管美国肝病学会的最新指南建议,对活检证实为 NASH 的患者使用维生素 E 和吡格列酮175。

在过去的十年里,我们对 NAFLD 病理生理学的理解有了长足的进步,这推动了医疗人员寻找新的药物选择。由于 NAFLD 的发病机制错综复杂,有多个靶点可供选择,我们很可能需要同时针对多个靶点来阻止肝病的进展。

尽管有一系列的药物正在进行临床前和早期临床研究,但只有三个药物(奥贝胆酸、Elafibranor 和 Cenicriviroc)处于 3 期临床试验后期阶段176。在最近的一项中期分析中,与安慰剂相比,在 NASH 和 2~3 期纤维化患者中,奥贝胆酸改善了肝纤维化177。

在未来 5 年内,NASH 和纤维化的治疗方法,有望被批准。

但是显然,仅靠药物治疗并不是解决问题的办法。我们需要继续进行预防性努力,以遏制肥胖症的流行并减少其代谢并发症。我们还需要开发可靠的、可获得的、无创的工具,来诊断 NAFLD 患者并对其进行风险分层。

在过去十年中,临床胰脏学的两个主要发展是:对自身免疫性胰腺炎(AIP)的诊断和治疗有所进步,以及胰周液体积聚(PFCs)微创技术的迅速发展,特别是在胰腺包裹性坏死的情况下。

自身免疫性胰腺炎

最近的研究阐明了 I 型 AIP 的免疫学基础,并提出了潜在的治疗靶点。体液免疫是一个关键因素,基于病人对 B 细胞耗竭疗法的应答。

然而,近期的研究表明,T 细胞与体液免疫的作用相当,甚至 T 细胞的作用更大,比如 TH1/TH2 失衡178、调节性 T 细胞异常表达179和淋巴毒素表达增加180可以证明这一点。进一步的实验证据表明,T 细胞定向疗法(如环孢素)可能可以起到作用181。

临床上,AIP 的分类已进一步细化。2 型 AIP(特发性导管中心性胰腺炎)现在被认为是一种不同于 I 型 AIP 的疾病过程。比较研究达成了一个共识,强调了着两者之间的差异182,183。与 1 型 AIP 患者相比,2 型 AIP 患者更年轻,其他器官并不受累,血清 IgG4 水平正常。

不幸的是,2 型 AIP 的发病机制仍不清楚,这阻碍了诊断标志物和靶向疗法的发展。

AIP 的诊断标准现在已经有了共识,这些标准统一了临床、血清学和病理学特征。对于缺乏血清 IgG4 水平升高或典型影像学表现的病人,有时需要胰腺活检。一项对 110 例疑似 1 型 AIP 患者的随机试验表明,EUS 引导下的核心活检针优于标准细胞学针,其中 78%的 AIP 患者都能提供足够组织以供核心活检针检测。

由于其罕见性,AIP 的治疗主要基于小型观察研究和临床经验。近年来,医疗人员提出了一些有效的治疗方法184-186。皮质类固醇仍然是诱导缓解 AIP 的主要药物。而利妥昔在类固醇难治性 AIP 和类固醇不耐受患者中也取得了成功187。

预防复发的维持治疗策略,还有待进一步研究。一项随机试验显示,与停止使用类固醇的患者相比,维持性皮质类固醇治疗的患者复发率明显降低188。

胰周液体积聚的治疗

2013 年修订的亚特兰大急性胰腺炎分类,根据病因、持续时间、固体碎片的存在和囊壁的发展,将 PFCs 分类为 4 种不同的类别189。这种更精确的定义使临床医生能够更准确地诊断、治疗和预测每种类型 PFC 的转归,包括急性胰周液体积聚、急性坏死物积聚、胰腺假性囊肿和包裹性坏死。

治疗急性胰周液体积聚和急性坏死物积聚的首要原则,是延迟干预,以允许溶解或包裹积聚物。急性胰周液体积聚有时会发展成假性囊肿,通常会自行消退。急性坏死物积聚通常会发展成包裹性坏死,而这个情况的解决难度更大。

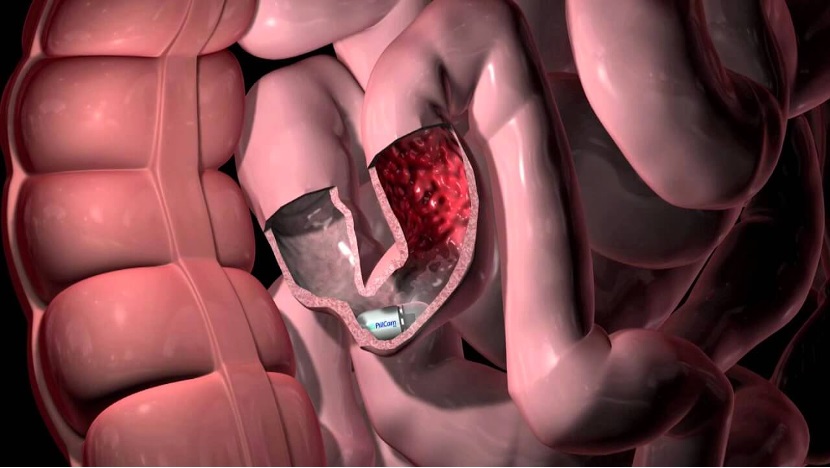

近十年来,微创内窥镜技术不断改进,可以进行引流或直接清除假性囊肿和包裹性坏死,该技术的主要进展是使用腔内贴壁金属支架,以方便进行胰腺切开术190。一项多中心试验表明,在治疗坏死和假性囊肿方面,微创手术比外科手术更佳191。

在过去的十年里,流行病学数据表明,IBD 正逐渐转变为全球性疾病192,193。亚洲、非洲和拉丁美洲的新兴工业化国家报告称,IBD 的发病率迅速上升,这与20世纪后半叶西方国家的 IBD 发病率相似192,194,195。相比之下,在北美、欧洲和大洋洲,IBD 的发病率已开始稳定,在某些地区,发病率有所下降192。

然而,西方国家正处于患病率恶化期,IBD 患者总数稳步攀升193,196。来自加拿大和苏格兰的流行数据表明,IBD 的流行率在 2020 年为 0.7%,预计到 2030 年将攀升至 1%196-198。

此外,IBD 的人口正在老龄化。在接下来的十年里,消化内科诊所将需要与老年人群的 IBD 及共病相斗争198,199。

IBD 的全球负担将使全球的医疗保健系统面临压力,这就需要在提供医疗保健和个性化的 IBD 监测和管理方法方面进行创新200。

在过去的十年中,最重要的变化之一是不再使用主要的临床症状来评估治疗反应,而是转向粘膜愈合的终点。

临床试验转归指标已调整为:患者报告结局和包括粪便钙卫蛋白、血清炎症标志物和内窥镜检查在内的客观评估作为共同终点201。

这种策略已经证明了其有效性,因为克罗恩病的严格控制管理(CALM)试验表明,使用生物标志物(C-反应蛋白或钙卫蛋白)进行的早期优化治疗,其临床效果、黏膜愈合和成本效益优于单独的临床评估202。

然而,即使基于风险分层的早期优化治疗,许多患者仍然对治疗无应答或应答不佳。IBD 的生物标志物、遗传学和精准医学等新兴领域的蓬勃发展,使得在现有通用评估之外的因素基础上制定个性化策略成为可能,以提高早期和持续缓解的可能性203。

在过去的十年里,我们对 IBD 患者炎症级联反应背后复杂的病理生理通路有了更好的理解。

目前被批准用于 IBD 的生物制剂有:肿瘤坏死因子小分子抑制剂(英夫利昔单抗、阿达木单抗、戈利木单抗和聚乙二醇结合赛妥珠单抗)、整合素(维多珠单抗)、白细胞介素-12/23(尤特克单抗)和JAK激酶(托法替尼)。

这些药物对中度至重度活动性 IBD 的患者有效204,205。然而,这些药物仅能治愈 IBD 患者少于一半的黏膜206。

考虑到现有的未被满足的需求,许多新的疗法正在成为未来治疗 IBD 患者的目标。各种有前景的机制已经被确定,并正在临床试验的不同阶段进行评估。一些具有新机制的药物包括:

● 阻断下游信号通路,如 JAK 激酶抑制剂,包括非戈替尼 [JAK 1]、乌帕替尼 [JAK 1]、巴瑞替尼 [JAK 1,2]、TD-1473[JAK 1,2,3]、peficitinib[JAK 1,2,3]、PF-06651600[JAK 3 和 TEC 激酶]、伊他替尼 [JAK 1]、PF-06700841[JAK 1 和 Tyk-2] 和 BMS-986165[Tyk-2];

● 阻断促炎性细胞因子,如抗白细胞介素-23 制剂,包括 brazikumab(MEDI2070)、risankizumab(BI 655066)、古塞库单抗(Tremfya)、mirikizumab(LY3074828)和 tildrakizumab(MK-3222);

● 抗黏附分子,如白细胞迁移抑制剂,包括 etrolizumab,抗黏膜血管粘膜定位蛋白细胞粘附分子 ontamalimab(SHP 647,PF00547659)、abrilumab 和 AJM 300,以及 spingosine-1-磷酸盐调节剂,包括 ozanimod 和 etrasimod207。

针对 IBD 特异性通路的新型生物制剂的出现,为 IBD 患者提供了多种新的治疗方法和更加个性化的治疗机会。对上述药物和其他新型药物的仔细评估和测试,将扩大我们的医疗手段,从而使我们能够为 IBD 患者提供进一步的治疗选择。

参考文献:

1.Binmoeller KF. Shah J A novel lumen-apposing stent for transluminal drainage of nonadherent extraintestinal fluid collections. Endoscopy 2011;43:337–42.

2. US Food and Drug Administration. De novo classification request for Xlumena axios stent and delivery system. (https://www.accessdata.fda. gov/cdrh_docs/reviews/K123250.pdf). Accessed June 17, 2020.

3. US Department of Health & Human Services. (https://www.accessdata. fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf16/K163272.pdf). Accessed February 28, 2020.

4. Itoi T, Binmoeller KF, Shah J, et al. Clinical evaluation of a novel lumenapposing metal stent for endosonography-guided pancreatic pseudocyst and gallbladder drainage (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc 2012;75: 870–6.

5. Itoi T, Binmoeller KF. EUS-guided choledochoduodenostomy using a biflanged lumen-apposing metal stent (with video). Gastrointest Endosc 2014;79:715.

6. Barthet M, Binmoeller KF, Vanbiervliet G, et al. Natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery gastroenterostomy with a biflanged lumen-apposing stent: First clinical experience (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc 2015;81:215–8.

7. Kedia P, Kumta N, Sharaiha R, et al. Bypassing the bypass: Endoscopic ultrasound-directed transgastric ERCP (EDGE) for Roux-en-Y anatomy. Gastrointest Endosc 2014;81:223–4.

8. Sumiyama K, Gostout CJ, Rajan E, et al. Submucosal endoscopy with mucosal flap safety valve. Gastrointest Endosc 2007;65:688–94.

9. Pasricha PJ, Hawari R, Ahmed I, et al. Submucosal endoscopic esophageal myotomy: A novel experimental approach for the treatment of achalasia. Endoscopy 2007;39:761–4.

10. Inoue H, Minami H, Kobayashi Y, et al. Peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) for esophageal achalasia. Endoscopy 2010;42:265–71.

11. Xu MD, Cai MY, Zhou PH, et al. Submucosal tunneling endoscopic resection: A new technique for treating upper GI submucosal tumors originating from the muscularis propria layer (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc 2012;75:195–9.

12. Khashab MA, Stein E, Clarke JO, et al. Gastric peroral endoscopic myotomy for refractory gastroparesis: First human endoscopic pyloromyotomy (with video). Gastrointest Endosc 2013;78:764–8.

13. Li QL, Chen WF, Zhang XC, et al. Submucosal tunneling endoscopic septum division: A novel technique for treating Zenker’s diverticulum. Gastroenterology 2016;151:1071–4.

14. Inoue H, Sato H, Ikeda H, et al. Peroral endoscopic myotomy:A series of 500 patients. J Am Coll Surg 2015;221:256–64.

15. Teitelbaum EN, Dunst CM, Reavis KM, et al. Clinical outcomes five years after POEM for treatment of primary esophageal motility disorders. Surg Endosc 2018;32:421–7.

16. Li QL, Wu QN, Zhang XC, et al. Outcomes of peroral endoscopic myotomy for treatment of esophageal achalasia with amedian followup of 49 months. Gastrointest Endosc 2018;87:1405–12.

17. Dacha S, Wang L, Xiaoyu L, et al. Outcomes and quality of life assessment after per oral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) performed in the endoscopy unit with trainees. Surg Endosc 2018;32:3046–54.

18. Chen T, Zhang C, Yao LQ, et al. Management of the complications of submucosal tunneling endoscopic resection for upper gastrointestinal submucosal tumors. Endoscopy 2016;48:149–55.

19. Ye LP, Zhang Y, Mao XL, et al. Submucosal tunneling endoscopic resection for small upper gastrointestinal subepithelial tumors originating from the muscularis propria layer. Surg Endosc 2014;28: 524–30.

20. Chen HM, Li BW, Li LY, et al. Current status of endoscopic resection of gastric subepithelial tumors. Amer J Gastroenterol 2019;114:718–25.

21. Khashab MA, Ngamruengphong S, Carr-Locke D, et al. Gastric peroral endoscopic myotomy for refractory gastroparesis: Results from the first multicenter study on endoscopic pyloromyotomy (with video). Gastrointest Endosc 2017;85:123–8.

22. Gonzalez JM, Lestelle V, Benezech A, et al. Gastric peroral endoscopic myotomy with antropyloromyotomy in the treatment of refractory gastroparesis: Clinical experience with follow-up and scintigraphic evaluation (with video). Gastrointest Endosc 2017;85:132–9.

23. Dacha S, Mekaroonkamol P, Li L, et al. Outcomes and quality-of-life assessment after gastric peroral endoscopic pyloromyotomy (with video). Gastrointest Endosc 2017;86:282–9.

24. Albers DV, Kondo A, Bernardo WM, et al. Endoscopic versus surgical approach in the treatment of Zenker’s diverticulum: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Endosc Int Open 2016;4:E678–86.

25. Ishaq S, Hassan C, Antonello A, et al. Flexible endoscopic treatment for Zenker’s diverticulum: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc 2016;83:1076–89.

26. Hirao M, Masuda K, Asanuma T, et al. Endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer and other tumors with local injection of hypertonic salineepinephrine. Gastrointest Endosc 1988;34:264–9.

27. Chen H, Li B, Li L, et al. Current status of endoscopic resection of gastric subepithelial tumors. Am J Gastroenterol 2019;114:718–25.

28. Verfaillie CJ, Bruno MJ, Voor in ’t Holt AF, et al. Withdrawal of a noveldesign duodenoscope ends outbreak of a VIM-2-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa [published correction appears in Endoscopy. 2015 Jun;47(6):502]. Endoscopy 2015;47:493–502.

29. Epstein L, Hunter JC, Arwady MA, et al. New Delhi metallob- lactamase-producing carbapenem-resistant Escherichia coli associated with exposure to duodenoscopes. JAMA 2014;312:1447–55.

30. Humphries RM, Yang S, Kim S, et al. Duodenoscope-related outbreak of a carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae identified using advanced molecular diagnostics. Clin Infect Dis 2017;65:1159–66.

31. Rubin ZA, Kim S, Thaker AM, et al. Safely reprocessing duodenoscopes: Current evidence and future directions. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;3:499–508.

32. (http://wayback.archive-it.org/7993/20170722150658/https://www.fda. gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/ucm454766.htm). Accessed February 28, 2020.

33. Snyder GM, Wright SB, Smithey A, et al. Randomized comparison of 3 high-level disinfection and sterilization procedures for duodenoscopes. Gastroenterology 2017;153:1018–25.

34. Bartles RL, Leggett JE, Hove S, et al. A randomized trial of single versus double high-level disinfection of duodenoscopes and linear echoendoscopes using standard automated reprocessing. Gastrointest Endosc 2018;88:306–13.e2.

35. (https://www.fda.gov/media/132346/download). Accessed February 28, 2020.

36. (https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/safety-communications/fdarecommending- transition-duodenoscopes-innovative-designsenhance- safety-fda-safety-communication). Accessed February 28, 2020.

37. Ross AS, Bruno MJ, Kozarek RA, et al. Novel single-use duodenoscope compared with 3 models of reusable duodenoscopes for ERCP: A randomized bench-model comparison. Gastrointest Endosc 2020;91: 396–403.

38. Muthusamy VR, Bruno MJ, Kozarek RA, et al. Clinical evaluation of a single-use duodenoscope for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography [published online ahead of print, 2019 Nov 6]. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;S1542–3565(19):31261–3.

39. Lee JK, Merchant SA, Schneider JL, et al. Proton pump inhibitor use and risk of gastric, colorectal, liver, and pancreatic cancers in a communitybased population. Am J Gastroenterol 2020;115:706–15.

40. Kurlander JE, Kennedy JK, Rubenstein JH, et al. Patients’ perceptions of proton pump inhibitor risks and attempts at discontinuation:A national Survey. Am J Gastroenterol 2019;114:244–9.

41. Freedberg DE, Kim LS, Yang YX. The risks and benefits of long-term use of proton pump inhibitors: Expert review and best practice advice from the American Gastroenterological Association. Gastroenterology 2017; 152:706–15.

42. Moayyedi P, Eikelboom JW, Bosch J, et al. Safety of proton pump inhibitors based on a large, multi-year, randomized trial of patients receiving rivaroxaban or aspirin. Gastroenterology 2019;157:682–91.e2.

43. Kinoshita Y, Ishimura N, Ishihara S. Management of GERD: Are potassium-competitive acid blockers superior to proton pump inhibitors? Am J Gastroenterol 2018;113:1417–9.

44. Patel A, Sayuk GS, Gyawali CP. Parameters on esophageal pHimpedance monitoring that predict outcomes of patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13: 884–91.

45. Gyawali CP, Kahrilas PJ, Savarino E, et al. Modern diagnosis of GERD: The Lyon consensus. Gut 2018;67:1351–62.

46. Frazzoni M, de BortoliN, Frazzoni L, et al. The added diagnostic value of postreflux swallow-induced peristaltic wave index and nocturnal baseline impedance in refractory reflux disease studied with ontherapy impedance-pH monitoring. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2017;29; (doi:10.1111/nmo.12947).

47. Frazzoni M, Savarino E, de Bortoli N, et al. Analyses of the post-reflux swallow-induced peristaltic wave index and nocturnal baseline impedance parameters increase the diagnostic yield of impedance-pH monitoring of patients with reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;14:40–6.

48. Martinucci I, de Bortoli N, Savarino E, et al. Esophageal baseline impedance levels in patients with pathophysiological characteristics of functional heartburn. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2014;26:546–55.

49. Ates F, Yuksel ES, Higginbotham T, et al. Mucosal impedance discriminates GERD from non-GERD conditions. Gastroenterology 2015;148:334–43.

50. Patel DA, Higginbotham T, Slaughter JC, et al. Development and validation of a mucosal impedance contour analysis systemto distinguish esophageal disorders. Gastroenterology 2019;156:1617–26.e1.

51. Spechler SJ, Hunter JG, Jones KM, et al. Randomized trial of medical versus surgical treatment for refractory heartburn. N Engl J Med 2019; 381:1513–23.

52. Patel A, Sayuk GS, Gyawali CP. Acid-based parameters on pHimpedance testing predict symptom improvement with medical management better than impedance parameters. Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109:836–44.

53. Patel A, Sayuk GS, Kushnir VM, et al. GERD phenotypes from pHimpedance monitoring predict symptomatic outcomes on prospective evaluation. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2016;28:513–21.

54. Bell R, Lipham J, Louie B, et al. Laparoscopic magnetic sphincter augmentation versus double-dose proton pump inhibitors for management of moderate-to-severe regurgitation in GERD: A randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc 2019;89:14–22.e1.

55. Bell R, Lipham J, Louie BE, et al. Magnetic sphincter augmentation superior to proton pump inhibitors for regurgitation in a 1-year randomized trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;10:S1542–3565; (doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.08.056).

56. Hunter JG, Kahrilas PJ, Bell RC, et al. Efficacy of transoral fundoplication vs omeprazole for treatment of regurgitation in a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology 2015;148:324–33.e5.

57. Shaheen NJ, Falk GW, Iyer PG, et al. American College of Gastroenterology clinical guideline: Diagnosis and management of Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol 2016;111:30–50.

58. Jankowski JAZ, de Caestecker J, Love SB, et al. Esomeprazole and aspirin in Barrett’s oesophagus (AspECT): A randomised factorial trial. The Lancet 2018;392:400–8.

59. Chen MJ, Chen CC, Chen YN, et al. Systematic review with metaanalysis: Concomitant therapy vs. triple therapy for the first-line treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol 2018; 113:1444–14576.

60. Sonnenberg A, Turner KO, Genta RM. Low prevalence of Helicobacter pylori-positive peptic ulcers in private outpatient endoscopy centers in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol 2020;115:244–50.

61. Tan MC, Mallepally N, Liu Y, et al. Demographic and lifestyle risk factors for gastric intestinal metaplasia among US Veterans. Am J Gastroenterol 2020;115:381–7.

62. Kaji K, Hashiba A, Uotani C, et al. Grading of atrophic gastritis is useful for risk stratification in endoscopic screening for gastric cancer. Am J Gastroenterol 2019;114:71–9.

63. Talley NJ, Walker MM. The rise and rise of eosinophilic gut diseases including eosinophilic esophagitis is probably not explained by the disappearance of Helicobacter pylori, so who or what’s to blame? Am J Gastroenterol 2018;113:941–4.

64. Dellon ES, Speck O, Woodward K, et al. Clinical and endoscopic characteristics do not reliably differentiate PPI-responsive esophageal eosinophilia and eosinophilic esophagitis in patients undergoing upper endoscopy: A prospective cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108: 1854–60.

65. Moawad FJ, Veerappan GR, Dias JA, et al. Randomized controlled trial comparing aerosolized swallowed fluticasone to esomeprazole for esophageal eosinophilia. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108:366–72.

66. Molina-Infante J, Lucendo AJ. Proton pump inhibitor therapy for eosinophilic esophagitis: A paradigm shift. Am J Gastroenterol 2017; 112:1770–3.

67. Lucendo AJ, Molina-Infante J, Arias A, et al. Guidelines on eosinophilic esophagitis: Evidence-based statements and recommendations for diagnosis and management in children and adults. United Eur Gastroenterol J 2017;5:335–58.

68. Straumann A, Hoesli S, Bussmann C, et al. Anti-eosinophil activity and clinical efficacy of the CRTH2 antagonist OC000459 in eosinophilic esophagitis. Allergy 2013;68:375–85.

69. Dellon ES, Katzka DA, Collins MH, et al. Budesonide oral suspension improves symptomatic, endoscopic, and histologic parameters compared with placebo in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2017;152:776–86.e5.

70. Hirano I, CollinsMH,Assouline-Dayan Y, et al. RPC4046, a monoclonal antibody against IL13, reduces histologic and endoscopic activity in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2019;156: 592–603.e10.

71. Lucendo AJ, Miehlke S, Schlag C, et al. Efficacy of budesonide orodispersible tablets as induction therapy for eosinophilic esophagitis in a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology 2019;157: 74–86.e15.

72. Miehlke S, Hruz P, Vieth M, et al. A randomised, double-blind trial comparing budesonide formulations and dosages for short-term treatment of eosinophilic oesophagitis. Gut 2016;65:390–9. 73. Kahrilas PJ, Bredenoord AJ, Fox M, et al. The Chicago Classification of esophageal motility disorders, v3.0. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2015;27: 160–74.

74. Penagini R, Gyawali CP. Evaluation of esophageal contraction reserve using HRM in symptomatic esophageal disease. J Clin Gastroenterol 2019;53:322–30.

75. Ponds FA, Fockens P, Lei A, et al. Effect of peroral endoscopic myotomy vs pneumatic dilation on symptom severity and treatment outcomes among treatment-naive patients with achalasia: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2019;322:134–44.

76. Rex DK, Schoenfeld PS, Cohen J, et al. Quality indicators for colonoscopy. Gastroenterol Endosc 2015;81:31–53.

77. Jang JY, Chun HJ. Bowel preparations as quality indicators for colonoscopy. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:2746–50.

78. Menees SB, Kim HM, Wren P, et al. Patient compliance and suboptimal bowel preparation with split-dose bowel regimen in average-risk screening colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 2014;79:811–20.

79. Nguyen DL, Wieland M. Risk factors predictive of poor quality preparation during average risk colonoscopy screening: The importance of health literacy. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis 2010;19:369–72.

80. Johnson DA, Barkun AN, Cohen LB, et al. Optimizing adequacy of bowel cleansing for colonoscopy: Recommendations from the US Multi- Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology 2014;147: 903–24.

81. Bucci C, Rotondano G, Hassan C, et al. Optimal bowel cleansing for colonoscopy: Split the dose! A series of meta-analyses of controlled studies. Gastrointest Endosc 2014;80:566–76.e562.

82. Kilgore TW, Abdinoor AA, Szary NM, et al. Bowel preparation with split-dose polyethylene glycol before colonoscopy: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Gastrointest Endosc 2011;73:1240–5.

83. Avalos DJ, Castro FJ, Zuckerman MJ, et al. Bowel preparations administered the morning of colonoscopy provide similar efficacy to a split-dose regimen: A meta analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol 2017;52: 859–68.

84. Lebwohl B, Wang TC, Neugut AI. Socioeconomic and other predictors of colonoscopy preparation quality. Dig Dis Sci 2010;55:2014–20.

85. Siddiqui AA, Yang K, Spechler SJ, et al. Duration of the interval between the completion of bowel preparation and the start of colonoscopy predicts bowel-preparation quality. Gastrointest Endosc 2009;69:700–6.

86. Kanth P, Grimmett J, Champine M, et al. Hereditary colorectal polyposis and cancer syndromes: A primer on diagnosis and management. Am J Gastroenterol 2017;112:1509–25.

87. Samadder NJ, Curtin K, Tuohy TM, et al. Increased risk of colorectal neoplasia among family members of patients with colorectal cancer: A population-based study in Utah. Gastroenterology 2014;147:814–21.

88. Samadder NJ, Smith KR, Hanson H, et al. Increased risk of colorectal cancer among family members of all ages, regardless of age of index case at diagnosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13:2305–11.

89. Leddin D, Lieberman DA, Tse F, et al. Clinical practice guideline on screening for colorectal cancer in individuals with a family history of nonhereditary colorectal cancer or adenoma: The Canadian Association of Gastroenterology Banff Consensus. Gastroenterology 2018;155: 1325–47.

90. Yurgelun MB, Kulke MH, Fuchs CS, et al. Cancer susceptibility gene mutations in individuals with colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2017;35: 1086–95.

91. Valle L, Vilar E, Tavtigian SV, et al. Genetic predisposition to colorectal cancer: Syndromes, genes, classification of genetic variants and implications for precision medicine. J Pathol 2019;247:574–88.

92. AlDubayan SH, Giannakis M, Moore ND, et al. Inherited DNA-repair defects in colorectal cancer. Am J Hum Genet 2018;102:401–14.

93. Ribas A, Wolchok JD. Cancer immunotherapy using checkpoint blockade. Science 2018;359:1350–5.

94. Ellis L, Shale MJ, Coleman MP. Carcinoid tumors of the gastrointestinal tract: Trends in incidence in England since 1971. Am J Gastroenterol 2010;105:2563–9.

95. Ducreux M, Ruszniewski P, Chayvialle JA, et al. The antitumoral effect of the long-acting somatostatin analog lanreotide in neuroendocrine tumors. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:3276–81.

96. Dillon JS, Kulke MH,H¨orsch D, et al. Time to sustained improvement in bowel movement frequency with telotristat ethyl: Analyses of phase III studies in carcinoid syndrome. J Gastrointest Cancer 2020 (doi:10.1007/ s12029-020-00375-2).

97. Hope TA, Abbott A, Colucci K, et al. NANETS/SNMMI procedure standard for somatostatin receptor-based peptide receptor radionuclide therapy with DOTATATE. J Nucl Med 2019;60:937–43.

98. MoonCM,Huh KC, Jung SA, et al. Long-term clinical outcomes of rectal neuroendocrine tumors according to the pathologic status after initial endoscopic resection: A kasid multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol 2016;111:1276–85.

99. Rex DK, Schoenfeld PS, Cohen J, et al. Quality indicators for colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol 2015;110:72–90.

100. Lund M, Trads M, Njor SH, et al. Quality indicators for screening colonoscopy and colonoscopist performance and the subsequent risk of interval colorectal cancer: A systematic review. JBI Database Syst Rev Implement Rep 2019;17:2265–300.

101. ASGE Technology Committee; Trindade AJ, Lichtenstein DR, Aslanian HR, et al. Devices and methods to improve colonoscopy completion (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc 2018;87:625–34.

102. Murray JA, Van Dyke C, Plevak MF, et al. Trends in the identification and clinical features of celiac disease in a North American Community, 1950–2001. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2003;1:19–27. 103. Choung RS, Unalp-AridaA, Ruhl CE, et al. Less hidden celiac disease but increased gluten avoidance without a diagnosis in the United States: Findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys from 2009 to 2014. Mayo Clin Proc;S0025-6196(16)30634-6 (doi:10. 1016/j.mayocp.2016.10.012).

104. Rubio-Tapia A, Ludvigsson JF, Brantner TL, et al. The prevalence of celiac disease in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107: 1538–44.

105. Vriezinga SL, Auricchio R, Bravi E, et al. Randomized feeding intervention in infants at high risk for celiac disease. N Engl J Med 2014; 371(14):1304–15.

106. Lionetti E, Castellaneta S, Francavilla R, et al. Introduction of gluten, HLA status, and the risk of celiac disease in children.NEngl J Med 2014; 371:1295–303.

107. Ludvigsson JF, Lebwohl B. Three papers indicate that amount of gluten play a role for celiac disease—But only a minor role. Acta Paediatr 2020; 109:8–10.

108. Shah S, Akbari M, Vanga R, et al. Patient perception of treatment burden is high in celiac disease compared with other common conditions. Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109:1304–11.

109. Lerner BA, Phan Vo LT, Yates S, et al. Detection of gluten in gluten-free labeled restaurant food: Analysis of crowd-sourced data. Am J Gastroenterol 2019;114:792–7.

110. Mukewar SS, Sharma A, Rubio-Tapia A, et al. Open-capsule budesonide for refractory celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2017;112:959–67.

111. Leffler DA, Kelly CP, Green PHR, et al. Larazotide acetate for persistent symptoms of celiac disease despite a gluten-free diet: A randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology 2015;148:1311–9.

112. Murray JA, Kelly CP, Green PHR, et al. No difference between latiglutenase and placebo in reducing villous atrophy or improving symptoms in patients with symptomatic celiac disease. Gastroenterology 2017;152:787–98.

113. Truitt KE, Daveson AJM, Ee HC, et al. Randomised clinical trial: A placebo-controlled study of subcutaneous or intradermalNEXVAX2, an investigational immunomodulatory peptide therapy for coeliac disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2019;50:547–55.

114. Jeppesen PB, Pertkiewicz M, Messing B, et al. Teduglutide reduces need for parenteral support among patients with short bowel syndrome with intestinal failure. Gastroenterology 2012;143:1473.

115. Seidner DL, Fujioka K, Boullata JI, et al. Reduction of parenteral nutrition and hydration support and safety with long-term teduglutide treatment in patient with short bowel syndrome-associated intestinal failure: STEPS-3 study. Nutr Clin Pract 2018;33:520–7.

116. Kocoshis SA, Merritt RJ, Hill S, et al. Safety and efficacy of teduglutide in pediatric patients with intestinal failure due to short bowel syndrome: A 24-week, phase III study. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2020;44:621–31.

117. Hvistendahl M, Brandt CF, Tribler S, et al. Effect of liraglutide treatment on jejunostomy output in patients with short bowel syndrome: An openlabel pilot study. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2018;42:112–21.

118. Wismann P, Pedersen Sl, Hansen G, et al. Novel GLP-1/GLP-2 coagonists display marked effects on gut volume and improved glycemic control in mice. Physiol Behav 2018;192:72–81.

119. Drossman DA, Tack J, Ford AC, et al. Neuromodulators for functional gastrointestinal disorders (disorders of gut-brain interaction): A rome foundation working team report. Gastroenterology 2018;154:1140–71.

120. Mayer EA, Labus J, Aziz Q, et al. Role of brain imaging in disorders of brain-gut interaction: A rome working team report. Gut 2019;68: 1701–15.

121. Simren M, Tornblom H, Palsson OS, et al. Cumulative effects of psychologic distress, visceral hypersensitivity, and abnormal transit on patient-reported outcomes in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2019;157:391–402.e2.

122. Keefer L, Palsson OS, Pandolfino JE. Best practice update: Incorporating psychogastroenterology into management of digestive disorders. Gastroenterology 2018;154:1249–57.

123. Everitt HA, Landau S, O’Reilly G, et al. Assessing telephone-delivered cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) and web-delivered CBT versus treatment as usual in irritable bowel syndrome (ACTIB): A multicentre randomized trial. Gut 2019;68:1613–23.

124. Bonnert M, Olen O, Lalouni M, et al. Internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy for adolescents with irritable bowel syndrome: A randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2017;112:152–62.

125. Lalouni M, Ljotsson B, Bonnert M, et al. Clinical and cost effectiveness of online cognitive behavioral therapy in children with functional abdominal pain disorders. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;17: 2236–44.e11.

126. Lowen MB, Mayer EA, Sjoberg M, et al. Effect of hypnotherapy and educational intervention on brain response to visceral stimulus in the irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013;37: 1184–97.

127. Flik CE, Laan W, Zuithoff NPA, et al. Efficacy of individual and group hypnotherapy in irritable bowel syndrome (IMAGINE): A multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;4: 20–31.

128. Black CJ, Yuan Y, Selinger CP, et al. Efficacy of soluble fibre, antispasmodic drugs, and gut-brain neuromodulators in irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic network meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;5:117–31.

129. Muller-Lissner SA, Fumagalli I, Bardhan KD, et al. Tegaserod, a 5-HT(4) receptor partial agonist, relieves symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome patients with abdominal pain, bloating and constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2001;15:1655–66.

130. Camilleri M, Kerstens R, Rykx A, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of prucalopride for severe chronic constipation. N Engl J Med 2008;358: 2344–54.

131. Carbone F, Van den Houte K, Clevers E, et al. Prucalopride in gastroparesis: A randomized placebo-controlled crossover study. Am J Gastroenterol 2019;114:1265–74.

132. Chey WD, Lembo AJ, Lavins BJ, et al. Linaclotide for irritable bowel syndrome with constipation: A 26-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to evaluate efficacy and safety. Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:1702–12.

133. Brenner DM, Fogel R, Dorn SD, et al. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of plecanatide in patients with irritable bowel syndrome with constipation: Results of two phase 3 randomized clinical trials. Am J Gastroenterol 2018;113:735–45.

134. Chey WD, Lembo A, Rosenbaum DP. Efficacy of tenapanor in treating patients with irritable bowel syndrome with constipation: A 12-week placebo-controlled phase 3 trial (T3MPO). Am J Gastroenterol 2020; 115:281–93.

135. Lembo AJ, Lacy BE, Zuckerman M, et al. Eluxadoline for irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea. NEJM 2016;374:242–53.

136. Brenner DM, Sayuk GS, Gutman CR, et al. Efficacy and safety of eluxadoline in patients with irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea who report inadequate symptom control with loperamide: RELIEF phase 4 study. Am J Gastroenterol 2019;114:1502–11.

137. Weerts ZZRM, Masclee AAM, Witteman BJM, et al. Efficacy and safety of peppermint oil in a randomized double-blind trial of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2020;158:123–36.

138. Slattery SA, Niaz O, Aziz Q, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: The prevalence of bile acid malabsorption in the irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhoea. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015;42:3–11.

139. Sadowski DC, Camilleri M, Chey WD, et al. Canadian Association of Gastroenterology clinical practice guideline on the management of bile acid diarrhea. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;18:24–41.

140. KlemF,WadhwaA, Prokop LJ, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and outcomes of irritable bowel syndrome after infectious enteritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2017;152:1042–54.e1.

141. Futagami S, Itoh T, Sakamoto C. Systematic review with meta-analysis: Post-infectious functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015;41: 177–88.

142. Shah A, Talley NJ, Jones M, et al. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis of case-control studies. Am J Gastroenterol 2020;115:190–201.

143. Pimentel M, Lembo A, Chey WD, et al. Rifaximin therapy for patients with irritable bowel syndrome without constipation. NEngl J Med 2011; 364:22–32.

144. Tan VP, Liu KS, Lam FY, et al. Randomised clinical trial: Rifaximin versus placebo for the treatment of functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2017;45:767–76.

145. Fodor AA, Pimentel M, Chey WD, et al. Rifaximin is associated with modest, transient decreases in multiple taxa in the gut microbiota of patients with diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Gut Microbes 2019;10:22–33.

146. Ford AC, Harris LA, Lacy BE, et al. Systematic review with metaanalysis: The efficacy of prebiotics, probiotics, synbiotics and antibiotics in irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2018;48:1044–60.

147. Ford AC, Quigley EM, Lacy BE, et al. Efficacy of prebiotics, probiotics, and synbiotics in irritable bowel syndrome and chronic idiopathic constipation: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109:1547–61.

148. Osadchiy V, Martin CR, Mayer EA. The gut-brain axis and the microbiome: Mechanisms and clinical implications. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;17:322–32.

149. Labus JS, Osadchiy V, Hsiao EY, et al. Evidence for an association of gut microbial Clostridia with brain functional connectivity and gastrointestinal sensorimotor function in patients with irritable bowel syndrome, based on tripartite network analysis. Microbiome 2019;7:45.

150. Pinto-Sanchez MI, Hall GB, Ghajar K, et al. Probiotic bifidobacterium longum NCC3001 reduces depression scores and alters brain activity: A pilot study in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2017;153:448–59.

151. Xu D, Chen VL, Steiner CA, et al. Efficacy of fecal microbiota transplantation in irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2019;114:1043–50.

152. El-Salhy M, Hatlebakk JG, Gilja OH, et al. Efficacy of faecal microbiota transplantation for patients with irritable bowel syndrome in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Gut 2020;69: 859–67.

153. Ekekezie C, Perler BK, Wexler A, et al. Understanding the scope of do-ityourself fecal microbiota transplant. Am J Gastroenterol 2020;115: 603–7.

154. Dionne J, Ford AC, Yuan Y, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis evaluating the efficacy of a gluten-free diet and a low FODMAPs diet in treating symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 2018;113:1290–300.

155. Hinrichsen H, Benhamou Y, Wedemeyer H, et al. Short-term antiviral efficacy of BILIN 2-61, a hepatitis C virus serine protease inhibitor, in hepatitis C genotype 1 patients. Gastroenterology 2004;127:1347–55.

156. Kwo PY, Lawitz EJ, McCone J, et al. Efficacy of boceprevir, an NS3 protease inhibitor, in combination with peginterferon alfa-2b and ribavirin in treatment -na¨ıve patients with genotype 1 hepatits C infection (SPRINT-1): An open label randomized, multicenter phase 2 trial. Lancet 2010;376:705–16.

157. McHutchison JG, Everson GT, Gordon SC, et al. Telaprevir with peginterferon and ribavirin for chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med 2009;360:1827–38.

158. Lawitz E, Mangia A, Wyles D, et al. Sofobuvir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C infection. N Engl J Med 2014;368:1878–87.

159. Lawitz E, Sulkowski MS, Ghalib R, et al. Simeprevir plus sofosbuvir, with or without ribavirin, to treat chronic infection with hepatitis C virus genotype 1 in non-responders to pegylated interferon and ribavirin and treatment-na¨ıve patients: The COSMOS Randomised study. Lancet 2014;384:1756–65.

160. Feld JJ, Jacobson IM, Hezode C, et al. Sofosbuvir and velpatasvir for HCV genotype 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6 infection. N Engl J Med 2015;373: 2599–607.

161. Foster GR, Afdhal N, Roberts SK. Sofosbuvir and velpatasivr for HCV genotype 2 and 3 infection. N Engl J Med 2015;373:2608–17.

162. Asselah T, Hezode C, Zadeikis N, et al. ENDURANCE-4: Efficacy and safety of glecaprevir/pibrentasvir (formerly ABT-493/ABT-530) treatment in patients with chronic HCV genotype 4, 5, or 6 infection. Hepatology 2016;64(Suppl 1):114.

163. Zeuzem S, Foster GR, Wang S, et al. Glecaprevir-pibrentasvir for 8 or 12 weeks inHCVgenotype 1 or 3 infection.NEngl J Med 2018;378:354–69.

164. Backus LI, Belperio PS, Shahoumian TA, et al. Direct-acting antiviral sustained virologic response: Impact on mortality in patients without advanced liver disease. Hepatology 2018;68:827–38.

165. Tapper EB, Parikh ND. Mortality due to cirrhosis and liver cancer in the United States, 1999-2016: Observational study. BMJ 2018;362:k2817.

166. Singhal AK, Louvet A, Shah VH, et al. Grand rounds: Alcoholic hepatitis. J Hepatol 2018;69:534–43.

167. Mathurin P, Moreno C, Samuel D, et al. Early liver transplantation for severe alcoholic hepatitis. N Engl J Med 2011;365:1790–800.

168. Lee BP, Mehta N, Platt L, et al. Outcomes of early liver transplantation for patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis. Gastroenterology 2018;155: 422–30.

169. Ward ZJ, Bleich SN, Cradock AL, et al. Projected U.S. State-level prevalence of adult obesity and severe obesity. N Engl J Med 2019;381: 2440–50.

170. Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, et al. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology 2016;64:73–84.

171. Estes C, Razavi H, Loomba R, et al. Modeling the epidemic of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease demonstrates an exponential increase in burden of disease. Hepatology 2018;67:123–33.

172. Dulai PS, Singh S, Patel J, et al. Increased risk of mortality by fibrosis stage in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Systematic review and metaanalysis. Hepatology 2017;65:1557–65.

173. Younossi ZM, Otgonsuren M, Henry L, et al. Association of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in the United States from 2004 to 2009. Hepatology 2015;62: 1723–30.

174. Kwong A, Kim WR, Lake JR, et al. OPTN/SRTR 2018 annual data report: Liver. Am J Transpl 2020;20(Suppl s1):193–299.

175. Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, et al. The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology 2018;67:328–57.

176. Friedman SL, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Rinella M, et al. Mechanisms of NAFLD development and therapeutic strategies. Nat Med 2018;24: 908–22.

177. Younossi ZM, Ratziu V, Loomba R, et al. Obeticholic acid for the treatment of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: Interim analysis from a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2019;394:2184–96.

178. Muller T, Beutler C, Pico AH, et al. Increased T help 2 cytokines in bile from patients with IgG4 related cholangitis disrupt the tight junction associated biliary epithelial cell barrier. Gastroenterology 2013;144: 1116–28.

179. Zen Y, Fujii T, Harada K, et al. Th2 and regulatory immune reactions are increased in immunoglobin G4 related sclerosing pancreatitis and cholangitis. Hepatology 2007;45:1538–46.

180. Sleznik GM, Reding T, Romrig F, et al. Lymphotoxin beta receptor signaling promotes development of autoimmune pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 2012;143:1361–74.

181. Schwaiger T, van den Brandt C, Fitzner B, et al. Autoimmune pancreatitis in MRL/Mp mice is a T cell-mediated disease responsive to cyclosporine A and rapamycin treatment. Gut 2014;63:494–505. 182. Sah RP, Chari ST, Pannala R, et al. Differences in clinical profile and relapse rate of type 1 versus type 2 autoimmune pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 2010;139:140–8.

183. Chari ST, Kloppen G, Zhang L, et al. Histologic and clinical subtypes of autoimmune pancreatitis: The Honolulu Consensus Document. Pancreas 2010;39:549–54.

184. Shimosegawa T, Chari ST, Frulloni L, et al. International consensus diagnostic criteria for autoimmune pancreatitis: Guidelines of the International Association of Pancreatology. Pancreas 2011;40:352–8.

185. Kurita A, Yasukawa S, Zen Y, et al. Comparison of a 22-gauge franseentip needle with a 20-gauge forward-bevel for the diagnosis of type 1 autoimmune pancreatitis: A prospective, randomized, controlled, multicenter study (COMPAS study). Gastrointest Endosc 2020;91: 373–81.

186. Kazaki K, Chari ST, Frulloni, et al. International consensus for treatment of autoimmune pancreatitis. Pancreatology 2017;17:1–6.

187. Hart PA, Topazian MD, Witzig TE, et al. Treatment of refractory autoimmune pancreatitis with immunomodulators and Rituximab. The Mayo Clinic experience. Gut 2013;62:1607–15.

188. Masamune A, Nishimori I, Kikuta K, et al. Randomized controlled trial of long-term maintenance corticosteroid therapy in patients with autoimmune pancreatitis. Gut 2017;66:489–92.

189. Banks BA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, et al. Classification of acute pancreatitis—2012: Revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut 2013;62:102–11.

190. Siddiqui AA, Adler DG, Nieto J, et al. EUS-guided drainage of peripancreatic fluid collections and necrosis by using a novel lumenapposing stent: A large retrospective, multicenter U.S. Experience. Gastrointest Endosc 2016;83:699–707.

191. van Brunschot S, van Grinsven J, van Santvoort HC, et al. Endoscopic or surgical step-up approach for infected necrotising pancreatitis: A multicentre randomised trial. Lancet 2018;391:51–8.

192. Ng SC, Shi HY, Hamidi N, et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: A systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet 2018;390(10114):2769–78.

193. Kaplan GG. The global burden of IBD: From 2015 to 2025. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;12:720–7.

194. Kotze PG, Underwood FE, Damiao A, et al. Progression of inflammatory bowel diseases throughout Latin America and the Caribbean: A systematic review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;18:304–12.

195. Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, et al. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology 2012;142:46–54.

196. Kaplan GG, Ng SC. Understanding and preventing the global increase of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2017;152:313–21.e312.

197. Coward S, Clement F, Benchimol EI, et al. Past and future burden of inflammatory bowel diseases based on modeling of population-based data. Gastroenterology 2019;156:1345–53.e1344.

198. Jones GR, Lyons M, Plevris N, et al. IBD prevalence in Lothian, Scotland, derived by capture-recapture methodology. Gut 2019;68(11):1953–60.

199. Nguyen GC, Targownik LE, Singh H, et al. The impact of inflammatory bowel disease in Canada 2018: IBD in seniors. J Can Assoc Gastroenterol 2019;2(Suppl 1):S68–S72.

200. Ananthakrishnan AN, Kaplan GG, Ng SC. Changing global epidemiology of inflammatory bowel diseases: Sustaining health care delivery into the 21st century. Clin GastroenterolHepatol 2020;18(6): 1252–60.

201. Williet N, Sandborn WJ, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Patient-reported outcomes as primary end points in clinical trials of inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;12:1246–56.e1246.

202. Colombel JF, Panaccione R, Bossuyt P, et al. Effect of tight control management on crohn’s disease (CALM): A multicentre, randomised, controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2018;390:2779–89.

203. Borg-Bartolo SP, Boyapati RK, Satsangi J, et al. Precision medicine in inflammatory bowel disease: Concept, progress and challenges. F1000Res 2020;9:F1000 Faculty Rev-54. Published online 2020 Jan 28 (doi: 10.12688/f1000research.20928.1).

204. Lichtenstein GR, Loftus EV, Isaacs KL, et al. ACG clinical guideline: Management of crohn’s disease in adults. Am J Gastroenterol 2018;113: 481–517.

205. Rubin DT, Ananthakrishnan AN, Siegel CA, et al. ACG clinical guideline: Ulcerative colitis in adults. Am J Gastroenterol 2019;114: 384–413.

206. Wong U, Cross RK. Primary and secondary nonresponse to infliximab: Mechanisms and countermeasures. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 2017;13:1039–46.

207. Na SY, Moon W. Perspectives on current and novel treatments for inflammatory bowel disease. Gut Liver 2019;13:604–16.

原文链接:https://journals.lww.com/ajg/Fulltext/2020/07000/Major_Trends_in_Gastroenterology_and_Hepatology.12.aspx

作者|J.S. Bajaj, D.M. Brenner 等

编译|赵婧

审校|617

编辑|笑咲